Unraveling Social Reasoning in LLMs: A Deep Dive into the Social IQA Benchmark

In this study, we investigate the challenge of social commonsense reasoning in large language models (LLMs), aiming to understand and categorize common errors LLMs make in social commonsense reasoning tasks.

Unraveling Social Reasoning in LLMs: A Decision Tree Framework for Error Categorization

Introduction

Social commonsense reasoning is a skill most people acquire within the first few years of life, often without formal education. Consider this example of a social commonsense reasoning question:

Q: Kai was frantically running to a gate at the airport. Why was Kai running?

A) They were trying to catch a flight that departs soon

B) They were training for a marathon

C) They were testing out their new running shoe

Most would likely infer that Kai was rushing to catch a flight that would depart soon and choose A, the correct answer. Social commonsense reasoning, at its core, entails reasoning about the past, current, and future states of others.

Despite advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs), prompting models to achieve near-human levels of performance in different tasks across various domains, they have traditionally struggled with social commonsense reasoning tasks, often underperforming humans. Though, this isn’t surprising to most observers

To better understand why, previous studies have created benchmarks for social commonsense reasoning

Specifically, our blog investigates the question, What are underlying themes in social errors that large language models make? From both a qualitative and quantitative perspective. The goal of our findings is to help discover if there are methods that could potentially address these errors.

To answer this question, we ran Flan-T5 on the Social IQA benchmark, which was introduced in 2019 and features 38,000 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) designed to gauge “emotional and social intelligence in everyday situations”

Upon making this curious realization, we pivoted our project from designing a decision tree abstraction for providing detailed categorization of social commonsense questions to analyzing and addressing the two types of errors:

Type 1: Errors stemming from the flawed construction of the Social IQA dataset

Type 2: Errors where Flan-T5’s choices don’t align with social commonsense.

In the first error group, even reasonable humans, including this blog post’s authors, disagreed with Social IQA’s “correct” answers. Questions in this first group have nonsensical contexts/questions, lack a single reasonable answer, or have many reasonable answers.

When examining questions in the second error group, we noticed that Flan-T5 often over-infers underlying reasons when a more straightforward answer exists. To address this group of errors, we visualized T5’s attention mechanisms when processing such questions.

Background and Related Works

LLMs and Reasoning

Language models like GPT-4 have captured widespread media attention, given their question-answering capabilities.

Throughout the development and testing of LLMs, various tasks have been developed to empirically assess these models’ abilities and limitations. In literature, these tasks are typically categorized into two main groups: natural language understanding (NLU) and natural language generation (NLG). NLU tasks evaluate a language model’s ability to understand natural language. This includes tasks like Natural Language Inference, Reading Comprehension, and various reasoning tasks, including social commonsense reasoning

Comprehensive Overview of Social Commonsense Reasoning Benchmarks

Over 100 large-scale benchmarks have been proposed to assess and compare models’ social commonsense reasoning abilities and to serve as resources for transfer learning

Notable benchmarks frequently mentioned in the literature include multiple-choice Question Answering (QA) benchmarks like the 2019 Social IQA

Similar to that of other studies evaluating LLMs’ commonsense knowledge, we use an MCQ benchmark and not a generative one because they are more simple and reliable for evaluation

However, despite their widespread use, benchmarking datasets like Social IQA are not without flaws. Previous studies have shown that many aspects of common sense are still untested by these benchmarks, indicating an ongoing need for reliable methods to evaluate social commonsense reasoning

Problems With Social IQA

Social IQA focuses on evaluating models’ abilities to reason about others’ mental states, aligning with Theory of Mind concepts

In the first two phase, MTurk crowdsource workers sourced context sentences and questions using the ATOMIC knowledge base

Many critiques have been raised about the reliance on crowdsourcing for benchmarks, specifically, about the challenges in obtaining high-quality material

Prior Error Analysis Work Using Social IQA Dataset

The authors of Social IQA conducted a preliminary error analysis of their dataset, finding that language models found questions about context pre-conditions, such as motivations and prior actions, to be much easier than those about stative attributes or predicting future actions. Interpreting these results, the authors hypothesized that models might be learning lexical associations rather than true meaning

