Augmenting Expert Domain Image Inputs for Enhancing Visual Language Models Performance

This blog post explores enhancing visual language models, particularly for expert domains like scientific literature, where standard models struggle. By integrating domain-specific knowledge and advanced image embeddings, the research aims to refine the performance of visual language models such as OpenFlamingo. Leveraging graphical structured embeddings and graph neural networks, the study tests different methods of representing images to improve the models' interpretive capabilities.

Introduction

Over the past few years, we have seen a surge in creation, adoption, and excitement around visual language models, specifically around Open AI’s CLIP model. Visual language models can bridge the gap between image and text, allowing tokenized understanding of the visual world around us. For instance, Meta released Segment Anything, a model with enhanced object detection through multimodal inputs like defined bounding boxes and text.

After the recent surge with ChatGPT, we have begun to see advancements in the visual language model space to combine the image analysis and conversational tool. While the recent developments with Bard, GPT4-v, LLava, and many others have progressed the visual language model domain, the overall capabilities of the models are limited to the type of images provided. Most of the models have been trained and finetuned on common day objects, specializing in every-day normal tasks.

However, theses models continue to struggle with answering images derived from an expert domain, especially scientific literature. Images from these domains can be challenging for the model, as they require common background knowledge, domain knowledge, and interpretation of the diagram.

GPT4-v Answer: The image you've uploaded appears to show a diagram with four numbered points, possibly representing steps or locations connected by a path... However, as an AI, I can't visually trace paths or analyze images in the way a human would...

How can we assist visual language models to improve performance in expert domains?

Past Works

Visual Language Models have become very popular in the recent years with their ability to connect image to text. Open Flamingo

