Transfer Resistant Model Training

This blog post details our work on training neural networks that are resistant to transfer learning techniques.

Introduction and Motivation

In transfer learning, a model is trained for a specific task and is then fine-tuned for a different task

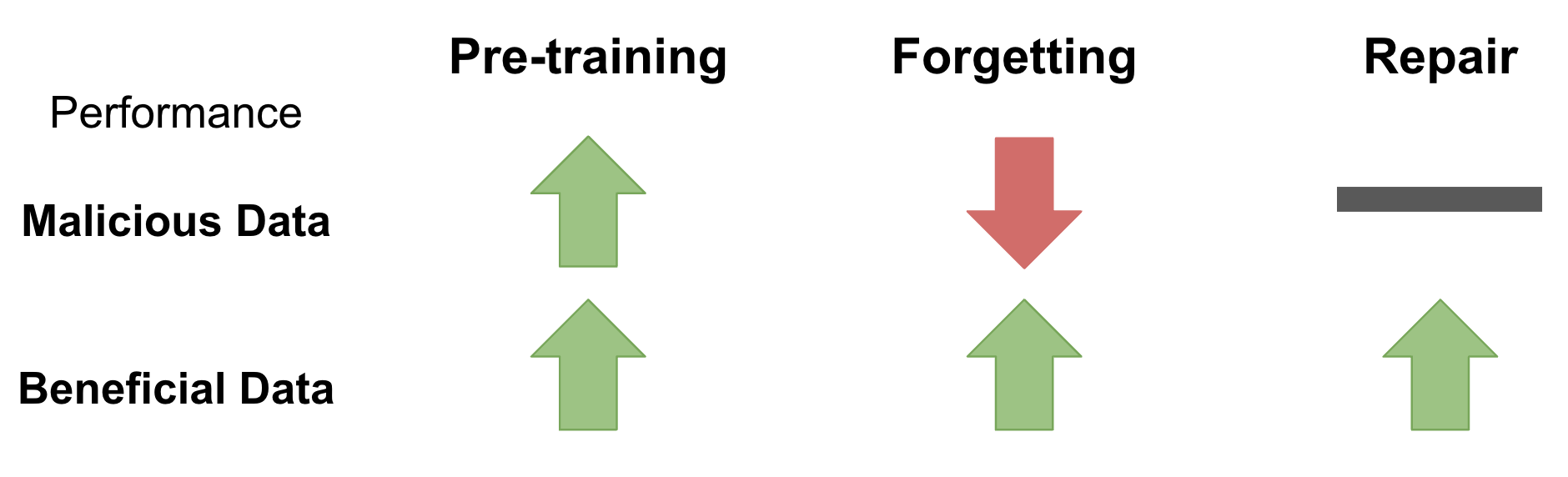

In this project, we study an opposing question: how to learn model weights that classify well for one dataset but reduce learning efficiency when transferred to another. The motivation is as follows. As computational resources and capable models become more accessible, the risk of unregulated agents fine-tuning existing models increases, including for malicious tasks. Recent work has shown that previously aligned models can be compromised to produce malicious or harmful outputs

To our knowledge, there exists no previous literature on learning parameters robust against transfer learning. A related field is machine unlearning. In machine unlearning, a model must forget certain pieces of data used in training

We propose two new approaches: selective knowledge distillation (SKD) and Reverse Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML)

Related Works

1. Transfer Learning

As mentioned previously, transfer learning has been a long-time objective in deep learning research

2. Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML)

MAML is an algorithm that makes models readily adaptable to new tasks

3. Machine Unlearning

A closely aligned question to ours is the problem of machine unlearning. Machine unlearning attempts to remove the influence of a set of data points on an already trained model. In this setting, a model is initially trained on some dataset

To our knowledge, there hasn’t been any research on models that are resistant to transfer learning and fine-tuning. The works mentioned above, transfer learning techniques and MAML, focus on improving fine-tuning. We aim to make fine-tuning more difficult while preserving robustness on the original task. Machine unlearning seeks to forget data that the model has been previously trained on. On the other hand, our goal is to preemptively guard the model from learning certain data in the first place. Thus, our research question demonstrates a clear gap in existing research which has focused on either improving transfer learning or only reducing model performance on external datasets. Our research explores this new question in the deep learning field and draws from recent works to guide methodology.