Other research, such as Wang et al.’s

General Methodology for Conducting Systematic Error Analysis for QA

Our research, aimed at identifying themes in social errors made by LLMs, draws inspiration from conventional methodologies for system error analysis in QA tasks. Moldovan et al.’s data-driven approach to QA error analysis, focusing on answer accuracy based on question stems, reveals that certain question types are more challenging for LLMs

Existing Approaches to Improve Social Commonsense Reasoning

Our research also explores existing literature offering solutions for mitigating errors in social commonsense reasoning. Some of these works suggest incorporating external structured data, such as knowledge graphs, into models. For example, Chang et al. showed that integrating knowledge graphs like ConceptNet improves performance on Social IQA

However, despite confirming the effectiveness of this approach, studies like Mitra et al. also noted instances where models, even with access to relevant information that can directly lead to the correct answer, predicted incorrect answers based on irrelevant knowledge

Methodology

Step 1: Applying Flan-T5 to Social IQA

We first prompted Flan-T5, known for its promising reasoning task performance

[Context].

Based on the context above, choose the best answer to the question:

[Question]

OPTIONS:

(A) [Answer A]

(B) [Answer B]

(C) [Answer C]

For your answer, return exactly one character, either A, B, or C.

Step 2: Qualitative Coding of 350 Errors

Next, we used the following procedure, based on standard iterative qualitative coding methods, to categorize instances where Flan-T5’s response differed from the Social IQA dataset’s correct answer.

-

Initial Annotation: initially, for a subset of 100 rows, two independent coders annotated each row, noting the reasons for the discrepancy in the correct answer choice between the dataset and Flan-T5.

-

Theme Identification: the coders reviewed each other’s annotations and engaged in discussions to identify major themes in inconsistencies. Based on these discussions, they developed a formal set of tags to apply to the rows.

-

Tagging: finally, they applied these tags to a total of 350 rows

Step 3: Quantitative Error Analysis

We then analyzed the data to determine the frequency of each error type within our tagged dataset (n=350). We explored potential features, such as specific words, that contributed to the difficulty of the questions.

Step 4: Addressing Type 1 Errors - Developing a Pruning Tool

Our objective here was to develop a tool that could use our tagged question set to accurately identify problematic questions. Unfortunately, this approach did not yield the desired results and needs future work.

Step 5: Addressing Type 2 Errors - Analyzing through Attention Mechanism Visualization

Finally, we shifted our focus to examining errors by visualizing the attention mechanisms of the model. This approach aimed to provide deeper insights into how the model processes and responds to various types of questions, particularly those categorized as Type 2 errors.

Analysis and Evaluations

General Accuracy of Flan-T5 on Social IQA

Overall, Flan-T5 exhibits a high accuracy of 90% when presented with MCQs from Social IQA, which could be because it was fine-tuned “on a large set of varied instructions,” similar to the questions we present it

Set of Formal Tags Derived from Qualitative Coding

In the initial annotation phase of qualitative coding, both coders were surprised to find many questions marked “incorrect” because of issues inherent in the Social IQA questions themselves (see below for an example). Therefore, we wanted to characterize why the Social IQA multiple choice questions were problematic: was it a lack of context comprehension, the unreasonableness of all answer options, or the presence of multiple equally reasonable answers?

During the theme identification phase, the coders established two groups of tags:

-

Errors arising from the flawed construction of the Social IQA dataset

-

Errors due to Flan-T5’s responses not aligning with social commonsense

Type 1 Errors

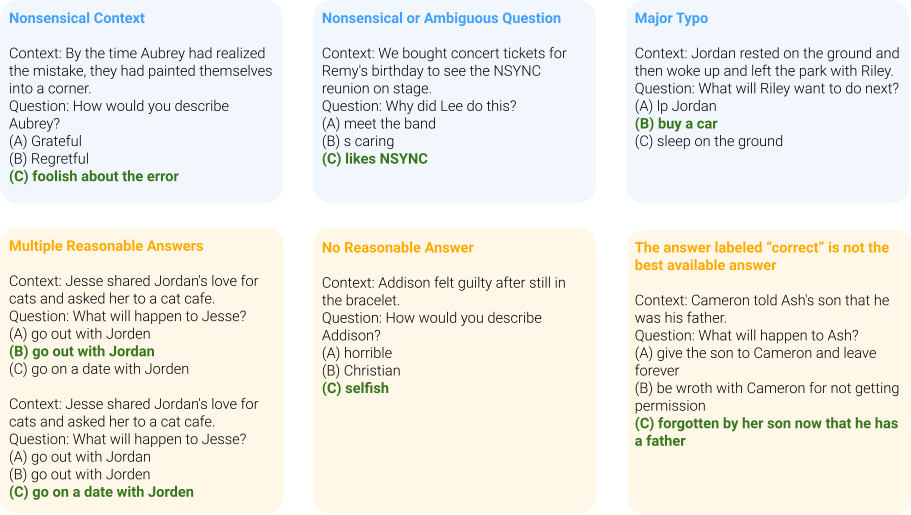

For Type 1 errors, six labels were created:

-

Nonsensical Context: When the context sentence is incomprehensible to a reasonable human.

-

Nonsensical or Ambiguous Question: When the question is either nonsensical or too ambiguous.

-

Major Typo: Refers to incomprehensible parts of the Context, Question, or answer choices due to typos.

-

Multiple Reasonable Answers: When several answers appear equally reasonable, either due to similar meanings or general reasonableness.

-

No Reasonable Answer: When no answer options seem appropriate or reasonable.

-

Incorrectly Labeled “Correct” Answer: When an alternative answer seems more reasonable than the one marked “correct.”

Examples of Type 1 Errors

Type 2 Errors

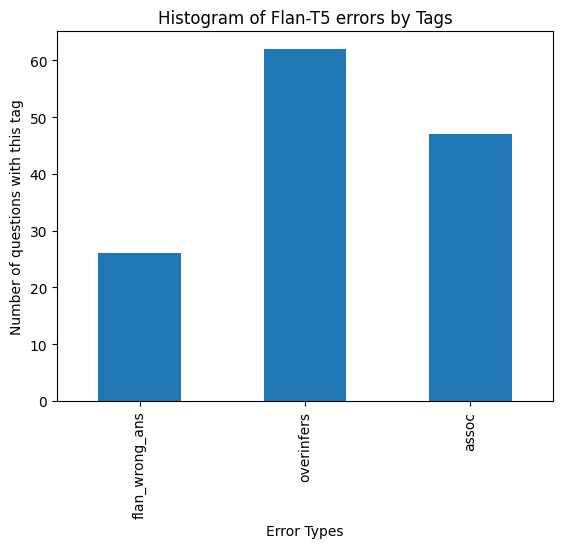

For Type 2 errors: we devise the following set of three labels:

-

Overinfers: This tag is for questions where Flan-T5 seems to make a large leap in logic, resulting in it picking an answer choice that makes spurious assumptions when a much more direct and clear answer is available

-

Associated but Incorrect: This is for questions where Flan-T5 picks an answer choice that is associated with the context and question, but is not what the question is specifically asking about. This differs from over-inferring in that this usually entails picking irrelevant answer choices.

-

Flan-T5 Incorrect (unspecified): all other mistakes attributable to Flan-T5.