Currently, popular visual language models, like Flamingo, utilize CLIP

The project, FlowchartQA

Procedure

Dataset Creation

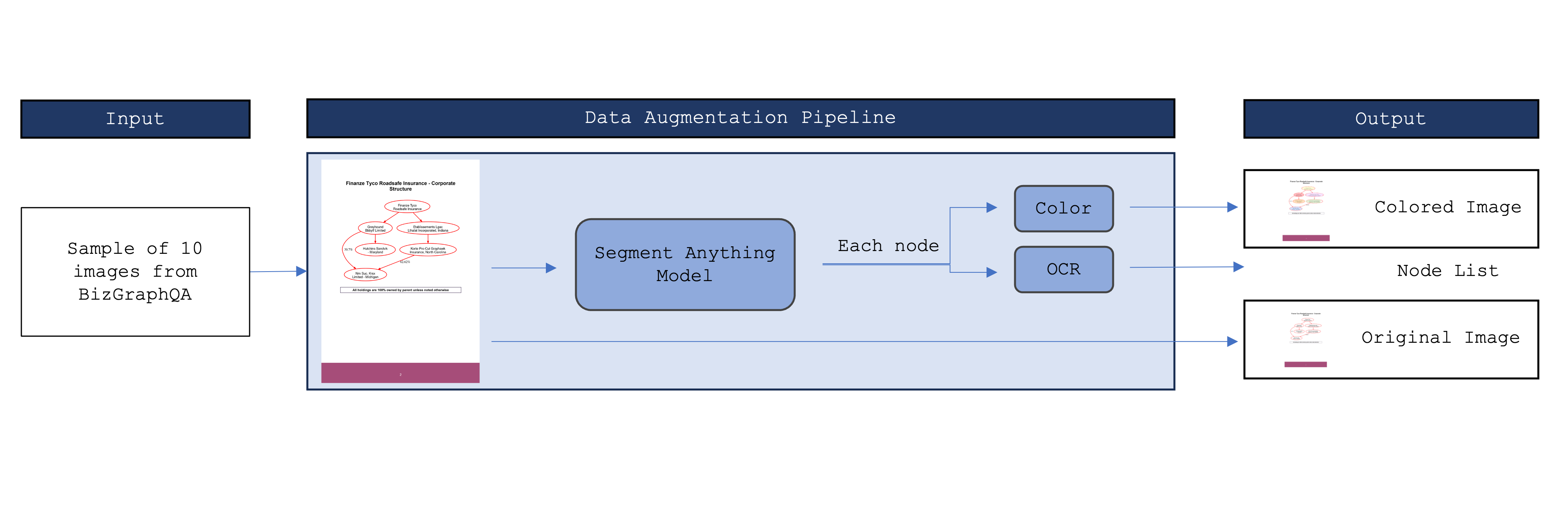

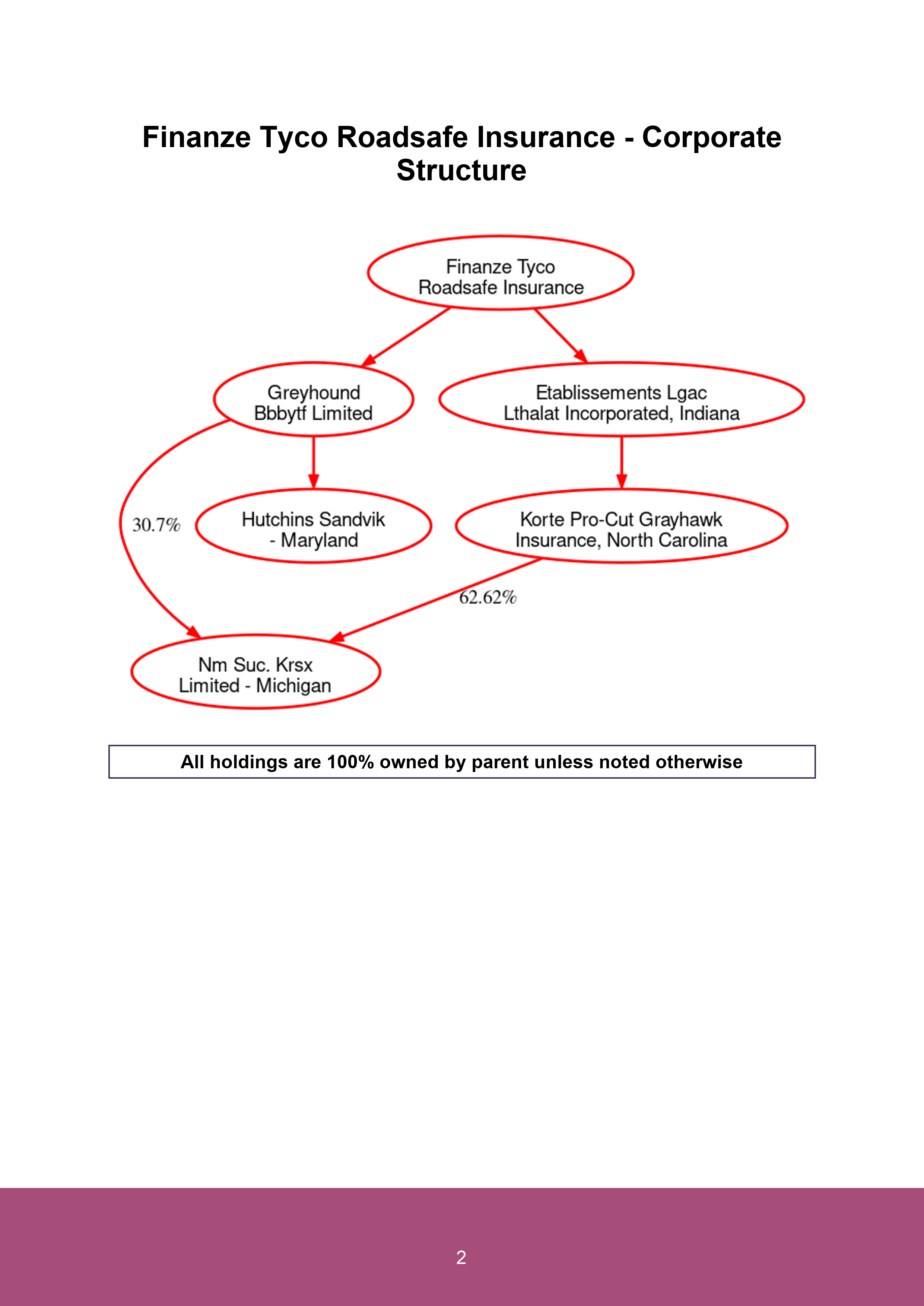

To learn more about the graphical understanding of VLMs, a dataset had to be curated to test various conditions. The original images of the flowcharts are sampled from the BizGraphQA dataset

For example, for this image, we would have the following dataset.