Methods

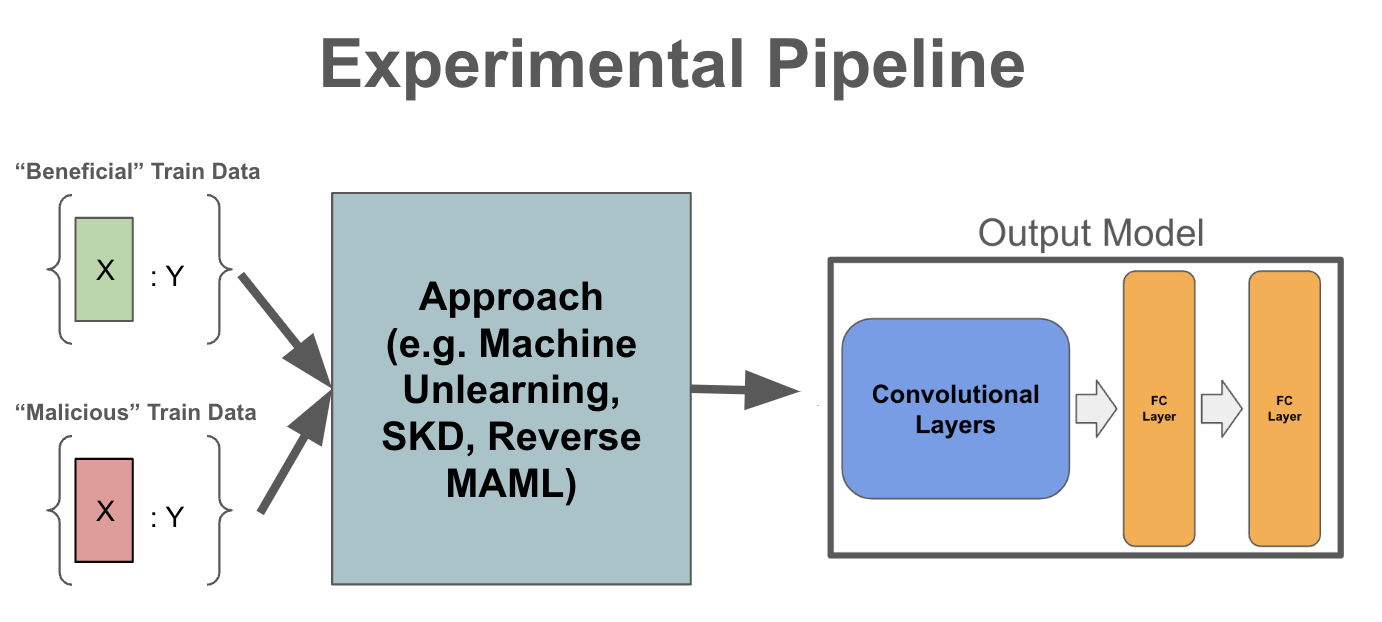

We propose three methods, one existing and two novel, to begin addressing the problem of learning parameters scoring high accuracy on a “beneficial” dataset but are robust against transfer learning on a known “malicious” dataset. Further experimental details are found in the experiments section.

1. Machine Unlearning

The first approach is a baseline and reimplementation of a popular machine unlearning method from

2. Selective Knowledge Distillation

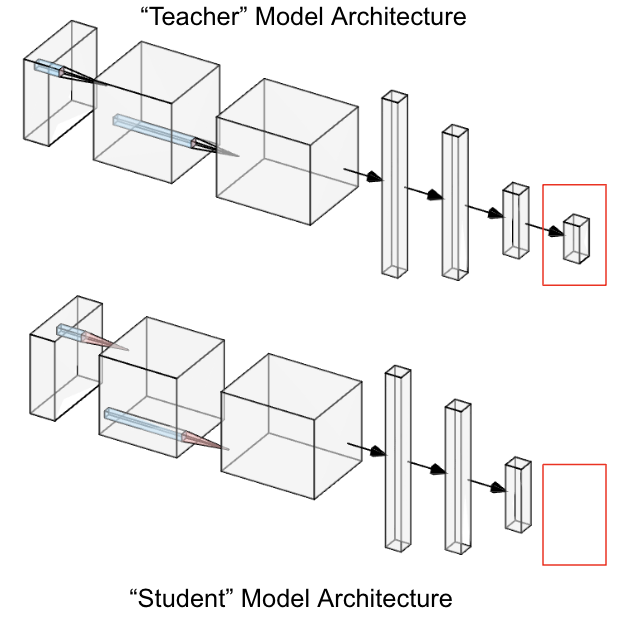

Our first proposed novel approach is selective knowledge distillation (SKD) drawing inspiration from knowledge distillation. In knowledge distillation, a smaller “student” model is trained to imitate a larger “teacher” model by learning logits outputs from the “teacher” model. In doing so, the “student” model can hopefully achieve similar performance to the “teacher” model while reducing model size and complexity.

