From Scroll to Misbelief - Modeling the Unobservable Susceptibility to Misinformation on Social Media

Abstract

Susceptibility to misinformation describes the extent to believe false claims, which is hidden in people’s mental process and infeasible to observe. Existing susceptibility studies heavily rely on the crowdsourced self-reported belief level, making the downstream research homogeneous and unscalable. To relieve these limitations, we propose a computational model that infers users’ susceptibility levels given their reposting behaviors. We utilize the supervision from the observable sharing behavior, incorporating a user’s susceptibility level as a key input for the reposting prediction task. Utilizing the capability of large-scale susceptibility labeling, we could also perform a comprehensive analysis of psychological factors and susceptibility levels across professional and geographical communities. Hopefully, we could observe that susceptibility is influenced by complicated factors, demonstrating a degree of correlation with economic development around the world, and with political leanings in the U.S.

Introduction

False claims spread on social media platforms, such as conspiracy theories, fake news, and unreliable health information, mislead people’s judgment, promote societal polarization, and decrease protective behavior intentions

Existing works have investigated the psychological, demographic, and other factors that may contribute to the high susceptibility of a population

The unobservance of people’s beliefs makes it infeasible to model susceptibility directly. Luckily, existing psychological literature bridges unobservable beliefs and observable behaviors, showing that the sharing behavior is largely influenced by whether users believe the misinformation

Concretely, we propose to infer people’s susceptibility level given their re/posting behaviors. To parameterize the model, we wrap the susceptibility level as input for the prediction model of the observable reposting behavior. We perform multi-task learning to simultaneously learn to classify whether a user would share a post, and rank susceptibility scores among similar and dissimilar users when the same content is seen. Note that our model does not aim to predict any ground-truth susceptibility for individuals. Instead, we use users’ reposting behaviors towards misinformation as a proxy for their susceptibility level for better interpretability. Our model design enables unobservable modeling with supervision signals for observable behavior, unlocks the scales of misinformation-related studies, and provides a novel perspective to reveal the users’ belief patterns.

We conduct comprehensive evaluations to validate the proposed susceptibility measurement and find that the estimations from our model are highly aligned with human judgment. Building upon such large-scale susceptibility labeling, we further conduct a set analysis of how different social factors relate to susceptibility. We find that political leanings and psychological factors are associated with susceptibility in varying degrees. Moreover, our analysis based on these inferred susceptibility scores corroborates the findings of previous studies based on self-reported beliefs, e.g., stronger analytical thinking is an indicator of low susceptibility. The results of our analysis extend findings in existing literature in a significant way. For example, we demonstrate that susceptibility distribution in the U.S. exhibits a certain degree of correlation with political leanings.

To sum up, our contributions are:

- We propose a computational model to infer people’s susceptibility towards misinformation in the context of COVID-19, by modeling unobservable latent susceptibility through observable sharing activities.

- Evaluation shows that our model effectively models unobservable belief, and the predictions highly correlate with human judgment.

- We conduct a large-scale analysis to uncover the underlying factors contributing to susceptibility across a diverse user population from various professional fields and geographical regions, presenting important implications for related social science studies.

Computational Susceptibility Modeling

Modeling Unobservable Susceptibility

Inspired by the existing studies indicating that believing is an essential driver for dissemination, we propose to model susceptibility, which reflects users’ beliefs, as a driver for the sharing behavior, while considering characteristics of the sharing content and user profile.

