Learning Generals.io

We explore the application of deep learning to the online game generals.io and discuss what is necessary to achieve superhuman performance in generals.io.

Introduction

Generals.io is a real-time turn-based strategy game. In generals.io, two players with a “general”, denoted with a crown, spawn on a board with mountains and cities scattered. Initially, players have no knowledge of other parts of the board besides the tiles immediately surrounding their general. Armies are the main resource of the game, which generate slowly from ordinary tiles, but quickly from the general and cities. Using armies, players compete to capture terrain and cities, which also grants further vision of the board. On each turn, a player is able to click on a cell with their army and use the keyboard to move it in the four cardinal directions. The goal of the game is for the player to use their army to capture the tile of their opponent’s general.

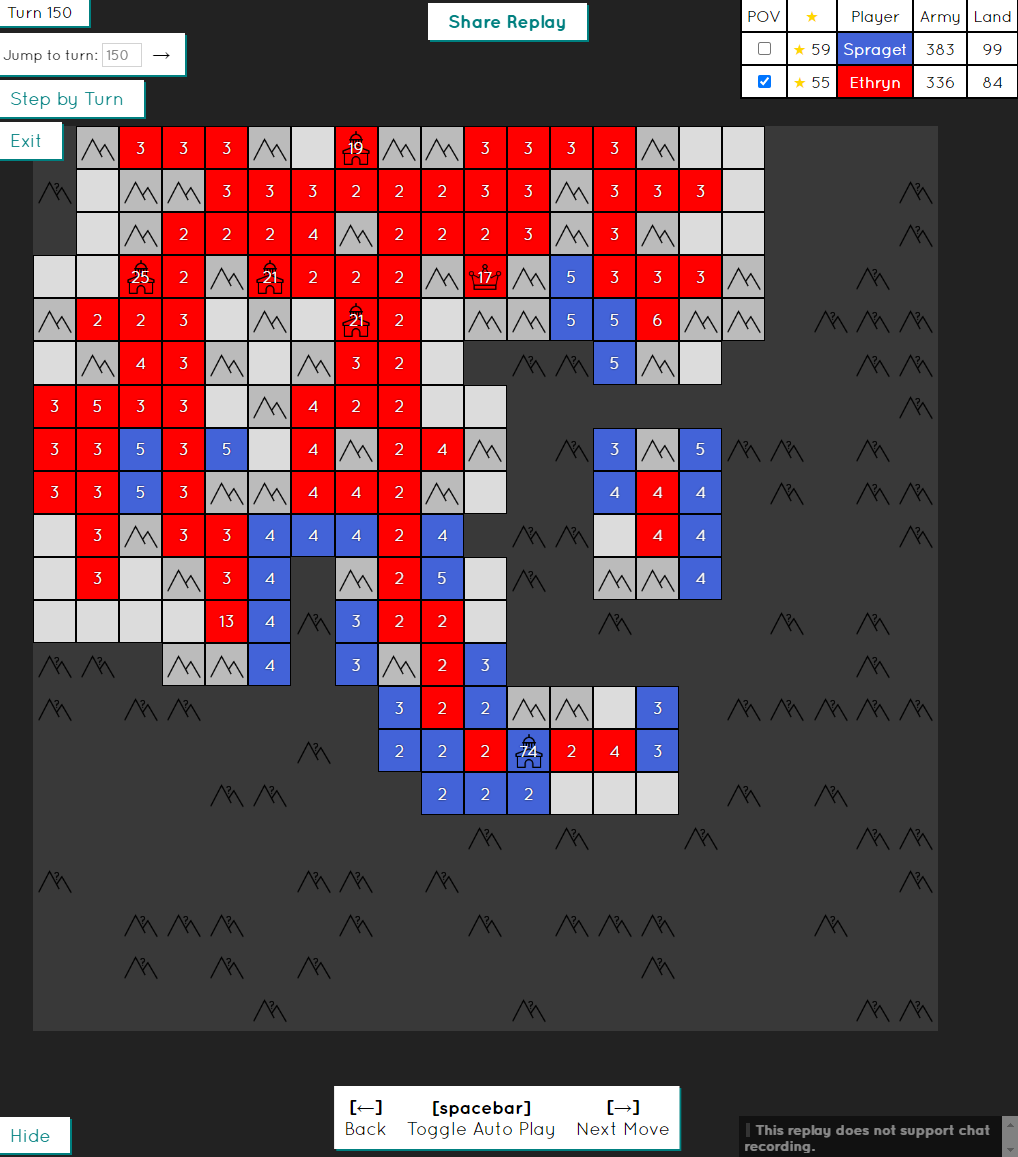

A typical game state will look like the following:

Generals.io has a modest daily player base and has had attempts to implement bots to play against humans. Currently, no bots have been able to defeat top humans consistently. The top bots, such as this one, are implemented using rule-based logic. They achieve human-level performance and are able to win some games against the top 10 ranked players. Previous machine-learning based bots have attempted to use a CNN LSTM in the model architecture, such as this post by Yilun Du. He separately evaluates a supervised learning approach and a reinforcement learning approach. His supervised learning approach reaches a competent level of play and is able to expand while having an awareness of needing to defend. However, it is very inefficient and makes basic strategic mistakes, such as running army into cities without fully taking them. The reinforcement learning approach was trained using A3C from scratch, but it was not able to learn beyond random movements.

I set out to build on Yilun’s work and improve the bot’s performance, as well as explore and document what details are actually important for improvement.

Related Work and Why Generals

Deep learning has already been used to conquer many games, achieving either human-level or superhuman-level performance. The pattern for most games has been to use deep reinforcement learning at enormous scale through self-play. There has been success in chess, Go

While games in higher complexity have already been defeated by deep learning, the experimentation is often quite opaque, as there are too many decisions that are made to be worthy of reporting on. Furthermore, the games and methods are often way too large for a single researcher to reproduce. For example, OpenAI Five was only able to beat Dota 2 pros after training for ten months, using 770 PFlops/s-days. Generals.io allows for more accessible experimentation through its smaller size and open data pipeline for replays.

I think there are still insights to be gained in defeating generals.io. In particular, the game comes with a combination of challenges that aren’t clearly addressed by previous approaches:

- The game is requires a high degree of calculation and precision, as well as strong intuition. Similar to chess, certain parts of the game are more intuitive and positional, and certain parts require searching through possibilities to calculate precisely. In generals.io, the precision mostly comes from being maximally efficient in the opening, as well as calculating distances relative to opponents army. This would suggest that some kind of model needs to search in order to achieve superhuman performance.

- The game is partially observable. This prevents approaches used in perfect information games such as Monte Carlo Tree Search, as we need to form belief states over the opponents state.

- The state and action space is enormous, and it requires planning on long time horizons. Games such as poker satisfy both of the above two bullet points, but it was able to be tackled with approaches such as counterfactual regret minimization after bucketing the state and action space

. Bucketing the state and action space likely won't work for generals.io, nor will an approach like CFR work.

Methods

Formally, generals.io can be represented as a POMDP. The underlying state, which is the state of the whole board, can only be observed at tiles that are adjacent to tiles claimed by the player.

A wealth of data (over 500,000 games, each containing hundreds of state-action pairs) are available via human replays. We use imitation learning to try to learn from the replays. Concretely, the problem can be modeled as selecting parameters \(\theta\) of a policy \(\pi\) (a neural network) to maximize the log likelihood of the dataset \(D\):

\[\max_\theta \sum_{(s,a)\sim D} \log \pi_\theta(a | s)\]I used existing tools in order to convert the replays into a json format that could then be parsed. I then adapted Yilun’s code, which no longer directly works, in order to simulate the replays to construct the dataset. To start, I only used 1000 replays of highly ranked players to construct my dataset.

I started mostly with Yilun’s features, with small modifications:

| Channel | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | friendly army values |

| 1 | enemy army values |

| 2 | boolean indicators for mountains and cities |

| 3 | unclaimed city army values |

| 4 | friendly city army values |

| 5 | enemy city army values |

| 6 | boolean indicator for mountains |

| 7 | boolean indicator for friendly and enemy general (if found) |

| 8 | boolean indicator for fog of war |

| 9 | (turn number % 50)/50 |

The features made a lot of sense to me as a generals player - it’s all the information I use to play. I removed Yilun’s last feature since a new replay standard made it impossible to compute.