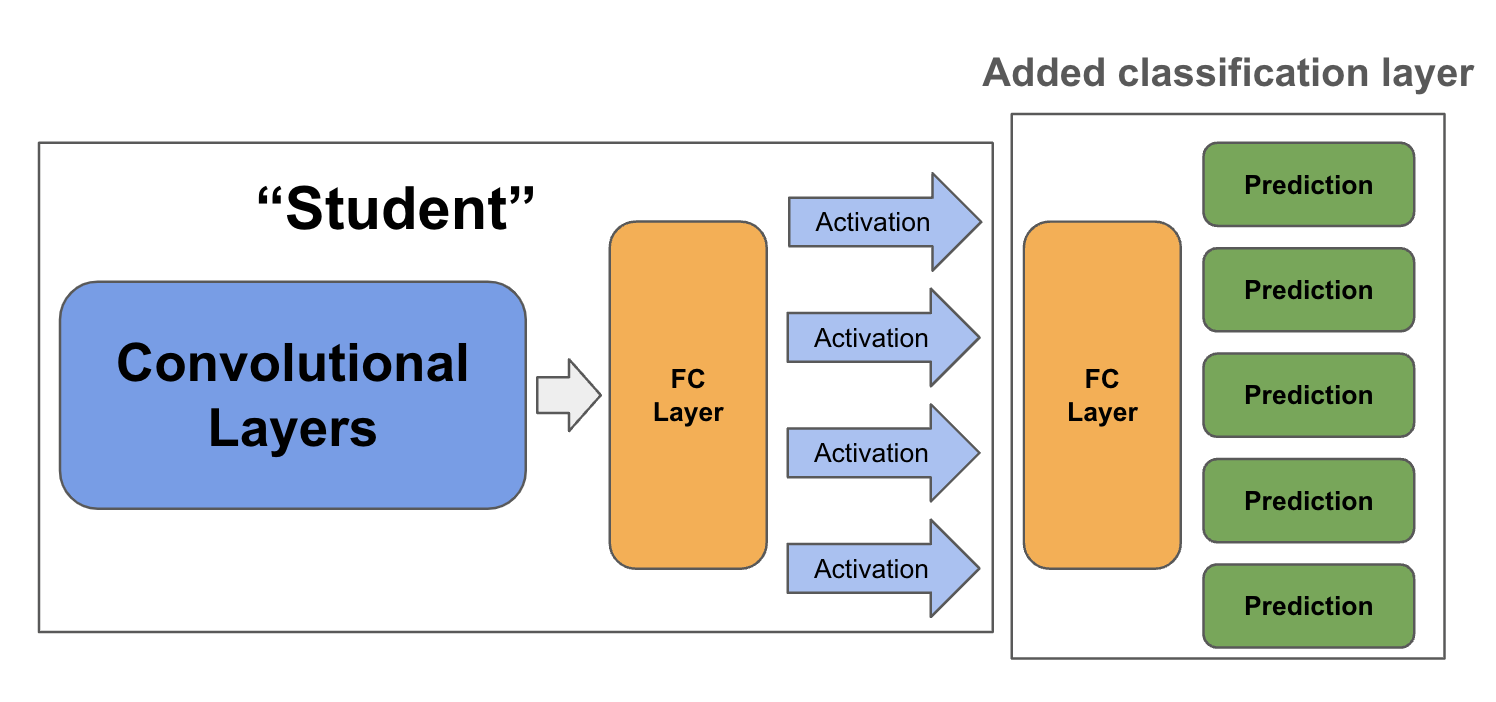

In SKD, we similarly have a “teacher” and “student” model. The “teacher” is a model that has high accuracy on the “beneficial” dataset but is not necessarily robust against fine-tuning on the “malicious” dataset. Our “student” model is almost identical in architecture to the “teacher” but excludes the final classification layer and the ReLU layer before it. This is shown below.

Our goal is for the student model to have high performance on the “beneficial” dataset after adding a classification layer while being robust against fine-tuning on the “malicious” dataset. To perform SKD, we initially train the teacher model until reaching sufficiently high performance on the “beneficial” dataset.

We then construct a dataset that contains all the images in the “beneficial” dataset. The labels are activations of the second-to-last layer of the “teacher” model. Note that this is similar to knowledge distillation, except we are taking the second-to-last layer’s activations. We further add all the images in the “malicious” dataset and set their labels to be a vector of significantly negative values. For our experiments, we used -100.0. We train the student model on this collective dataset of images and activation values.

Finally, we add a fully-connected classification layer to the student model and backpropagate only on the added layer with the “beneficial” dataset.