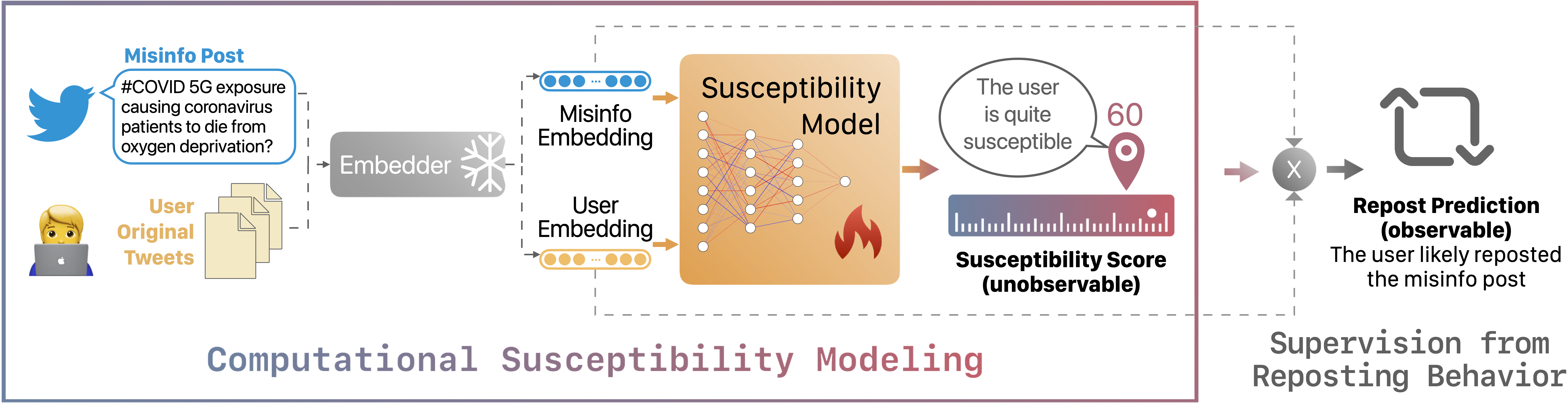

We propose a computational model to infer a user’s unobservable susceptibility score based on their historical activities as shown in the model figure, and further train the model with signals from the observable disseminating behavior. We construct approximate contrastive user-post pairs as the training data (Dataset and Experiment Setup).

This design would allow us to explore the best parameters for the computational model of an unobservable and data-hungry susceptibility variable using the rich data resources available on social media platforms.

Content-Sensitive Susceptibility

We compute the user’s susceptibility when a particular piece of misinformation $p$ is perceived (i.e. $s_{u, p}$). This allows us to account for the fact that an individual’s susceptibility can vary across different content, influenced by factors such as topics and linguistic styles. By focusing on the susceptibility to specific pieces of misinformation, we aim to create a more nuanced, fine-grained, and accurate representation of how users interact with and react to different COVID-19 misinformation.

User and Misinfo Post Embeddings

As a component of the computational model, we use SBERT developed upon RoBERTa-large to produce a fixed-sized vector to represent the semantic information contained in the posts and user profiles. We consider the misinformation post as a sentence and produce its representation with SBERT. For the user profile, we calculate the average of sentence representations for the user’s recent original posts. More specifically, for every user-post pair $(u, p)$, we gather the historical posts written by user $u$ within a 10-day window preceding the creation time of the misinformation post $p$, to learn a representation of user $u$ at that specific time.

Computational Model for Susceptibility

Given the input of the user profile for the user $u$ and the content for misinformation post $p$, the susceptibility computational model is expected to produce the susceptibility score $s_{u, p}$ as shown below, reflecting the susceptibility of $u$ when $p$ is perceived.

\[s_{u, p} = suscep(E(u), E(p))\]We first obtain the embeddings $E(p)$ and $E(u)$ for post $p$ and user profile $u$, where $u$ is represented by the user’s historical tweets and $E$ is the frozen SBERT sentence embedding function. The susceptibility score is calculated by the function $suscep$, which is implemented as a multi-layer neural network, taking the concatenation of the user and post embeddings as inputs. In the training phase, we keep the sentence embedder frozen and learn the weights for the $suscep$ function that could be used to produce reasonable susceptibility scores. We expect to produce susceptibility scores for novel $u$ and $p$ pairs using the learned $suscep$ function during inference. Additionally, we normalize the resulting susceptibility scores into the -100 to 100 range for better interpretability.

Training with Supervision from Observable Behavior

Susceptibility is not easily observable, thus it is infeasible to apply supervision on $s_{u, p}$ directly as only the user $u$ themselves know their belief towards content $p$. Thus, we propose to utilize the supervision signal for sharing a piece of misinformation, which is an observable behavior. We consider susceptibility as an essential factor of sharing behavior and use the susceptibility computational model’s output to predict the repost behavior.