Distribution of Tags

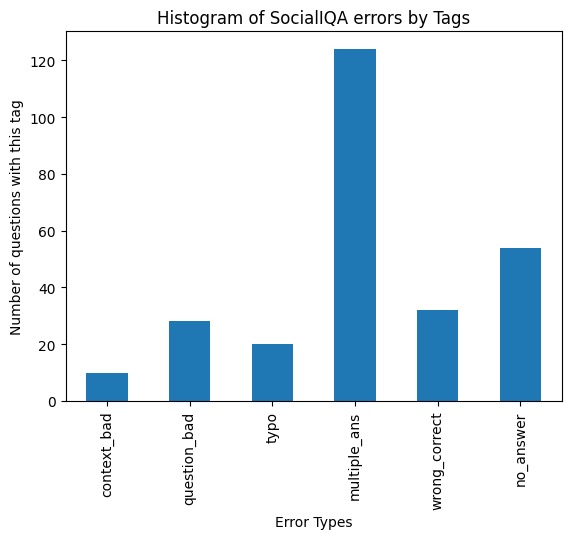

Looking at our annotated questions, we see that 65% of errors stemmed from the flawed construction of the Social IQA dataset. Meanwhile, 38% of errors were errors stemming from Social IQA not picking the right answer. Observe that it is possible for a question to be tagged with both a Type 1 tag and a Type 2 tag.

For Type 1 errors, we see that having multiple reasonable answers is by far the most common reason why a question is problematic. This was followed by having no reasonable answer, and the answer labeled “correct” not being the best available answer. Indeed, the top three reasons why a question is considered problematic all stem from questionable answer choices. This highlights how the construction of the answer choices, and thus Social IQA as a benchmark set, is problematic.

Next, we examine the distribution of Type 2 error tags. We see that the most common reason is Flan-T5 over-inferring.

Analysis of Question Types

In our quantitative analysis, we identified key features contributing to lower accuracy in certain questions. Notably, questions containing the word ‘others’ scored lower in accuracy, with an average of 0.880, compared to the general accuracy score of 0.990. Furthermore, questions featuring repeated answer choices also exhibited a lower accuracy score of 0.818.

Attempt to Prune Social IQA

Assessing models on social commonsense reasoning questions requires clear comprehension and consensus on the appropriateness of the questions and their answer choices. Our goal was to create a tool to classify the sensibility of these questions and answers. To achieve this, we experimented with various models, including Flan-T5 and GPT-4, asking them to evaluate the coherence of the questions. Unfortunately, the results were inconsistent, often varying with each regeneration of the response. Despite these challenges, we maintain that addressing this issue remains crucial.

Visualization of Attention Mechanism

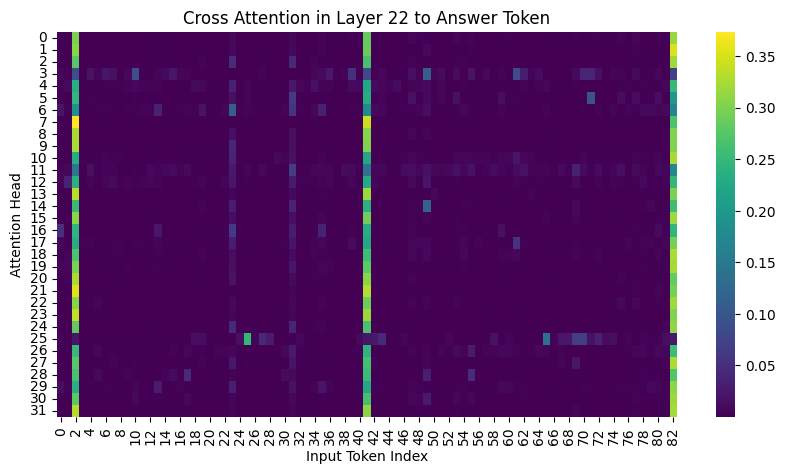

In our analysis of Type 2 errors, we focused on how the errors happen because Flan-T5 overinfers the underlying reasons not explicitly stated in the question instead of picking the more straightforward and correct answer, or picks some answer associated with the words in the context that isn’t directly related to the question.

In addition to providing qualitative analysis, we set out to provide some quantitative analysis to better understand why this was happening. Consider these linked notebooks, which visualize the cross attention and the encoder attention for one correctly labeled example and one incorrectly labeled example, where Flan-T5 chooses an associated but incorrect answer. (Note that the specific images were chosen for brightness in the heatmaps, since the attention was normalized. Please reference the notebook.).