Our end goal is to prevent fine-tuning of our CNN on the “malicious” dataset. Thus, if the student model can output activations that all are negative if the image belongs in the “malicious” dataset, then after appending the ReLU layer and setting biases of the second-to-last layer to 0, the inputs to the final classification layer will always be 0, reducing the ability to learn on the “malicious” dataset. Furthermore, the gradient will always be 0 on inputs from the “malicious” dataset so any backpropagating on images and labels originating from the “malicious” dataset from the final layer activations would be useless.

3. Reverse-MAML

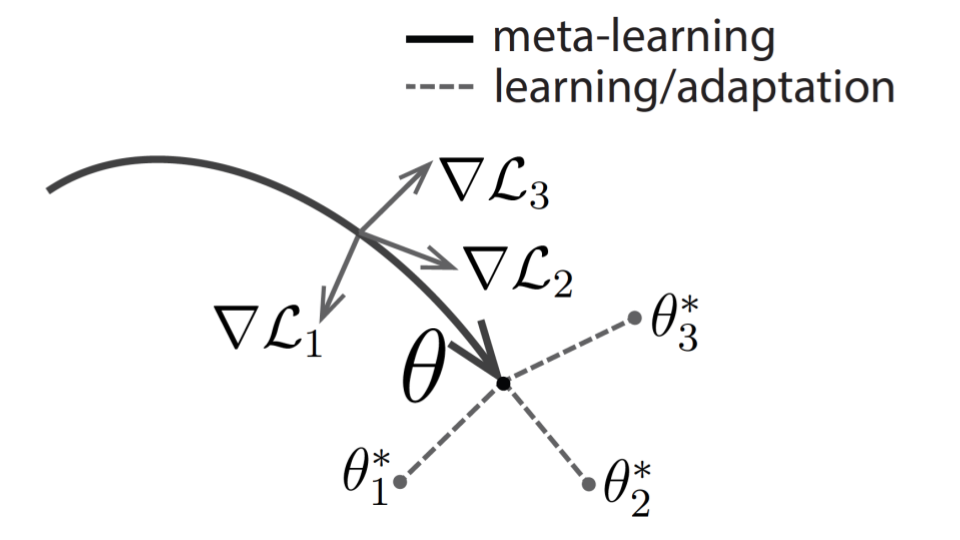

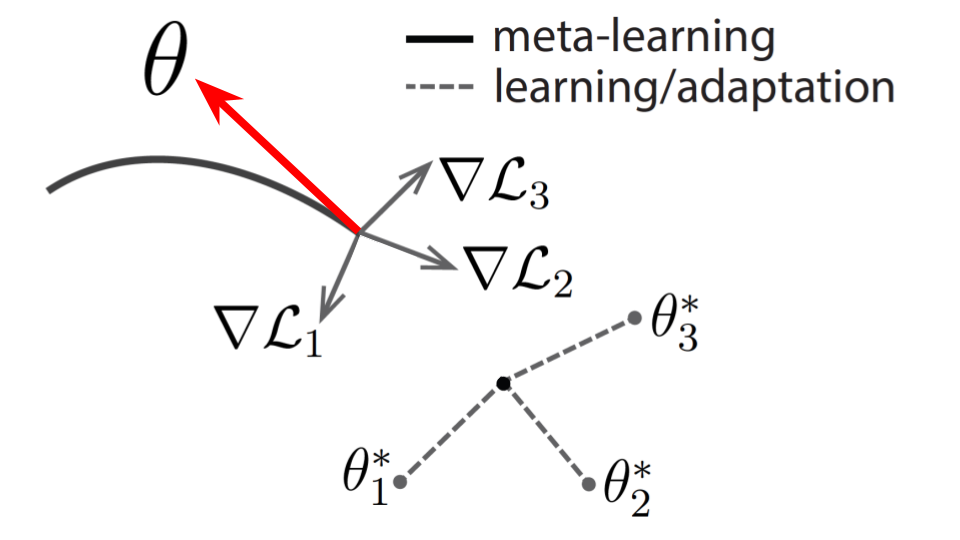

Recall that MAML is focused on finding some optimal set of model weights \(\theta\) such that running gradient descent on the model from a new few-shot learning task results in a \(\theta’\) that scores high accuracy on the new task

In our version, we attempt to learn a \(\theta\) that fine-tunes well to a data distribution \(p_1\) but fine-tunes poorly to distribution \(p_2\). To do this, we partition the data into two sets: a “good” set and a “bad” set. We train such that for “good” samples MAML performs the standard algorithm above, learning \(\theta\) that would fine-tune well to the “good” samples. However, for the “bad” set we train the model to do the opposite, learning a \(\theta\) that would lead to poor fine-tuning. To do this, when taking the second order gradient, the model goes up the gradient instead of down.