To produce the probability for user $u$ to share post $p$, we calculate the dot product of the embeddings of the user profile and post content and consider the susceptibility score for the same pair of $u$ and $p$ as a weight factor, and passing the result through a sigmoid function, as illustrated in the model figure.

\[p_{\text{rp}} = \sigma \left( E(u) \cdot E(p) \cdot s_{u, p} \right)\]Note that we do not directly employ the \textit{susceptibility score} to compute the probability of sharing because the sharing behavior depends not only on the susceptibility level but also on other potential confounding factors. It is possible that a user possesses a notably high susceptibility score for a piece of misinformation yet chooses not to repost it. Hence, we incorporate a dot product of the user and post embedding in our model \dkvtwo{involve the misinformation post content and user profiles into the consideration of predicting the sharing behavior}.

\(\begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\text{bce}}(u_i, t) &= -\left( y_i \log(p_{\text{rt}}(u_i, t)) + (1 - y_i) \log(1 - p_{\text{rt}}(u_i, t)) \right) \nonumber \\ \mathcal{L}_{\text{triplet}}(u_a, u_s, u_{ds}, t) &= \text{ReLU}\left(\Vert s_{u_{a},t} - s_{u_{s},t}\Vert_2^2 - \Vert s_{u_{a},t} - s_{u_{ds},t} \Vert_2^2 + \alpha \right) \nonumber \\ \mathcal{L}(u_a, u_s, u_{ds}, t) &= \frac{\lambda}{3} \sum_{i \in \{a, s, ds\}} \mathcal{L}_{\text{bce}}(u_i, t) + (1 - \lambda) \mathcal{L}_{\text{triplet}}(u_a, u_s, u_{ds}, t) \nonumber \label{eq:loss} \end{align}\)

Objectives

We perform multi-task learning to utilize different supervision signals. We first consider a binary classification task of predicting repost or not with a cross-entropy loss. Additionally, we perform the triplet ranking task

During each forward pass, our model is provided with three user-post pairs: the anchor pair $(u_a, p)$, the similar pair $(u_s, p)$, and the dissimilar pair $(u_{ds}, p)$. We determine the similar user $u_s$ as the user who reposted $p$ if and only if user $u_a$ reposted $p$. Conversely, the dissimilar user $u_{ds}$ is determined by reversing this relationship. When multiple potential candidate users exist for either $u_s$ or $u_{ds}$, we randomly select one. However, if there are no suitable candidate users available, we randomly sample one user from the positive (for “reposted” cases) or negative examples (for “did not repost” cases) and pair this randomly chosen user with this misinformation post $p$.

Here, we elaborate on the definition of our loss function. Here, $y_i$ takes the value of 1 if and only if user $u_i$ reposted misinformation post $p$. The parameter $\alpha$ corresponds to the margin employed in the triplet loss, serving as a hyperparameter that determines the minimum distance difference needed between the anchor and the similar or dissimilar sample for the loss to equal zero. Additionally, we introduce the control hyperparameter $\lambda$, which governs the weighting of the binary cross-entropy and triplet loss components.

Dataset and Experiment Setup

We use Twitter data because it hosts an extensive and diverse collection of users, the accessibility of its data, and its popularity for computational social science research

Misinformation Tweets

We consider two misinformation tweet datasets: the ANTi-Vax dataset

However, a substantial number of tweets within these two datasets do not have any retweets. Consequently, we choose to retain only those misinformation tweets that have been retweeted by valid users. Finally, we have collected a total of 1,271 misinformation tweets for our study.

Positive Examples

We define the positive examples for modeling as $(u_{pos}, t)$ pairs, where user $u_{pos}$ viewed and retweeted the misinformation tweet $t$. We obtained all retweeters for each misinformation tweet through the Twitter API.