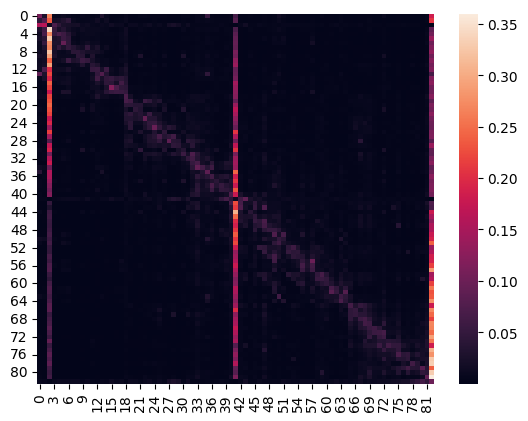

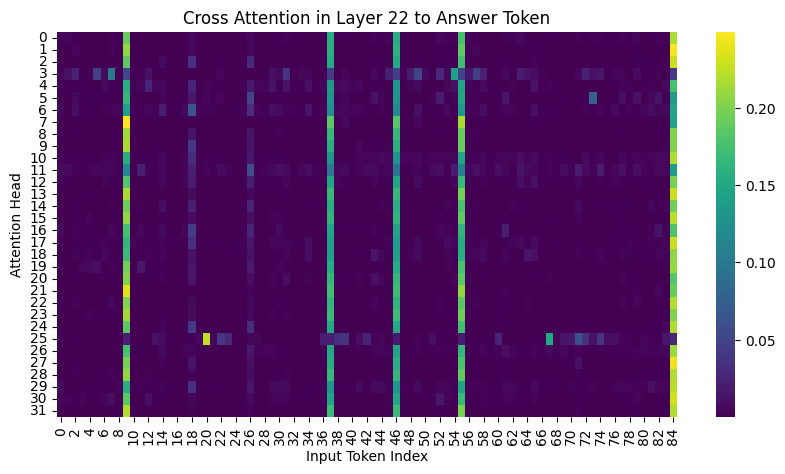

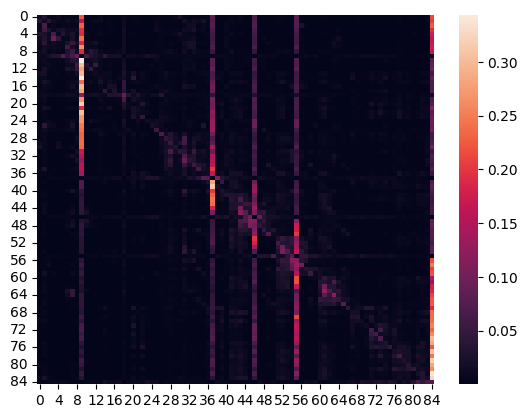

To visualize cross-attention, we looked at the cross-attention between the answer Flan-T5 generates and the encodings, across each layer and attention head in Flan-T5, grouping in both orders. To visualize the encoder attention, we looked at the average attention for each layer in the input encoding, and for the layer that saw the most drastic change (layer 2, starting from 0 index), we visualized the attention for each attention head.

Now, consider the context and question:

Cameron had a big paper due later in the week, so Cameron put pen to paper. What will Cameron want to do next?

A) research his topic

B) write an outline

C) redo his topic

Flan-T5 answers A), while the correct answer is “write an outline.” Notably, Flan-T5 doesn’t choose the third answer, “redo his topic.”

Therefore, we can see that Flan-T5’s is associated with the topic, but isn’t the correct answer, which is given by the phrase “put pen to paper.” Visualizing the average encoder attention and cross attention, we see that the contextualized embeddings and generation primarily focus on the words “big paper” and the question, but don’t pay much attention to the word “pen.”

Generalizing our results a bit, we find that FLAN only pays reasonable attention (normalized attention > 0.05) to the keywords for 14 out of 26 examples tagged under “associated,” even for simpler questions such as

On the other hand, consider the question,

Sydney played basketball with her friends after school on a sunny afternoon. What does Sydney need to do before this?