Experiments

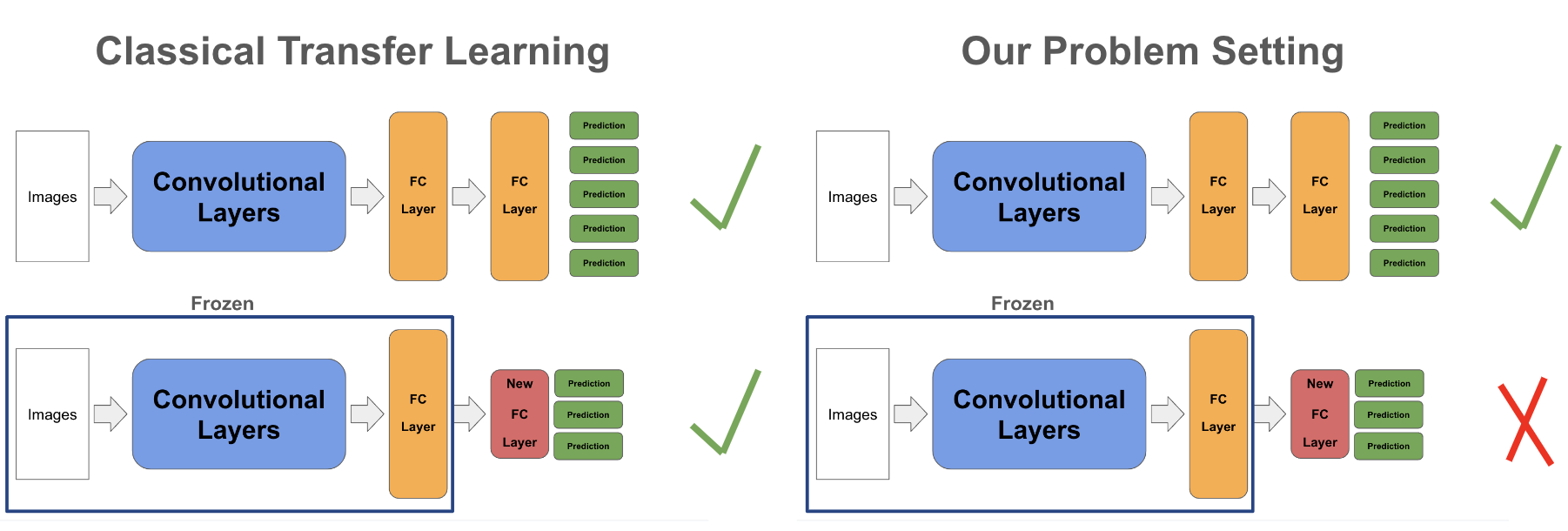

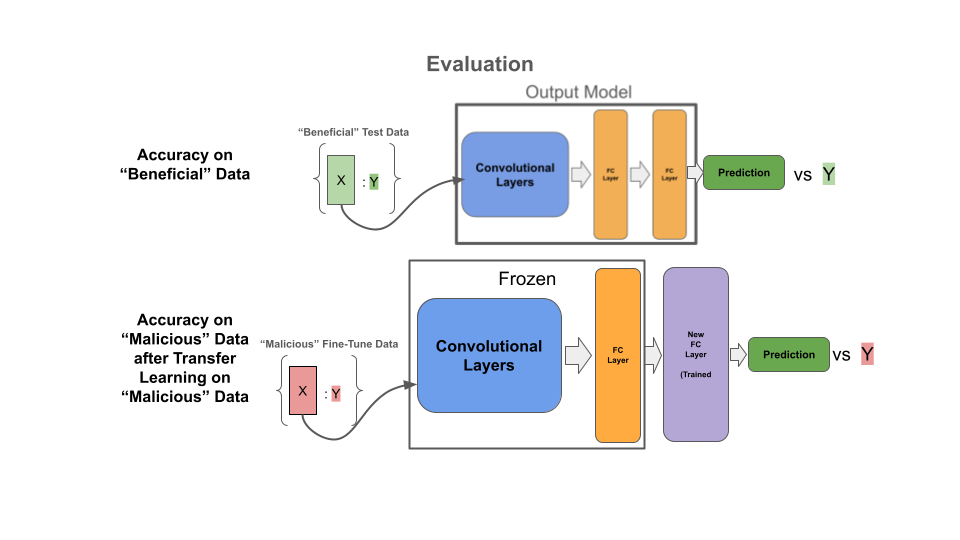

Due to computational constraints, we work in the following toy setting. We use the CIFAR-10 dataset where images in the first five ([0, 4]) classes are the “beneficial” dataset and the images in the last five ([5, 9]) classes are the “malicious” dataset. We split the 60,000 CIFAR-10 image dataset into a 40,000 image pre-training dataset, 10,000 image fine-tuning dataset, and 10,000 image test dataset. To evaluate each approach, we first evaluate the accuracy of the model on the beneficial test dataset. Then, we replace the last layer parameters of the output model, freeze all previous layer’s parameters, and finally fine-tune on the malicious fine-tuning dataset. We fine-tune using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.1 and momentum of 0.9. We finally evaluate model performance on a malicious test