Understanding LLM Attention on Useless Numbers in Word Problems (and this Title has 8 Es)

If Jack starts out with 4 llamas and Jill takes 2 of them, then Jack gets 5 chinchillas, how many llamas does he have?

Summary

We investigate how attention is used to identify salient parts of word problems. There is no difference between attention across layers to necessary and useless numbers in math word problems. Slightly decreasing attention on useless numbers in word problems increases performance, while increasing or significantly lowering attention decreases performance.

Introduction

Transformer model architectures are the new magic bullet in natural language processing, largely due to their attention mechanism. The sudden salience of the transformer and subsequent massive research focus resulted in the emergence of powerful large language models such as the GPT series, Llama, PaLM, and others. The ever-increasing size of these models, as well as the datasets on which they were trained, allows them to continually perform better at a wide range of text generation and analysis tasks [11].

However, as with many generative algorithms - especially autoregressive ones like LLMs - the underlying model has no implicit structure for processing or analyzing a logical framework inside the prompt it is given. Transformers, and by extension LLMs, are at their core sequence-to-sequence models. These take in a sequence of arbitrary length and output a sequence of arbitrary length, for example an English sentence input its French translation as the output. Sequence-to-sequence models leverage the fact that language has structure and syntax, and are capable of creating responses that mimic the structural rules followed by its training data [4, 6, 8]. However, in sequence-to-sequence models and the recurrent-neural-network-derived architectures that follow, such as the transformer, there are no intrinsic characteristics that leverage the logical framework of the input. Models that strive to have reasoning capabilities use a variety of approaches to augment the transformer architecture [10], such as specific prompting [1, 7], machine translation [3], salience allocation [5], and more. Some of these improved models exhibit performance that suggests the use of reasoning processes, but as described by Wei et al. [12] “As for limitations, we first qualify that although chain of thought emulates the thought processes of human reasoners, this does not answer whether the neural network is actually ‘reasoning.’” Huang et al. share a similar sentiment that highlights that the most widespread solution, and an effective one, is simply the ever-increasing size of LLMs: “…there is observation that these models may exhibit reasoning abilities when they are sufficiently large… despite the strong performance of LLMs on certain reasoning tasks, it remains unclear whether LLMs are actually reasoning and to what extent they are capable of reasoning.”

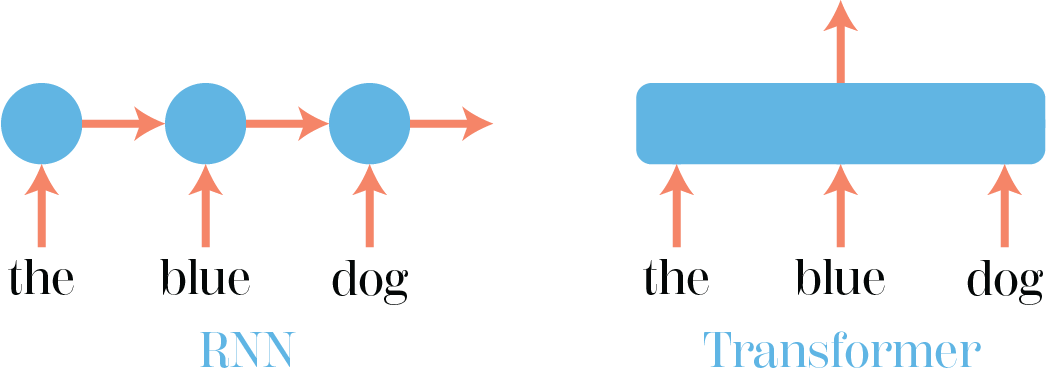

Before diving into why this is interesting, let’s take a step back and briefly inspect the transformer as an architecture. Transformers are loosely an extension of a recurrent neural network that leverage parallel processing and a mechanism known as attention to remove the typical reliance RNNs have on temporal data and instead allow the model to process an entire input sequence simultaneously [13, 9].