Negative Examples

Regarding negative examples, we define them as $(u_{neg}, t)$ pairs where user $u_{neg}$ viewed but did not retweet misinformation post $t$. However, obtaining these negative examples poses a substantial challenge, because the Twitter API does not provide information on the “being viewed” activities of a specific tweet. To tackle this issue, we infer potential users $u_{neg}$ that highly likely viewed a given tweet $t$ following the heuristics: 1) $u_{neg}$ should be a follower of the author of the misinformation tweet $t$, 2) $u_{neg}$ should not retweet $t$, and 3) $u_{neg}$ was active on Twitter within 10 days before and 2 days after the timestamp of $t$.

We have collected a total of 3,811 positive examples and 3,847 negative examples, resulting in a dataset comprising 7,658 user-post pairs in total. We divide the dataset into three subsets with an 80% - 10% - 10% split for train, validation, and test purposes, respectively. The detailed statistics of the collected data are illustrated in the table below.

| Total | Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Example | 7658 | 3811 | 3847 |

| # User | 6908 | 3669 | 3255 |

| # Misinfo tweet | 1271 | 787 | 1028 |

Evaluation

In this section, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our susceptibility modeling by directly comparing our estimations with human judgment and indirectly evaluating its performance for predicting sharing behavior.

Validation with Human Judgement

Due to the abstract nature of susceptibility and the lack of concrete ground truth, we face challenges in directly evaluating our susceptibility modeling. We use human evaluations to validate the effectiveness of our inferred susceptibility. Given the subjectivity inherent in the concept of susceptibility, and to mitigate potential issues arising from variations in individual evaluation scales, we opt not to request humans to annotate a user’s susceptibility directly. Instead, we structure the human evaluation as presenting human evaluators with pairs of users along with their historical tweets and requesting them to determine which user appears more susceptible to overall COVID-19 misinformation.

Subsequently, we compared the predictions made by our model with the human-annotated predictions. To obtain predictions from our model, we compute each user’s susceptibility to overall COVID-19 misinformation by averaging their susceptibility scores to each COVID-19 misinformation tweet in our dataset. As presented in the table below, our model achieves an average agreement of 73.06% with human predictions, indicating a solid alignment with the annotations provided by human evaluators. Additionally, we consider a baseline that directly calculates susceptibility scores as the cosine similarity between the user and misinformation tweet embeddings. Compared to this baseline, our susceptibility modeling brings a 10.06% improvement. Moreover, we compare the performance with ChatGPT prompting with the task description of the susceptibility level comparison setting as instruction in a zero-shot manner. We observe that our model also outperforms predictions made by ChatGPT. The results from the human judgment validate the effectiveness of our susceptibility modeling and its capability to reliably assess user susceptibility to COVID-19 misinformation.

| Our | Baseline | ChatGPT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | 73.06±8.19 | 63.00±9.07 | 64.85±9.02 |