dataset. These steps in this evaluation represent the common pipeline to perform transfer learning and are shown below. Full hyperparameters for evaluation are listed in the appendix. We also perform ablation studies on the quality of the teacher model for SKD; further details are found in the Discussion section. All experiments, including ablations, are performed and averaged over 5 random seeds.

Results

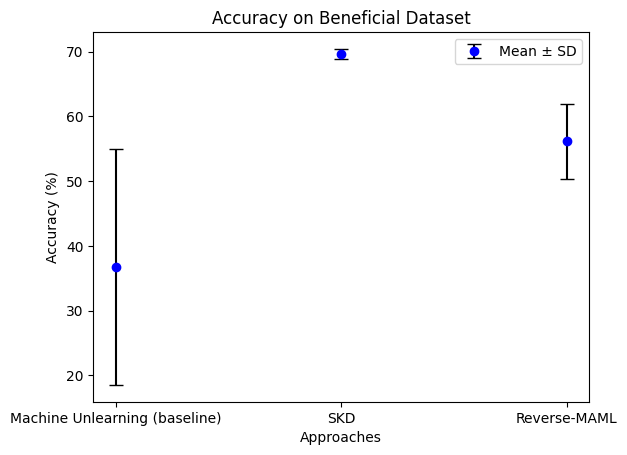

The first evaluation metric is accuracy of the outputted model from each approach on beneficial data. This is shown in the figure below.

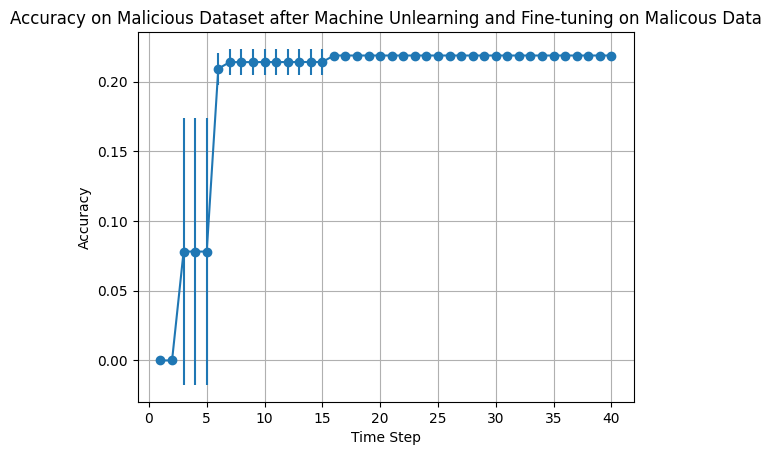

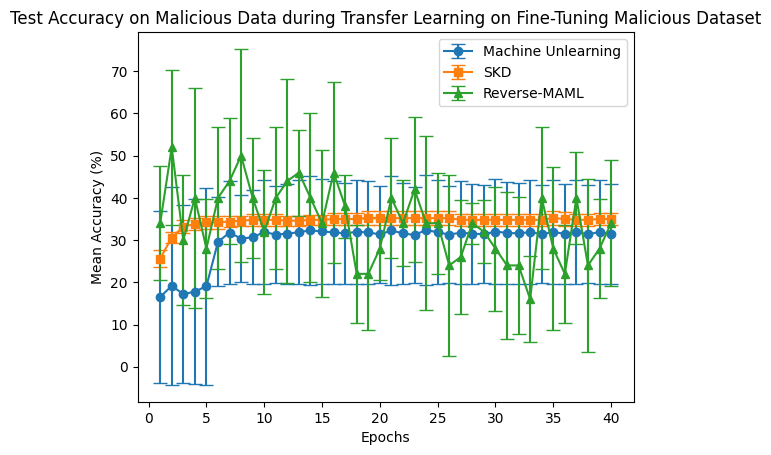

The second metric of evaluation is the accuracy of the output model from each approach on test malicious data as it’s being fine-tuned on fine-tune malicious data. This is shown with learning curves in the figure below. Note that lower accuracy is better.