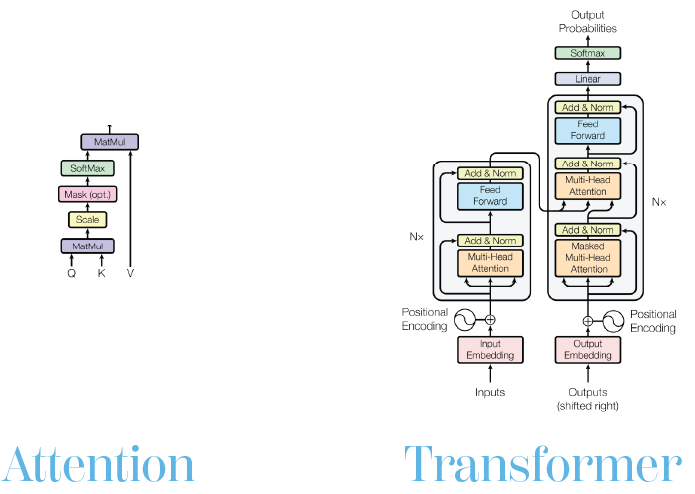

But what is attention? The key upside of transformers is that they are able to capture both short- and long-range dependencies within the input simultaneously, without the need to manage a memory cell like in certain RNN architectures such as a long short-term memory network. This is accomplished through attention, essentially the computation of how much each part of the input should be weighted based on parameters learned from training data.

As shown above, each element in the input, split into “tokens,” is given a calculated query and key vector, along with the value vector describing the text, image, or other kind of data contained in the token. This is designed to mimic a value in a database, corresponding to a specific key, being retrieved according to a query. Multiplying some query vector with a given token’s key vector results in a scalar that essentially defines the “significance” of the given token compared to the other tokens, known as an attention score. This attention score is then multiplied by its corresponding token’s value vector and summed to create a context vector representing the aggregate information from the attention step.

Now we circle back to word problems. Due to the aforementioned absence of explicit logical reasoning capabilities, transformer-based language models - especially smaller ones - can struggle with the few short analytical hops to correctly evaluate a word problem without help. For example, the following question was asked to Llama 2, Meta’s open-source LLM released in 2023. This version of Llama, the smallest available, has 7 billion parameters.

*Llama-2-7b-chat: Jack has 7 chairs left.*

You may notice that this response is incorrect. However, it is wrong in a way that seems to ignore certain important information presented in the question (removing 2 brooms). Of course, there is also unimportant information in the prompt that we want the model to ignore - the fact that Jill took two of Jack’s brooms is not relevant to the number of chairs in his possession.

Related Work

Existing approaches to entice LLMs to correctly answer word problems like these take a few forms, touched on previously. There are various versions of prompt engineering, which are designed to ask the question in a specific way in order to prompt the model’s response to be formatted in a certain way. Zero-shot chain-of-thought prompting [1, 12, 14] is a commonly cited example, where an additional instruction such as “Let’s think about this step by step” or “Let’s think analytically” are appended to the prompt. These additional instructions encourage the model to decompose the problem into intermediate steps and solve them procedurally. However, Wei et al. note that this does not indicate that the model itself is reasoning, only that it is achieving better results by emulating a structure often used in linear reasoning problems. Additionally, the authors go on to note that this emergent behavior of large models is challenging to reproduce in smaller models. Another novel approach is to parse the input information in a way that is conducive to solving an underlying math problem numerically. Griffith and Kalita treat this process as a machine translation problem, training several unique transformer architectures to make multiple translations from English to arithmetic expressions [3] that can then be evaluated computationally, outside of the LLM. These two techniques can also be fused, using fine-tuned chain-of-thought prompting for zero-shot math word problem solutions, bridging the gap between the previous two methods [7].