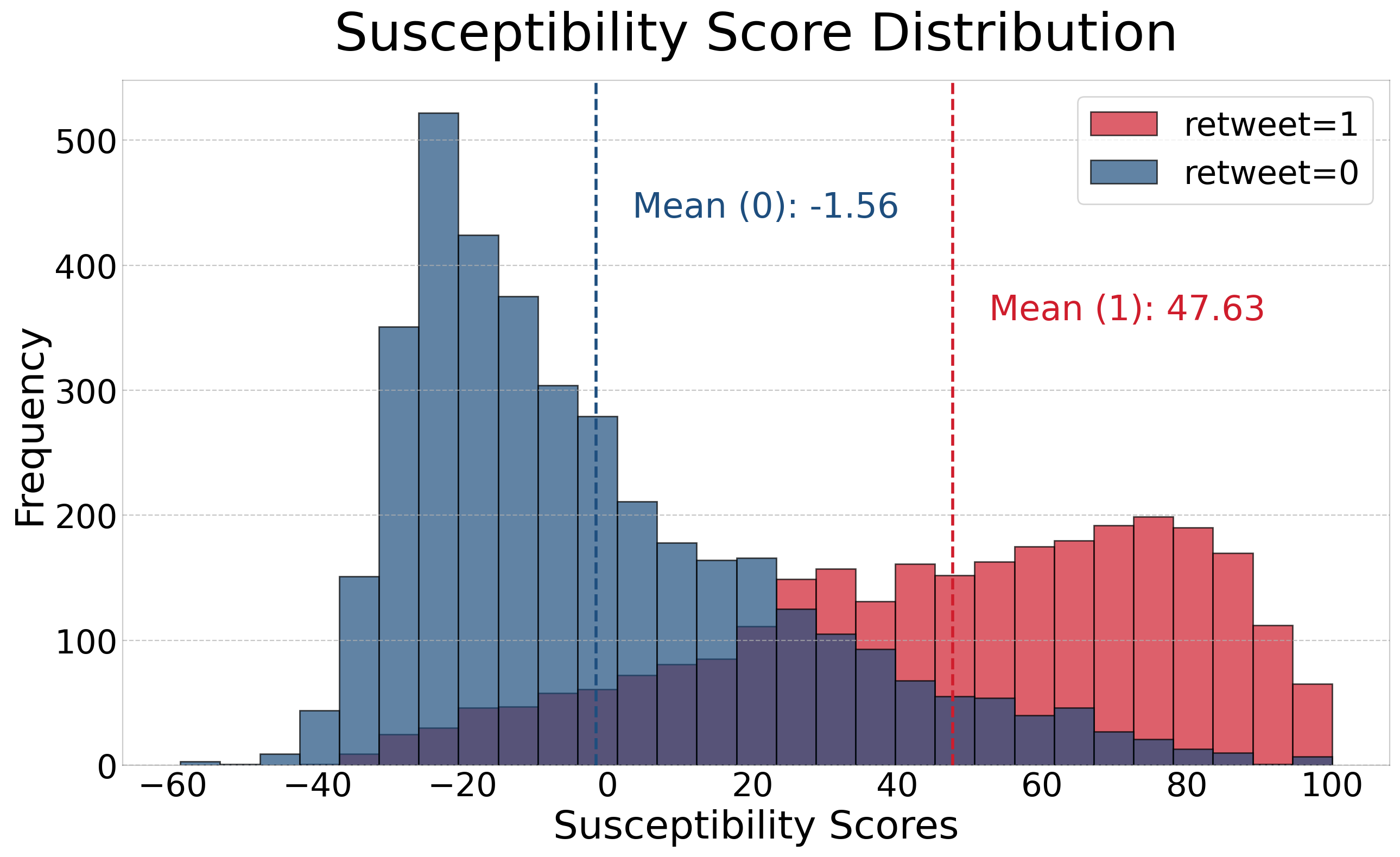

Susceptibility Score Distribution

We provide a visualization of the distribution of susceptibility scores within positive and negative examples produced by our model on the training data. As depicted below, there is a notable disparity in the distribution between positive and negative examples, verifying our assumption that believing is an essential driver for sharing behavior. The difference in the means of the positive and negative groups is statistically significant, with a p-value of less than 0.001.

Sharing Behavior Prediction

Furthermore, holding a belief is highly likely to result in subsequent sharing behavior. We demonstrated that our trained model possesses a strong ability for sharing behavior prediction. When tested on the held-out test dataset, our model achieves a test accuracy of 78.11% and an F1 score of 77.93. These results indirectly demonstrate the reliable performance of our model for susceptibility modeling.

Analysis

In this section, we show the potential of our inferred susceptibility scores in expanding the scope of susceptibility research. Our analysis not only aligns with the findings of previous survey-based studies but also goes a step further by extending and enriching their conclusions.