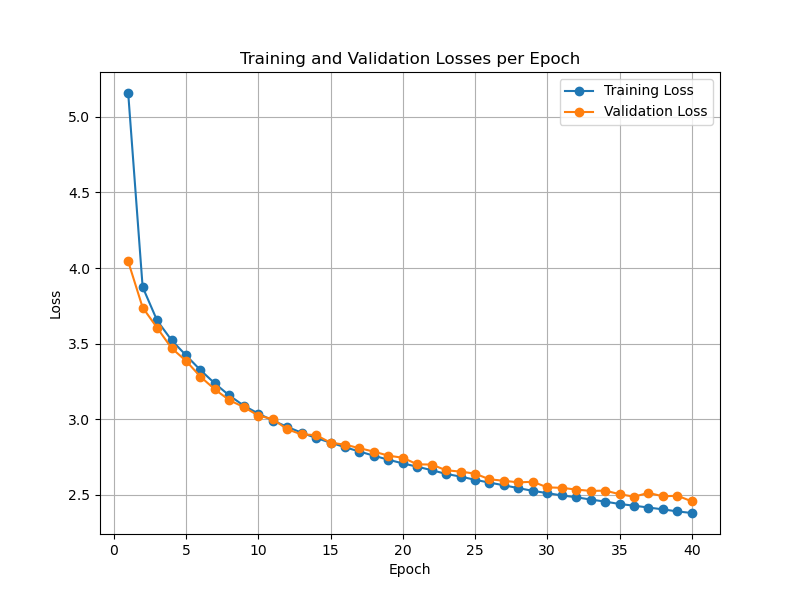

Yilun used a CNN LSTM as his architecture. In order to keep it simple and evaluate the basic components that improve performance, I removed the memory and only used a simple fully convolutional net with 5 stacked 5x5 filters.

Policies were evaluated by coding a small bot in the recently released botting framework for generals. The bot sampled from the policy’s distribution over legal moves. Two policies were able to go head to head through this framework, and I could queue 10 games in order to get good estimates for the relative strength between the bots.

I’ll now describe some of the changes I tried and give an analysis of the results of each change.

Effects of more data

The baseline policy, trained with 1000 games, was not very successful. The bot would often move back and forth, without trying to expand or take land.