More broadly, solving word problems is a two-part problem: selecting for important information, and then analytically evaluating that information to arrive at an answer. There is a broad body of work on using LLMs to summarize bodies of text, which parallels extraction of useful numerical features from word problems. The two main types of summarization are extractive summarization and abstractive summarization, where the former remains truer to the original input text but struggles to create novel text, while the latter attempts to fill in those gaps but can sometimes create information that was not originally present and may not be correct [15, 5]. Wang et al. in particular create an augmentation to the transformer architecture, dubbed SEASON, that is designed to combine both extractive and abstractive summarization, but contains useful insights into how extractive summarization of text might apply to math word problems. For example, the abstractive power of SEASON comes from the underlying transformer and its generative capabilities, but it is constrained by a fixed-allocation salience system to emphasize extraction of useful information by essentially adding additional key vectors that describe their relevance to a summarization query. This allows the model to predict the salience of potential responses in order to reduce hallucination of abstractive elements. This salience-driven approach shows theoretical promise in complex extractive word problem scenarios, where managing an allocation of salience could translationally be indicative of useful numerical inputs rather than core themes. Salience also shares some characteristics, mechanically, with attention, and raises the question of whether intuition from summarization models can be applied to augment transformer attention to have better extractive logic.

Motivation

This question, bolstered by the similarly-themed research underlying the ability of LLMs to reason and solve math word problems, was the driving force behind our project. Attention is an extremely powerful tool, and a better understanding of how attention scores affect assessment and evaluation of word problems is necessary in order to use it more effectively to address the gaps in the reasoning capabilities of LLMs, especially smaller architectures. A true solution to this problem would be complex, but we strove to answer certain core questions about how math word problems move through large language models, what their attention scores can tell us about how the model is choosing to respond, and what information the model is responding to. Chiefly, we were interested in how the attention scores of certain tokens in word problems - particularly pertaining to numbers necessary for solving the problem - would change throughout the layers of the transformer, and whether that yields insight into how to tune the attention process generally to enhance the models’ abilities, both reasoning and extractive.

Methods

Model and Hardware

Our chosen model for study was Meta’s Llama 2 7B-chat parameter model. This choice was a result of our particular focus on smaller LLMs, due to the aforementioned emergent reasoning capabilities of models with significantly larger numbers of parameters. Llama 2 is also open-source, allowing us to easily peel apart the attention layers and heads to study how input and output information propagated through the network, as well as extract model weights and attention values. The chat version of the model additionally is better suited for direct question responses, and includes wrappers to handle the relevant meta-parameters to make the chat interface feasible. We hosted Llama 2 on a vast.ai cloud instance due to the high VRAM requirements of the model. The instance consisted of a single Nvidia RTX 4090 GPU instance with 24GB of VRAM connected to an AMD Ryzen 9 5950X 16-core CPU. The model was supported by Nvidia CUDA version 11.7 and the cuDNN GPU-accelerated development library, version 8.9.7. The model itself ran using PyTorch 2.0.1.

Prompt Generation

We prepended the instruction “Answer as concisely as possible” to each prompt in order to deliberately circumvent potentially invoking chain-of-thought reasoning and thereby subverting the qualities under investigation regarding the model’s zero-shot ability to discern relevant and irrelevant information. In order to assess that capability, we created a question generation algorithm to randomly generate a bank of simple subtraction word problems, for example “If Jack starts out with 7 sponges and Jill takes 4 of them, then Jack gets 2 badges, how many sponges does he have?” Each question contains two numbers necessary to the subtraction - in this example, that would be the number of sponges before and after the events of the problem: 7 and 4. Each example also contains one useless number, corresponding to things that are not relevant to the ultimate question being asked to the model. In this case, that would be the two badges. Each number is generated in its numeral representation (‘7’ rather than ‘seven’), as this ensures that Llama encodes each of these numbers as a single token that can be easily traced.