Correlation with Psychological Factors

Previous research on human susceptibility to health and COVID-19 misinformation has been primarily based on questionnaire surveys

To achieve this, we compute factor scores for each user in our dataset based on their historical tweets using LIWC Analysis. We calculate the average value across all the user’s historical tweets as the final factor score. However, for emotional factors such as anxiety and anger with less frequent appearance, we opt for the maximum value instead to more effectively capture these emotions. We primarily consider the following factors: Analytic Thinking, Emotions (Positive emotions, Anxious, Angery and Sad), Swear, Political Leaning, Ethnicity, Technology, Religiosity, Illness and Wellness. These factors have been extensively studied in previous works and can be inferred from a user’s historical tweets. We calculate and plot the Pearson correlation coefficients between each factor and the susceptibility predicted by our model in the following table.

| Factors | Coeff. | Factors | Coeff. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytic Thinking | -0.31 | Emotion - Positive | -0.08 |

| Political Leaning | 0.13 | Emotion - Anxious | 0.08 |

| Ethnicity | 0.09 | Emotion - Angry | 0.16 |

| Religiosity | 0.10 | Emotion - Sad | 0.14 |

| Technology | -0.09 | Swear | 0.18 |

| Illness | 0.09 | Wellness | -0.02 |

According to our analysis, correlations are consistent with previous social science studies based on surveys on health susceptibility. For instance, Analytic Thinking is a strong indicator of low susceptibility, with a correlation coefficient of -0.31. Conversely, certain features such as Swear, Political Leaning and Angry exhibit a weak correlation with a high susceptibility score. These results not only corroborate the conclusions drawn from previous survey-based studies