Discussion

We observe that finding parameters that have high accuracy on a “beneficial” dataset but are robust against fine-tuning on a “malicious” dataset is challenging. On all three methods, including a popular machine unlearning approach, the model is able to somewhat fit to the “malicious” dataset. However, for SKD, this accuracy consistently does not significantly exceed 40%.

More importantly, we find in Figure 1 that both Reverse-MAML and SKD are able score higher accuracy on the beneficial dataset. This is surprising as machine unlearning methods were designed to maintain high accuracy on a retain dataset. Combining these two graphs, we conclude that there remains future work to explain why the resulting models had such high accuracy on the malicious data out-of-the-box and how to minimize it.

We also experimented with Reverse-MAML under the Omniglot dataset

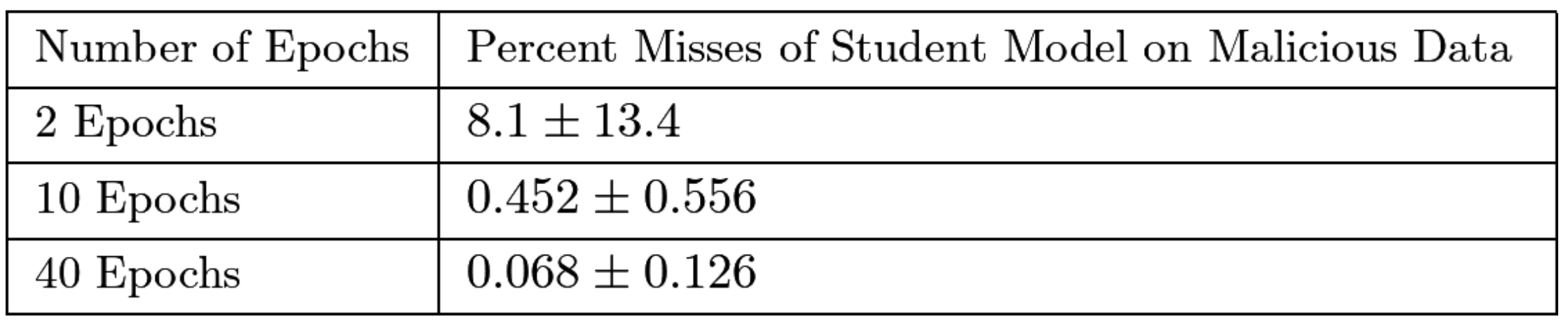

Slow learning in SKD is likely caused by filtering by the ReLU activation function which causes activations to become 0. This ideally occurs when we train the student model to output negative activation values into the final classification layer if the input is from the “malicious” dataset. These values make it more difficult to learn useful weights for the final classification layer and apply gradient descent on earlier layers. We confirm this by measuring misses or the percent of “malicious” images that don’t result in all 0 activations into the final classification layer shown below. We show, in general, misses are low across different teacher models. For this ablation, we vary teacher models by the number of epochs they are trained.

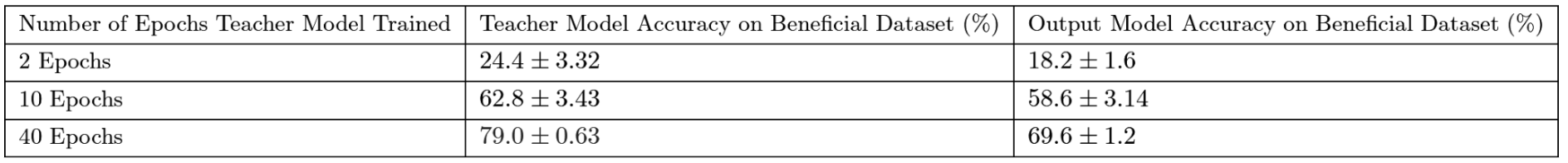

We also measure how accuracy of the teacher model impacts performance of the student downstream. We vary the number of epochs the teacher model is trained in and report accuracies of the teacher model on the “beneficial” dataset below. More importantly, we empirically show that high teacher accuracy on the “beneficial” dataset is needed for the student to achieve high accuracy on the “beneficial” dataset. This follows our knowledge distillation framework as the student attempts to mimic the teacher model’s performance on the “beneficial” dataset by learning activation values.

Limitations and Future Work

1. Requirement for “Malicious” data

The motivating example for this project was preventing a malicious agent from hijacking a model to perform undesirable tasks. However, it is often not possible to list out every possible “bad” task, and thus future work which extends from this project can explore how to prevent fine-tuning of tasks that aren’t specified as clearly and completely.

2. Computational Restraints

Due to computational restraints, we were unable to test or fine-tune models with significantly higher parameter counts or experiment with larger datasets. However, this remains an important step as transfer learning or fine-tuning is commonly applied on large models which we could not sufficiently investigate. Thus, future work can apply these existing methods on larger models and datasets.