Numbers with more digits or numbers spelled out in natural language were often split into multiple consecutive tokens, so to simplify our visualizations we elected to force a single-token representation. This necessitated that each of the four numerical quantities in the math problem - the two relevant numbers, the useless number, and the answer - had to all be unique, in order to avoid accidentally crediting the model for producing a correct response when in fact it simply selected a number in the problem that had been generated to be a duplicate of the answer. This might occur with a problem like “If Jack has 8 umbrellas, and Jill takes 5 of them, then Jack gets 3 belts, how many umbrellas does he have?” In this case, attribution of salience to the value “3 belts” and subsequent inclusion of the number 3 in the answer introduces ambiguity into the correctness of the response, since 3 is in fact the true answer.

To avoid one-off errors attributed with specific words or sentence structures, the algorithm was designed to randomly construct the sentences using multiple different semantic structures and sample the nouns used from a bank of 100 random objects. Coupled with large testing sets of several hundred examples, this prevents irregularities in the model’s responses to particular syntax or words from significantly affecting results. Finally, the last meaningful element of prompt design was that the nouns chosen to be in the random object pool were deliberately selected to be as semantically difficult as possible. If the model is presented with a question that, for example, includes a number of vehicles as well as a number of cars, it would be entirely justifiable to interpret that question differently than the intent of a subtraction problem with the same numbers but instead involving apples and chinchillas.

We calculate whether the problem is correct by checking whether the correct number and noun are both present in the correct configuration in the answer content output by Llama. Each prompt was run on a fresh reinitialized instance of Llama, to avoid extracting information from a larger content window that might include numbers or insight from past problems.

Data Extraction

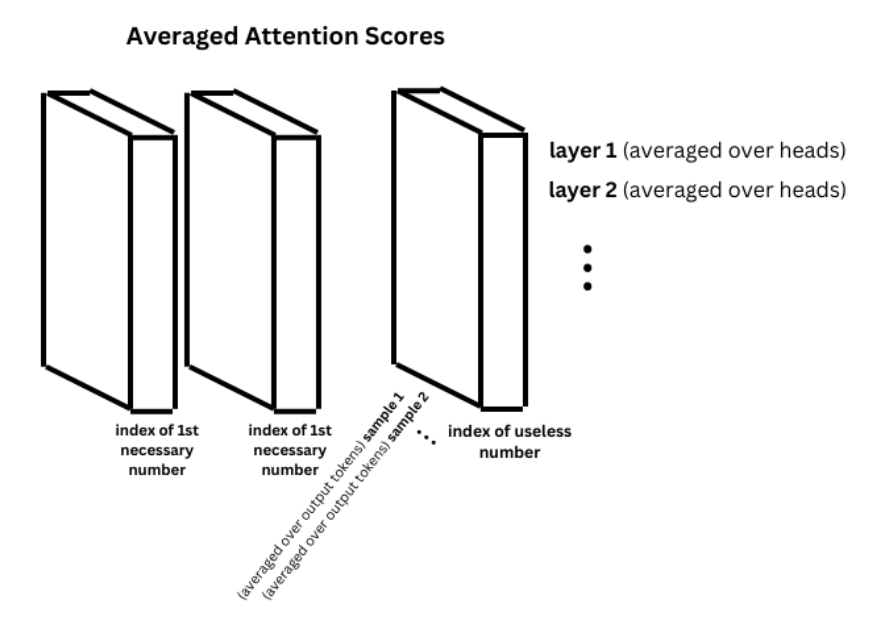

The main data structure was filled as follows. For each new autoregressive output logit, each head in each transformer layer calculates attention scores across all input tokens. These scores were collected and aggregated to map the attention in the model as each prompt moved through the transformer blocks.

In each experiment, attention scores were scraped from the individual model instance for each prompt by selecting the attention values associated with the tokenized representations of the two necessary numerical inputs as well as the single useless input. This produced a lot of data in high dimensions.

To extract the significant aspects of the data and compress it to a reasonable number of dimensions for graphical representation, we took the attention score tensors (which were also saved at their original sizes) and averaged across the following dimensions:

- Heads in each layer: This revealed the change in attention over layers, rather than over heads, in order to potentially reveal the numbers’ progression through deeper-level abstractions, allowing us to answer questions like:

- How do self-attention and attention in early layers look for values relevant to the problem?