Geographical Community Differences

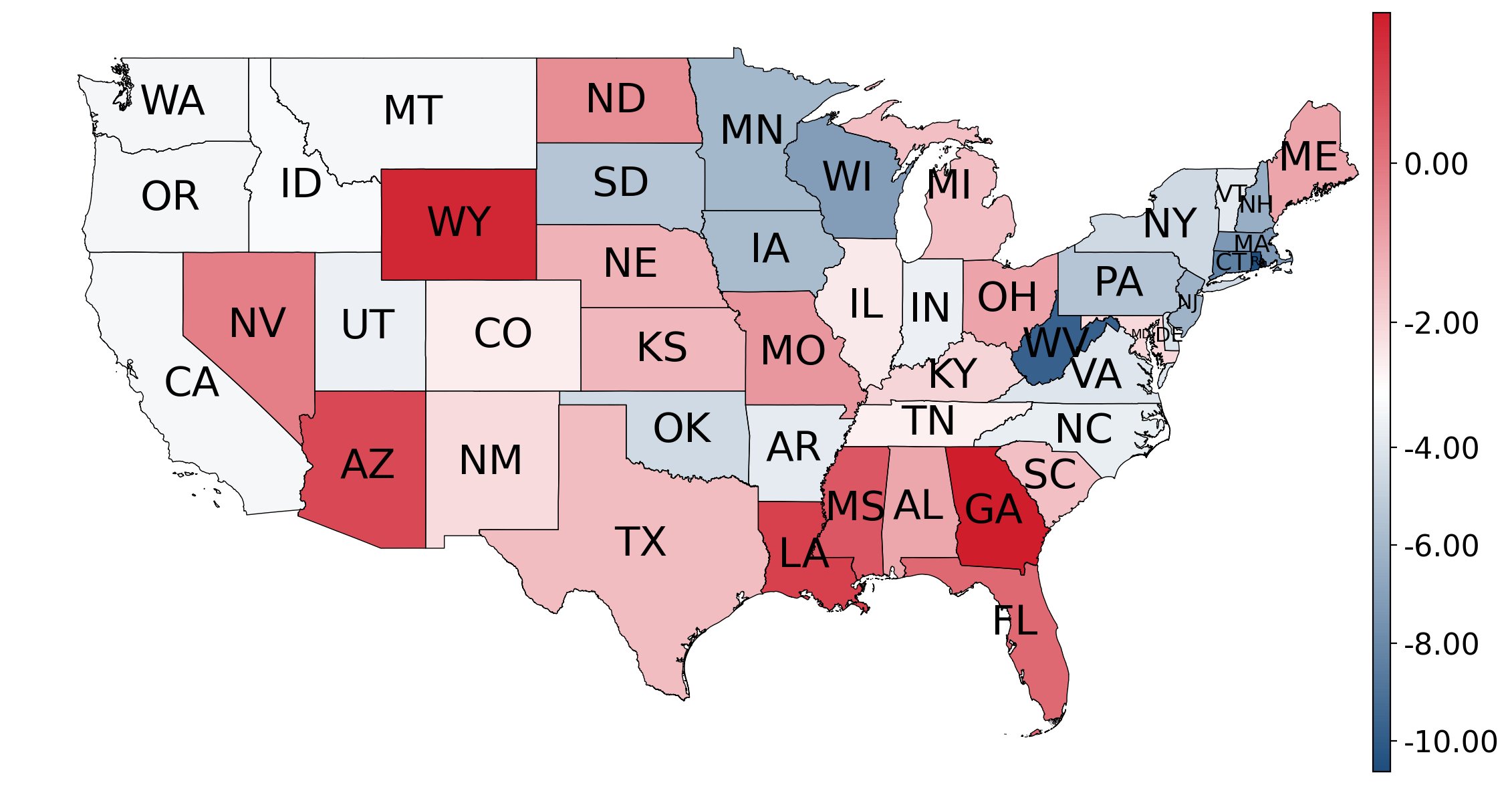

We delve into the geographical distribution of susceptibility. Given the significant imbalance in the number of users from different U.S. states, we calculate the average susceptibility scores for each state using Bayesian smoothing. We use the overall mean susceptibility score and overall standard deviation as our priors and the more the users in the group, the less the overall mean will affect the group’s score.

We explore the susceptibility distribution among different U.S. states, considering the influence of political ideology associated with different states

Related Work

Measure of Susceptibility

The common practice in measuring susceptibility involves collecting self-reported data on agreement or disagreement with verified false claims

Contributing Factors and Application of Susceptibility

Research utilizing manually collected susceptibility annotations has explored various factors influencing susceptibility, such as emotion

Inferring Unobservables from Observables

Latent constructs, or variables that are not directly observable, are often inferred through models from observable variables

Conclusion

In this work, we propose a computational approach to model people’s unobservable susceptibility to misinformation. While previous research on susceptibility is heavily based on self-reported beliefs collected from questionnaire-based surveys, our model trained in a multi-task manner can approximate user’s susceptibility scores from their reposting behavior. When compared with human judgment, our model shows highly aligned predictions on a susceptibility comparison evaluation task. To demonstrate the potential of our computational model in extending the scope of previous misinformation-related studies, we leverage susceptibility scores generated by our model to analyze factors contributing to misinformation susceptibility. This thorough analysis encompasses a diverse U.S. population from various professional and geographical backgrounds. The results of our analysis algin, corroborate, and expand upon the conclusions drawn from previous survey-based computational social science studies.

Limitations

Besides investigating the underlying mechanism of misinformation propagation at a large scale, the susceptibility scores produced by our model have the potential to be used to visualize and interpret individual and community vulnerability in information propagation paths, identify users with high risks of believing in false claims and take preventative measures, and use as predictors for other human behavior such as following and sharing. However, while our research represents a significant step in modeling susceptibility to misinformation, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, our model provides insights into susceptibility based on the available data and the features we have incorporated. However, it’s important to recognize that various other factors, both individual and contextual, may influence susceptibility to misinformation. These factors, such as personal experiences and offline social interactions, have not been comprehensively incorporated into our model and should be considered in future research.

Moreover, the susceptibility scores modeled by our model represent an estimation of an individual’s likelihood to engage with misinformation. These scores may not always align perfectly with real-world susceptibility levels. Actual susceptibility is a complex interplay of cognitive, psychological, and social factors that cannot be entirely captured through computational modeling. Our model should be seen as a valuable tool for understanding trends and patterns rather than providing definitive individual susceptibility assessments.

Finally, our study’s findings are based on a specific dataset and may not be fully generalizable to all populations, platforms, or types of misinformation. For example, due to the high cost of data collection, not all countries or U.S. states have a sufficient amount of Twitter data available for analysis, especially when we examine the geographical distribution of susceptibility. Furthermore, platform-specific differences and variations in the types of misinformation can potentially impact the effectiveness of our model and the interpretation of susceptibility scores.