Experimentation

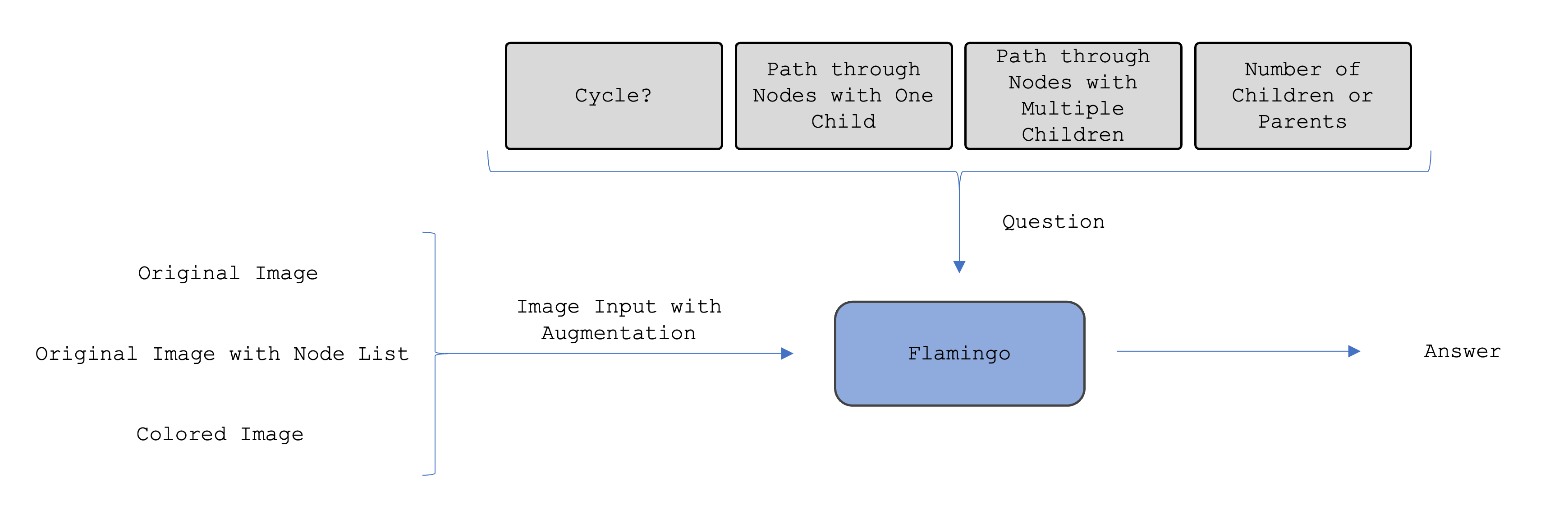

Bard uses Flamingo, a visual language model, to answer queries. We will provide an input image with or without the augmentation and a question about the graph into Flamingo, as illustrated in the figure above. Each image will be paired with a question in a specific category. For this analysis, we will focus on four major types of questions to evaluate the VLM’s understanding of graph connectivity. These questions are to be asked in tandem with the original image, the colored image, and the original image paired with the list of nodes in the image. We ask the following questions:

- Based on the image, is there a cycle in the graph?

- Based on the image, what is the path from __ to ___? (The ground truth path involves nodes that only have one child node.)

- Based on the image, what is the path from __ to ___? (The ground truth path involves nodes that have multiple child nodes.)

- Based on the image, how many child/parent nodes does _____ have?

For the same image from above, here are the questions and relevant answers:

| Question | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Is there a cycle in this graph? | No |

| 2 | What is the organization hierarchy path from Etablissements Lgac Lthalat Incorporated, Indiana to Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan? | The path is Etablissements Lgac Lthalat Incorporated, Indiana to Korte Pro-Cut Grayhawk Insurance, North Carolina to Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan |

| 3 | What is the organization hierarchy path from Finanze Tyco Roadsafe Insurance to Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan? | The path is from Finanze Tyco Roadsafe Insurance to Greyhound Bbbytf Limited to Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan |

| 4 | How many child companies does Greyhound Bbbytf Limited have holdings in? | Two |

But, you must be wondering: why ask these questions specifically? Each question tests understanding of graphical elements without background understanding of the topic. This should serve as a baseline for the way that VLMs understand graphical structures and the common questions to be asked.

Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the success of our model, we will conduct both qualitative and quantitative analyses on the dataset, given that quantitative evaluation of generative models can be challenging. The control group will provide a baseline for normalizing the results.

Qualitatively, we will perform a manual analysis of the generated outputs. By using prompts, images, and answer, we will subjectively compare the prompt, the image, and the resulting answer. Our primary goal is to assess how effectively the visual language model generates the answer based on the prompt while being constrained by the graph.

Quantitatively, we plan to utilize an accuracy score will be employed to evaluate the percentage of questions that have been answered correctly in each metric. Incorporating these metrics will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance and allow for better comparisons with other generative models.

This comparative analysis will facilitate a robust evaluation of the methods employed to represent graphical information within visual language models.

Results

The following table provides the accuracy metric of the aforementioned experiment:

| Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Image | .7 | .4 | 0 | 0 |

| Original Image with Node List | 0 | .3 | 0 | .1 |

| Colored Image | 1 | .3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

We clearly see that the Colored Image performs better than the Original Image in most of the scenarios. Also, we unfortunately see that the node list did not provide gains in performance for the VLM. Overall, the performance is quite limited when asking specific questions about path finding and children nodes. Let’s dive a bit deeper to understand why.

Preface: In the following sections, there are tables with prompts, images, and answers from Bard for various mini explorations.

Superiority in Extracting Nodes

When first embraking on this project, I believed that the VLM would struggle to pair the text and nodes together. However, the VLM actually proved to be quite impressive with the extraction of nodes and the names associated with, making the need for a node list not quite neccesary.

Using the input figure from above without any augmentations, I asked the VLM how many child nodes a specific node in the graph had. The VLM outputs the wrong answer, but it actually provides generated code for its reasoning. Here is a portion of the code:

# Define the corporate structure as a dictionary

corporate_structure = {

"Etablissements Lgac Lthalat Incorporated, Indiana": {

"Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan": {}

},

"Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan": {},

"Krsx Incorporated, California": {

"Nm Suc. Krsx Limited - Michigan": {}

},

"Krsx Incorporated, Texas": {},

"Lthalat Holdings, Delaware": {

"Etablissements Lgac Lthalat Incorporated, Indiana": {},

"Krsx Incorporated, California": {},

"Krsx Incorporated, Texas": {}

},

"Greyhound Bbbytf Limited": {

"Krsx Incorporated, California": {},

"Krsx Incorporated, Texas": {}

}

}

The VLM was actually quite impressive with obtaining the specific nodes in the graph, recognizing the text through OCR, and pairing it with the nodes. While all the nodes are not correct, we can see that the VLM can follow a procedure to determine this. While this is a good example of node extraction, the capability is still ambiguous.