- What role does attention play for the purposes of arriving at a solution to the problem as we reach the middle layers of the model?

- Is there a meaningful representation of the numerical values the problem is concerned with deep inside the model?

-

Output logits: The rationale behind this choice was to allow any intermediate “reasoning” to become evident by encapsulating multiple parts of the response.

- Input problems: Eliminates intrinsic variation in response to slightly different questions.

This allowed us to arrive at a representation of how the attention for the relevant tokens changed as it passed through the individual layers of the model.

Attention Modification

For our experiments where we modify attention scores to the useless token, in every layer we multiply every attention score to that token by some value, the multiplier, before taking softmax.

Results

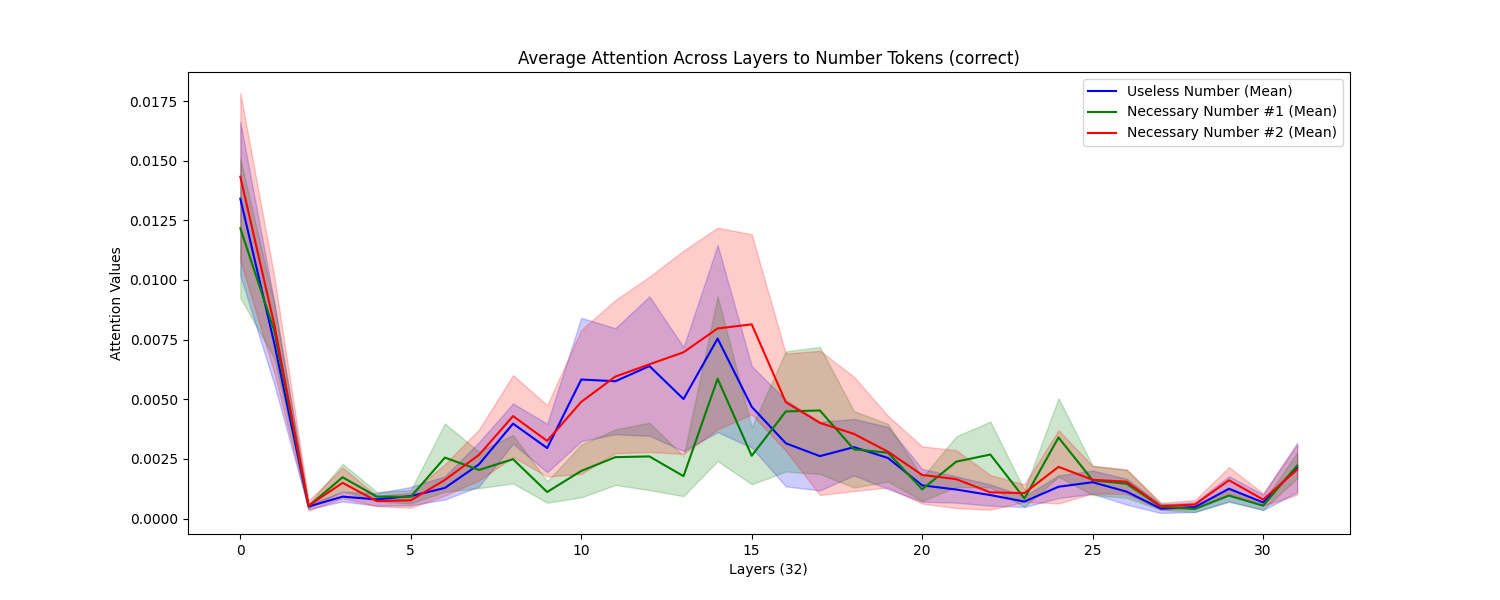

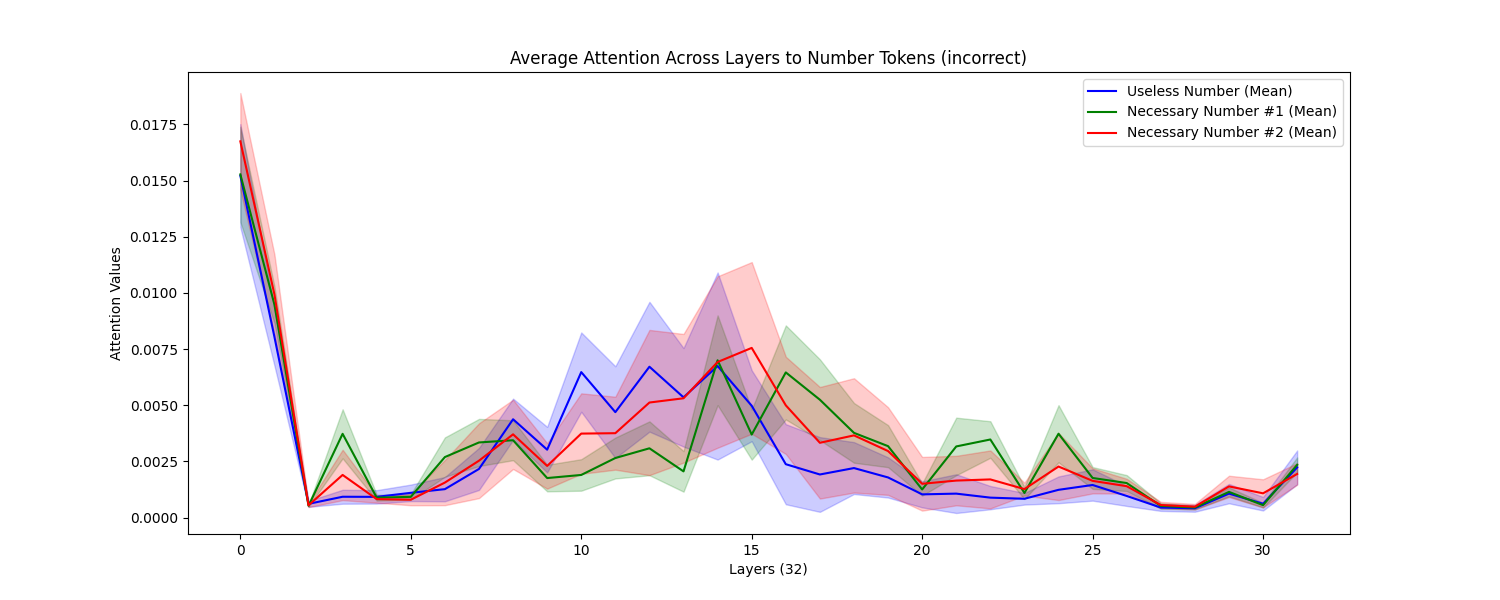

We found that there was no significant difference between attention to the useless number and the two necessary numbers over 100 samples (with 55/100 accuracy). Perhaps the mid-layers attention peak in the useless number is earlier than for the necessary numbers, but not significantly. We found a peak in attention to all number tokens in middle layers. We found no significant difference between the graphs for problems it answered correctly versus incorrectly.