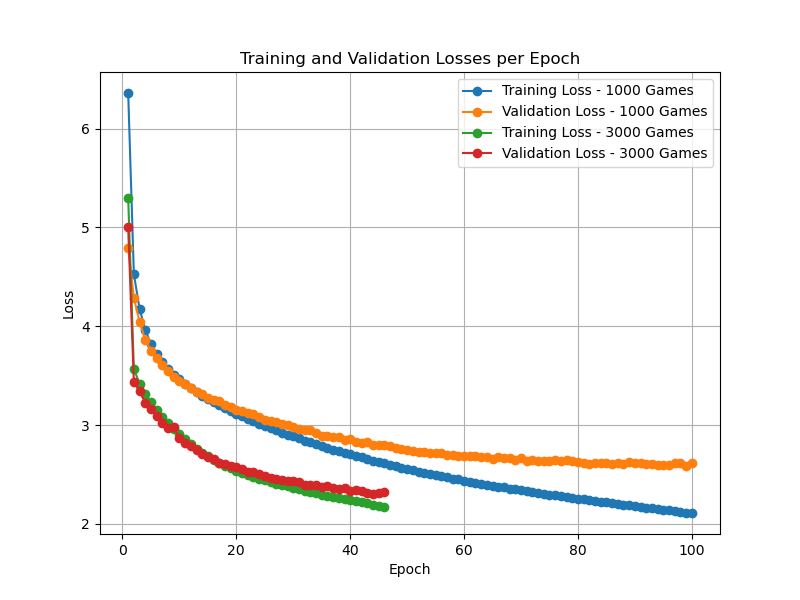

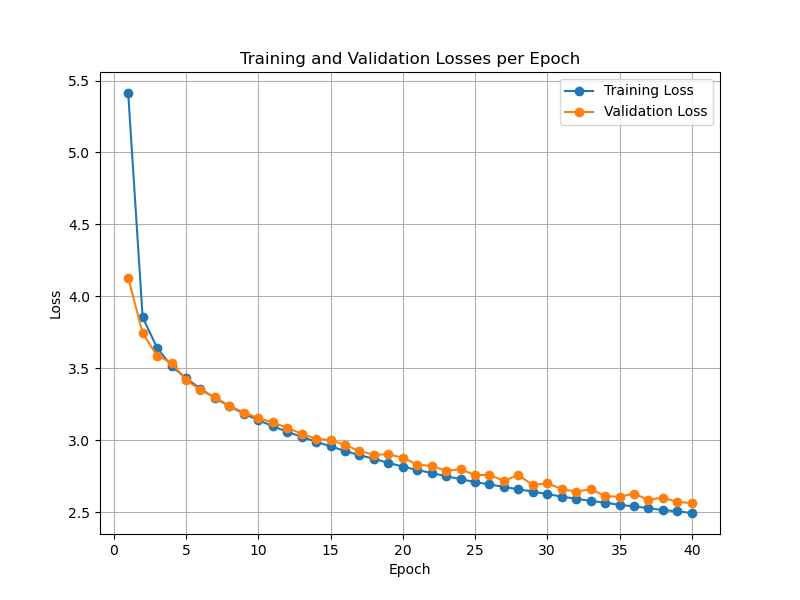

I wanted to first explore how the amount of data affected the policy. I took 2000 more games of high ranking players and trained the same policy on a dataset with 3000 games. I expected an improvement in the similarity of the validation and train loss. This was confirmed by the results, shown below.

This makes sense, as adding more data is essentially a regularizer. It prevents the model from overfitting, as it needs to do well on the added data too. Furthermore, it looks like it converges faster in epoch space, but in reality it’s also going through more examples, so it trained at roughly the same speed if one were to scale the epochs by a factor of 3. The policy was also much more effective, and it did not run back and forth as much. I think this was likely due to reduced overfitting.

I suspect that more data would have improved the policy even more, but I didn’t go larger, as it would have broken past the limits of the infrastructure I built. In particular, the dataset consisting of 3000 games took over 4 GB of disk space. A smarter job of batching the data would have allowed me to train with more.

Squishing army features

Working with the 3000 games, I turned my attention towards improving the features. They were already pretty comprehensive, but I was skeptical of the many army features we had. In particular, all of the other features were binary. Army values ranged from 0 to hundreds. I hypothesized that the features encoding armies could lead to unstable training. Using some knowledge about the game, I thought it would make sense to use a function like a sigmoid, in order to squish large values down.

As a generals.io player, this made sense to me, as the difference between 1 army on a tile and 2 army on a tile is very large, but the difference between 14 and 15 army is not so large. I expected better performance due to the inductive bias I was adding to the model. However, the loss curve showed similar, slightly slower convergence to the previous experiment. The policies were about the same too.