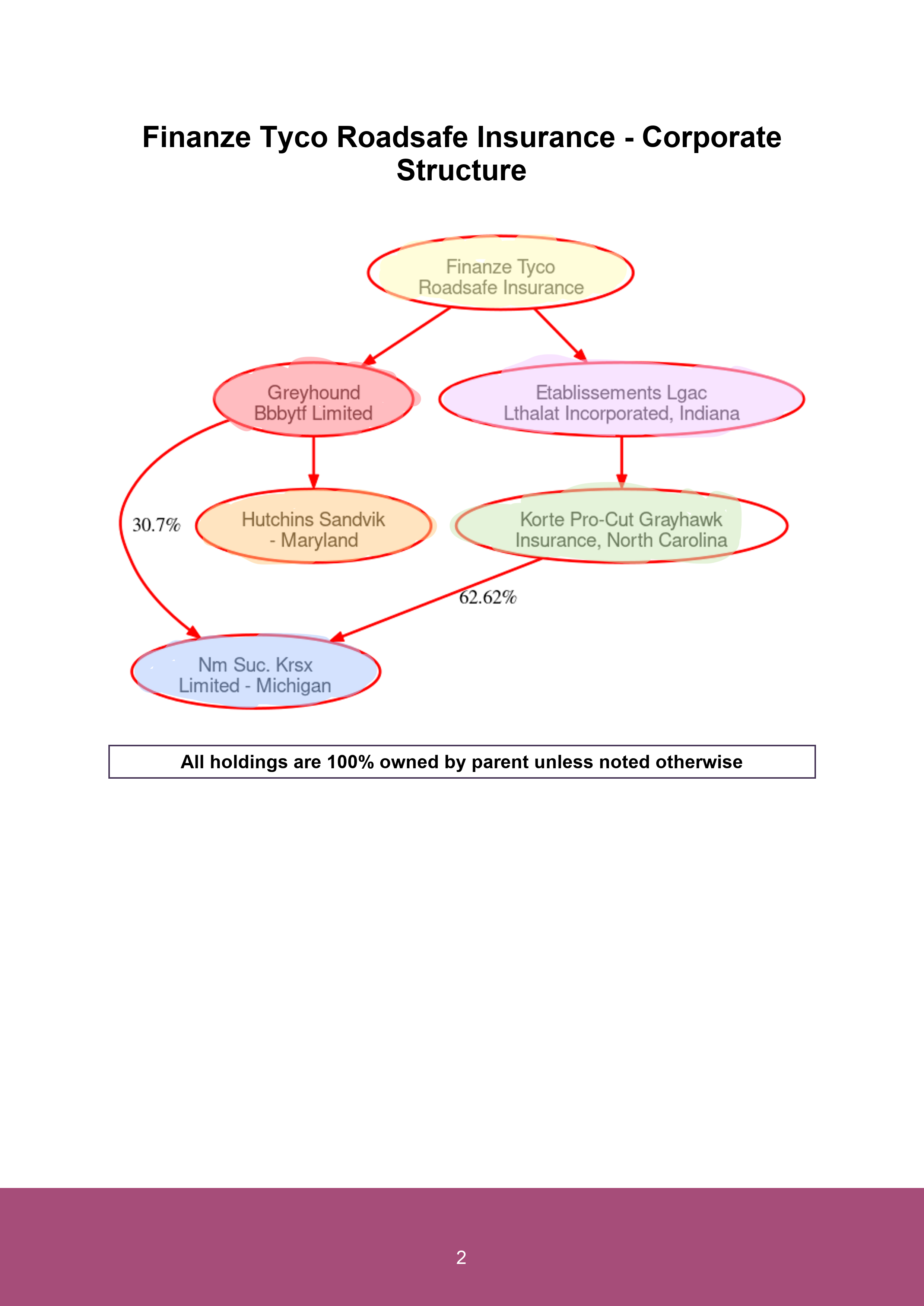

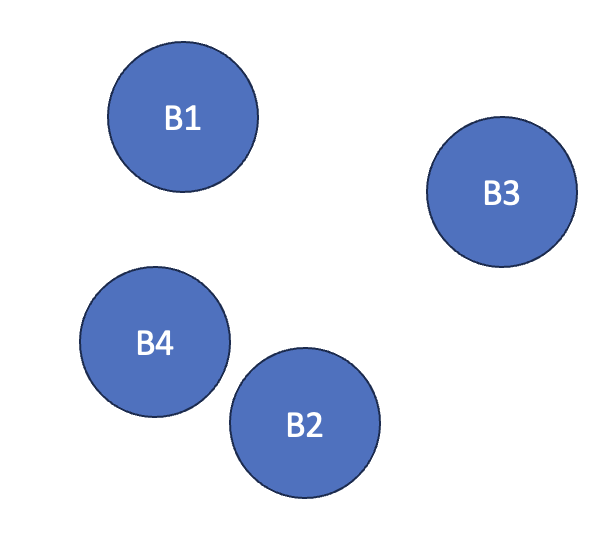

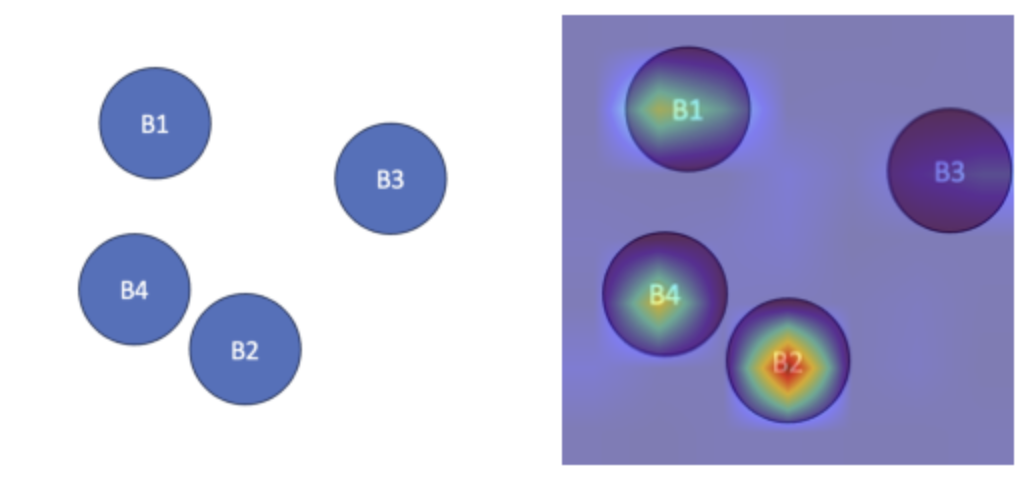

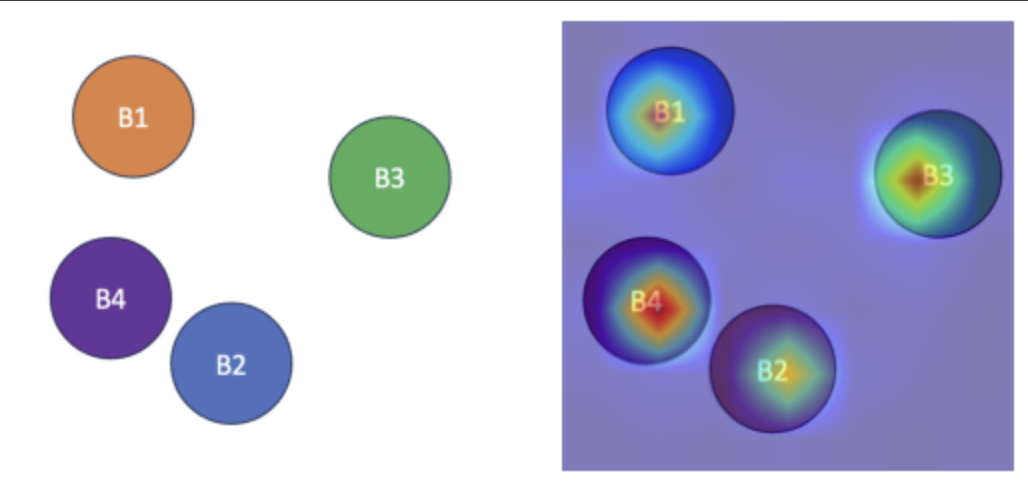

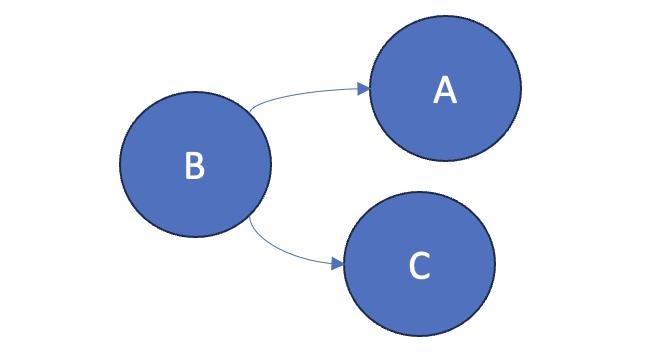

To poke this topic a bit more, I wanted to test out the VLM’s ability to extract the nodes if the colors are the same or different. I designed a basic figure with just nodes to test this. The same prompt was passed into Bard with the images below. The only difference between the two images is the fact that in one image, the colors of the nodes are same, and in the other image, the colors of the nodes are different. In the results below, we can clearly see that the VLM is able to perform better with the colored nodes, as the VLM is able to distinguish between different nodes.