A) take a nap before this

B) have a basketball before this

C) go home before this

Flan-T5 correctly answers “have a basketball before this,” not choosing “take a nap before this” or “go home before this.”

Indeed, we see the four vertical lines in the encoder and cross attentions that correspond to key phrases in the sentence. For the questions that Flan-T5 gets correct, it pays attention to the right keywords 9 out of 10 times. Lastly, note that for questions labeled “overinfer,” Flan-T5 pays attention to the right keywords 8 out of 10 times.

Therefore, for more straightforward questions, namely, questions that have one straightforward answer, Flan-T5 can find the right keywords that lead it to the answer (i.e. the correct questions). On the other hand, for more challenging questions that require paying attention to specific keywords and reasoning from the perspective of a character (recall the Sally-Anne Test), Flan-T5 struggles more, with more variance between what it pays attention to and doesn’t (e.g. paper but not pen).

In addition, since Flan-T5 pays attention to the right keywords most of the time for the questions it overinfers on, this suggests that there’s some aspect of reasoning that’s not being captured via our attention visualizations, and that this reasoning isn’t performing that well.

Notably, something interesting to note is that for all of the examples, by the third encoder layer, on average, Flan-T5 doesn’t change its encodings, and for the cross attention, the attention remains consistent across all layers and (most) attention heads. Therefore, it seems like most of the “reasoning” is being performed in the encoding stage.

Therefore, some of our next steps are understanding how removing attention heads in a smaller affects the model’s ability to reason, given the large number of heads and layers (24 x 32) in Flan-T5-xxl . We visualized each encoder head for one layer, but this doesn’t immediately lend itself to an intuitive interpretation.

Discussion

Our work concentrated on analyzing two categories of errors and proposing solutions to address them. The two error types are:

-

Errors originating from the flawed construction of the Social IQA dataset.

-

Errors where Flan-T5’s responses do not align with social commonsense.

Problems with Social IQA

Our analysis of Type 1 errors in the Social IQA dataset revealed significant issues. In examining n=350 incorrectly answered questions, we found that 65% had problems with their context, question, or answer choices. Additionally, 54.4% of these errors had multiple reasonable answers, 23.7% lacked any reasonable answer, and 14.0% seemed to have mislabeled correct answers. This indicates a substantial number of misleading answer choices in the Social IQA questions.

This issue partly stems from the dataset’s construction, which involved assigning crowdsourced workers tasks of writing positive answers for each question and sourcing negative answers from “different but related” questions. This approach likely contributed to the high error rate.

Since Social IQA is so frequently used in evaluating model performances and transfer learning tasks, the challenge is to identify and remove these flawed questions. Although our attempt to do this was unsuccessful due to time and budget constraints, we believe it is feasible. Many evaluations of large language models (LLMs) use crowdsourced multiple-choice questions, so a pruning tool to ensure benchmark reliability would be highly beneficial beyond the task of social commonsense reasoning.

Pruning the Social IQA dataset to eliminate most erroneous questions would also provide an opportunity to reassess older models.

Overall, our analysis of Type 1 errors underscores the need for caution in crowdsourcing benchmark questions. While crowdsourcing likely still remains the best solution for creating large benchmark sets, a pruning tool is essential to maintain the reliability of such datasets.

On the other hand, our analysis of Type 2 errors suggests that LLMs still might not match the social reasoning skills of humans for more complex scenarios. For simpler questions, they can often find a single keyword that informs their answer, while for more complex questions, they often miss important phrases and can’t necessarily think from another person’s perspective. For instance, recall how questions containing the keyword “other” result in Flan-T5 having considerably lower accuracy.

Main Limitations

The primary limitations of our study are rooted in its scope and methodology. Firstly, we focused exclusively on a single model, Flan-T5, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, our analysis was based on a relatively small sample size of n=350, and it involved only two coders. For a more robust and comprehensive evaluation, increasing the number of coders would be beneficial, particularly to assess intercoder reliability. Furthermore, implementing measures to mitigate recognition bias during the tagging process would enhance the validity of our results.