Deeper Network

Motivated by the success of ResNets

Discussion and Conclusion

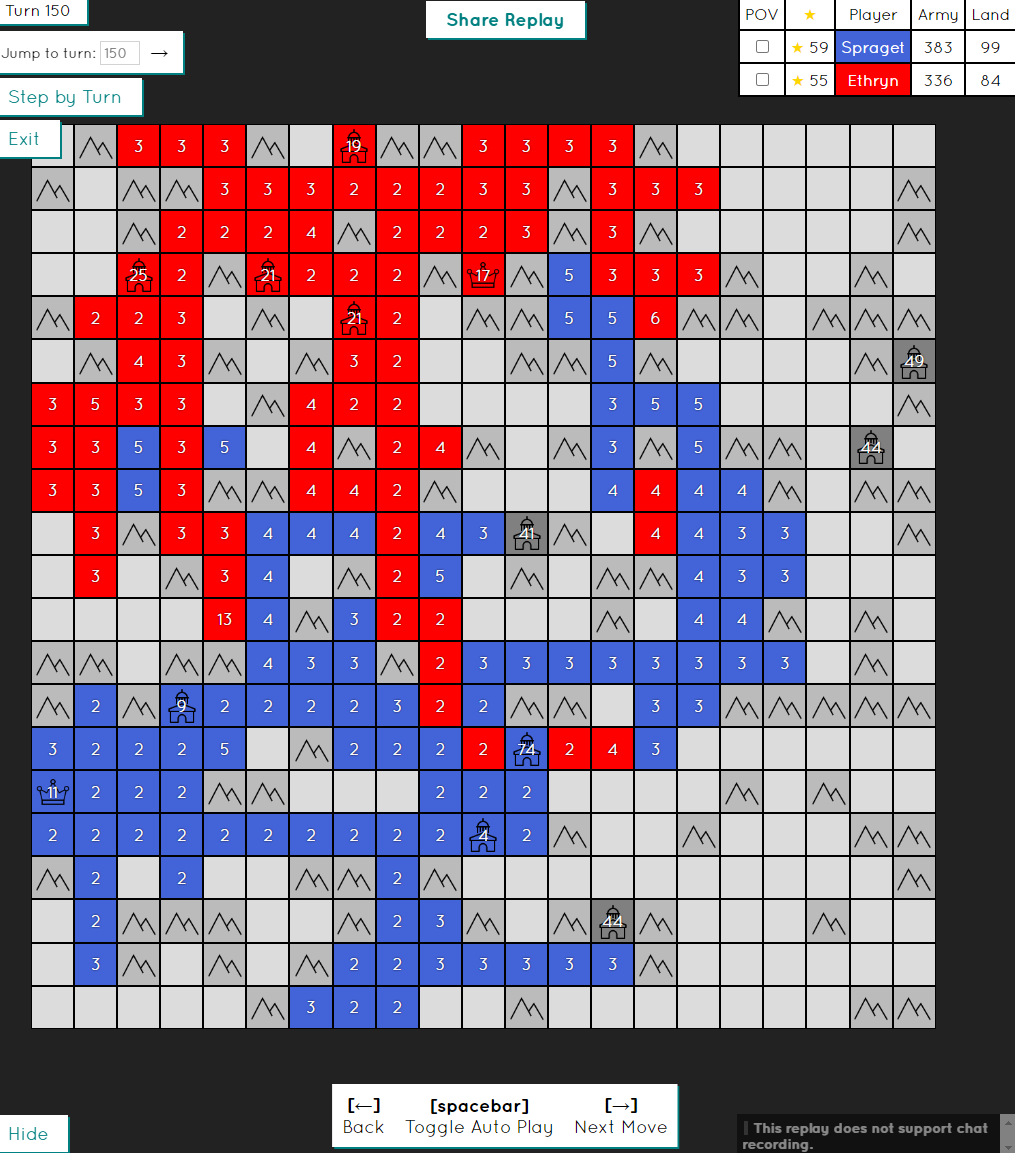

Combining all of the above leads to a decent policy with coherent strategy, shown below.

Qualitatively, this policy is much better than Yilun’s policy. While I don’t have his to evaluate, he shows a replay of its early game performance. My bot does a much better job in the early game of efficiently expanding in order to maximize growth rate. Yilun’s bot has a handle on using a large army to explore, but mine is able to collect army efficiently on turns 25-50 in order to take the opponent’s land.

This is interesting because my policy is actually still much simpler than Yilun’s, given he uses a LSTM. It’s possible that the training was not very stable, or it may have overfit, or he just chose a bad replay of his bot.

Limitations and Future Work

The bot is not competitive with any human that has played a decent amount of games. It is still pretty inefficient and makes many nonsensical moves (it moves back and forth a few times in the replay).

There is still a lot to try, and I’ll actually continue working on some of these ideas after the class, as it was a lot of fun. There’s a decent amount of low hanging fruit:

- I noticed the bots often like to expand toward the wall. I'm guessing this is because there is no information encoding the boundaries of the wall, and I just let the padding in the convolutions take care of it. Adding a special indicator would likely be helpful.

- Use reinforcement learning for improving the policy beyond the demonstrations.

- Train on a dataset consisting of only one or only a few players in order to reduce multimodality problems (similar style of play).

- Adding memory to the network.

- Trying a vision transformer

, and trying to have it attend to previous states for recurrence too.

I think achieving even higher levels of performance would require doing some form of search. From my understanding, the most similar approach would be something like MuZero

Overall, I learned a ton in this project about how to apply deep learning to a new problem. I encountered many of the issues described in “Hacker’s Guide to DL” and the related readings. My biggest takeaway is to spend the time setting up the proper infrastructure. Poor infrastructure causes bugs and makes it really hard to iterate.