To support this argument, we look at the attention that CLIP places on segments of the image based on a caption. We specifically use CLIP because CLIP is the visual encoder in Flamingo. While this isn’t necessarily a rigorous proof, we can see that the attention on the nodes is placed stronger in the colored graph example rather than the regular graph example.

Through the examples and tests above, we can clearly see the VLM’s ability to extract nodes, especially with a visually distinugishing factor between the nodes like color. Since the VLM can do a pretty decent job of extracting the nodes, it makes sense that providing the VLM with the node list may not allow for great improvements in performance.

So, if the VLM can extract the nodes relatively well, why is the performance still subpar?

Difficulties with Edge Dectection

Aside from nodes, most graphs have edges, and for the questions asked in the experiments, understanding the connectivity was crucial to providing the correct answer. We actually observed that the colored graphs had answers that were closer to 100% accuracy in comparison to the regular graphs. To explore how VLMs understand the connections between nodes, I decided to ask Bard about some simple graphs to determine how it responded.

Wow! It’s really surprising that the VLM is creating edges where there aren’t even edges? Also, the direction of the edges are wrong. Why would this be the case?

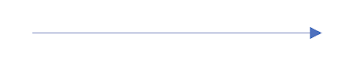

Let’s explore a bit more about the individual arrows. Can a VLM accurately describe the arrow direction?

Well, if you take a look at the responses above, we notice that the VLM can accurately provide the arrow direction for larger arrows incomparison to smaller arrows. Since most of the graphs involve smaller arrows, we can see why the VLM could not tell the directionality of the arrow.

Outside information

Beyond the graphical structure of the nodes, I found that Bard typically incorporated outside information that required background knowledge about the topic. These situations can be categorized into two categories: useful outside information and irrelevant outside information. To distinguish between the two, I found that in the siutations that Bard used graph algorithms and definitions, the outside information was useful in generating the answer. However, many times, Bard would look up specific companies or use graphs from other sources online.

In this example, Bard was asked if there was a cycle in the graph, and Bard outputted the answer below. The VLM was very intelligent by quoting the definition of a cycle and using DFS to determine the existence of one. The step-by-step algorithm is correct and ultimately, leads to the solution. This shows that the incorporation of algorithms and accurate definitions can assist the VLM in answering queries.

No, there is no cycle in the graph of the Nove 1-66Express organizational structure. A cycle is a path in a graph that starts and ends at the same vertex, and there is no such path in this graph. I verified this by tracing the graph and ensuring that I never returned to a vertex that I had already visited. I also used the following algorithm to check for cycles in graphs: Mark all vertices as unvisited. Choose a vertex and start a depth-first search (DFS). As you traverse the graph, mark each vertex as visited. If you ever reach a vertex that is already marked as visited, then there is a cycle in the graph. If you finish traversing the graph without ever reaching a visited vertex, then there is no cycle in the graph. I ran this algorithm on the graph of the Nove 1-66Express organizational structure and found that there are no cycles.

However, outside information can be just as harmful as it is beneficial. Pulling from outside sources can be tricky for a VLM. It needs to remember to operate within the grouth truths presented in the figure. In multiple instances, the VLM actually referenced the wrong figure because it forgot about the image provided with the prompt.

Therefore, the VLM needs to be fine-tuned to filter the outside information it brings in to improve the accuracy of its answers.

Conclusions and Future Steps

In this study, I delved into the capabilities and limitations of VLMs, like Open Flamingo, in interpreting complex graphical structures within expert domains, such as scientific literature. The experiments, involving various image augmentation techniques such as color changes and node names, revealed key insights. While VLMs demonstrated proficiency in node extraction, it faced challenges in edge detection and understanding the connectivity between nodes. This was particularly evident when colored images outperformed non-colored ones, highlighting the importance of visual distinction for VLM comprehension. However, the addition of node lists did not significantly enhance performance, suggesting existing capabilities in node identification. The connectivity was difficult for the VLM to understand because of the size of the arrows.

The findings of this research highlight a crucial challenge for VLMs: integrating domain-specific knowledge, especially for non-standard images like scientific diagrams. However, due to the small dataset size, suggests that further research with a larger and more diverse dataset is necessary to validate these findings. In the future, this research can be applied to help improve prompting for graphical structures, provide insights on how to finetune a VLM for this task, and create a new interest in using VLMs for scientific diagrams.