3. Exploration of More Methods in Machine Unlearning and Meta-Learning

Further analysis of existing methods in machine unlearning and meta-learning can be used to benchmark our proposed approaches. Though we tried to select methods that had significant impact and success in their respective problem settings, other approaches are promising, including using MAML variants like Reptile or FOMAML

4. Imperfection in filtering “malicious” data for SKD

Ideally, in SKD, the underlying model would always output negative activation values given a “malicious” input. However, this does not always occur, and thus fitting on the malicious data is still possible. Future work can explore how to improve this, though perfect accuracy will likely not be feasible. Furthermore, it is still possible for a malicious agent to hijack the model by performing distilled learning on the second-to-last layer activations, thus removing this ideal guarantee. Future work can also investigate how to have similar guarantees throughout all of the model’s activation layers instead of just one.

Conclusion

In this project, we investigated how to train a model such that it performs well on a “beneficial” dataset but is robust against transfer learning on a “malicious” dataset. First, we show this is a challenging problem, as existing state of the art methods in machine unlearning are unable to prevent fine-tuning. We then propose two new approaches: Reverse-MAML and SKD. Both serve as a proof of concept with promising preliminary results on the CIFAR-10 Dataset. We conclude by noting there are limitations to this work, most notably the need for a “malicious” dataset and computational limits. We then propose future work stemming from these experiments.

Appendix

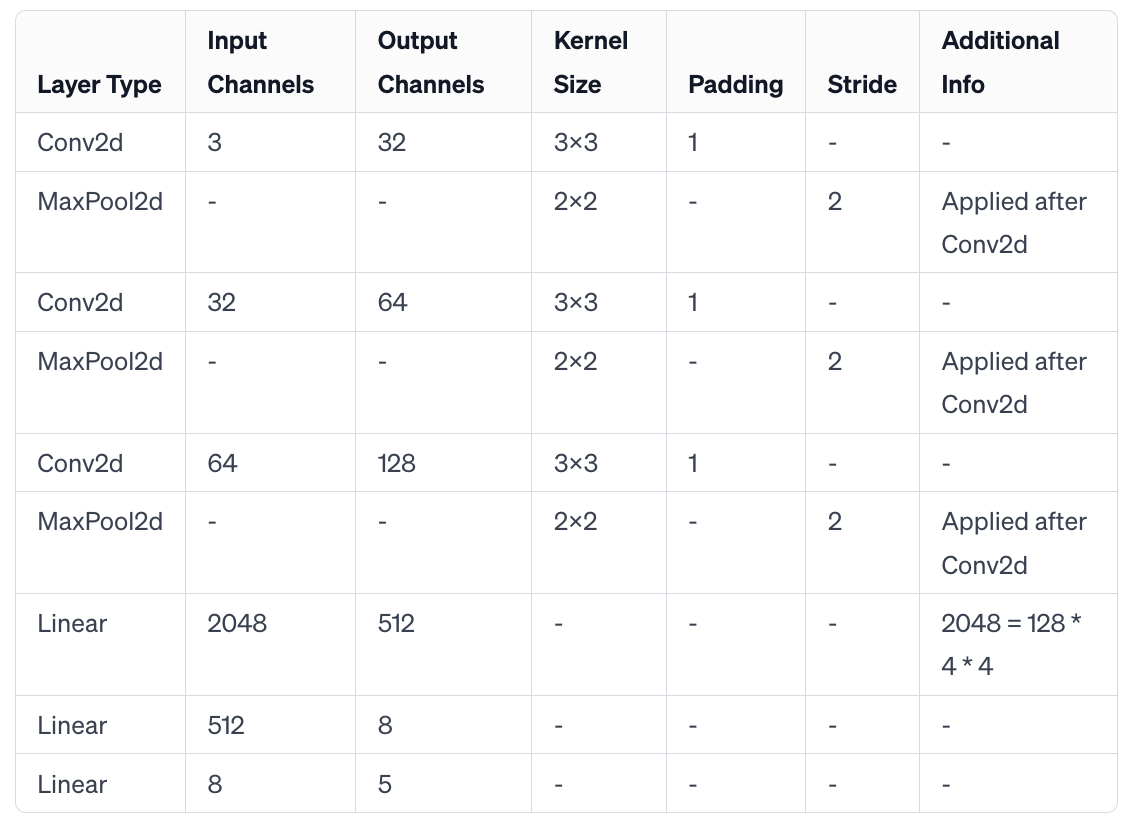

CNN Architectures used for experiments:

- Note, all graphs and tables are averaged over 5 seeds with reported standard deviation.