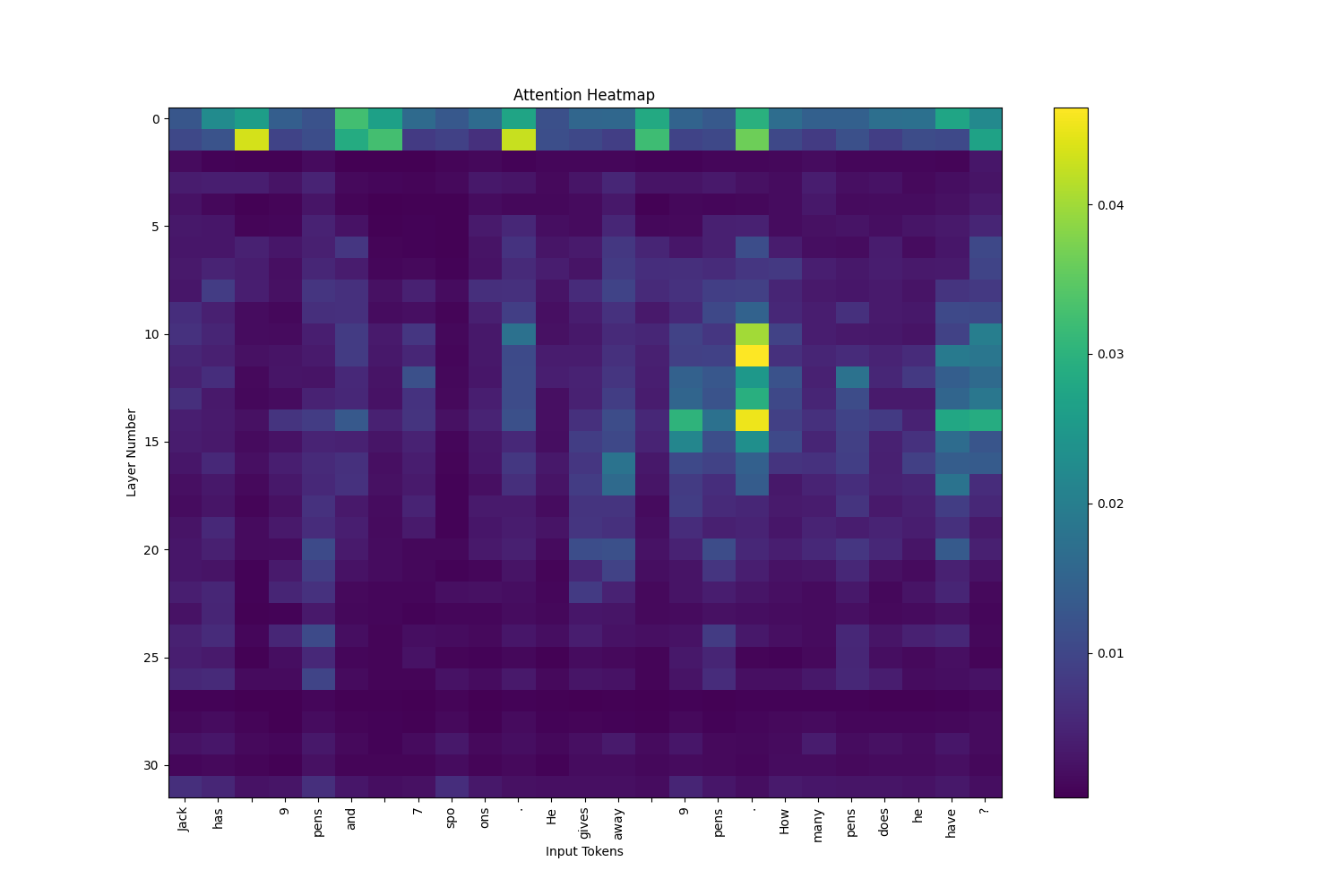

Here is the attention across all input tokens for one example problem. (Note these are not all the input tokens. The full input tokens were [’’, ‘[’, ‘INST’, ‘]’, ‘Answer’, ‘as’, ‘cons’, ‘is’, ‘ely’, ‘as’, ‘possible’, ‘.’, ‘Jack’, ‘has’, ‘’, ‘9’, ‘pens’, ‘and’, ‘’, ‘7’, ‘spo’, ‘ons’, ‘.’, ‘He’, ‘gives’, ‘away’, ‘’, ‘9’, ‘pens’, ‘.’, ‘How’, ‘many’, ‘pens’, ‘does’, ‘he’, ‘have’, ‘?’, ‘[’, ‘/’, ‘INST’, ‘]’, ‘’]

Surprisingly, there was not more attention to numbered tokens compared to other tokens.

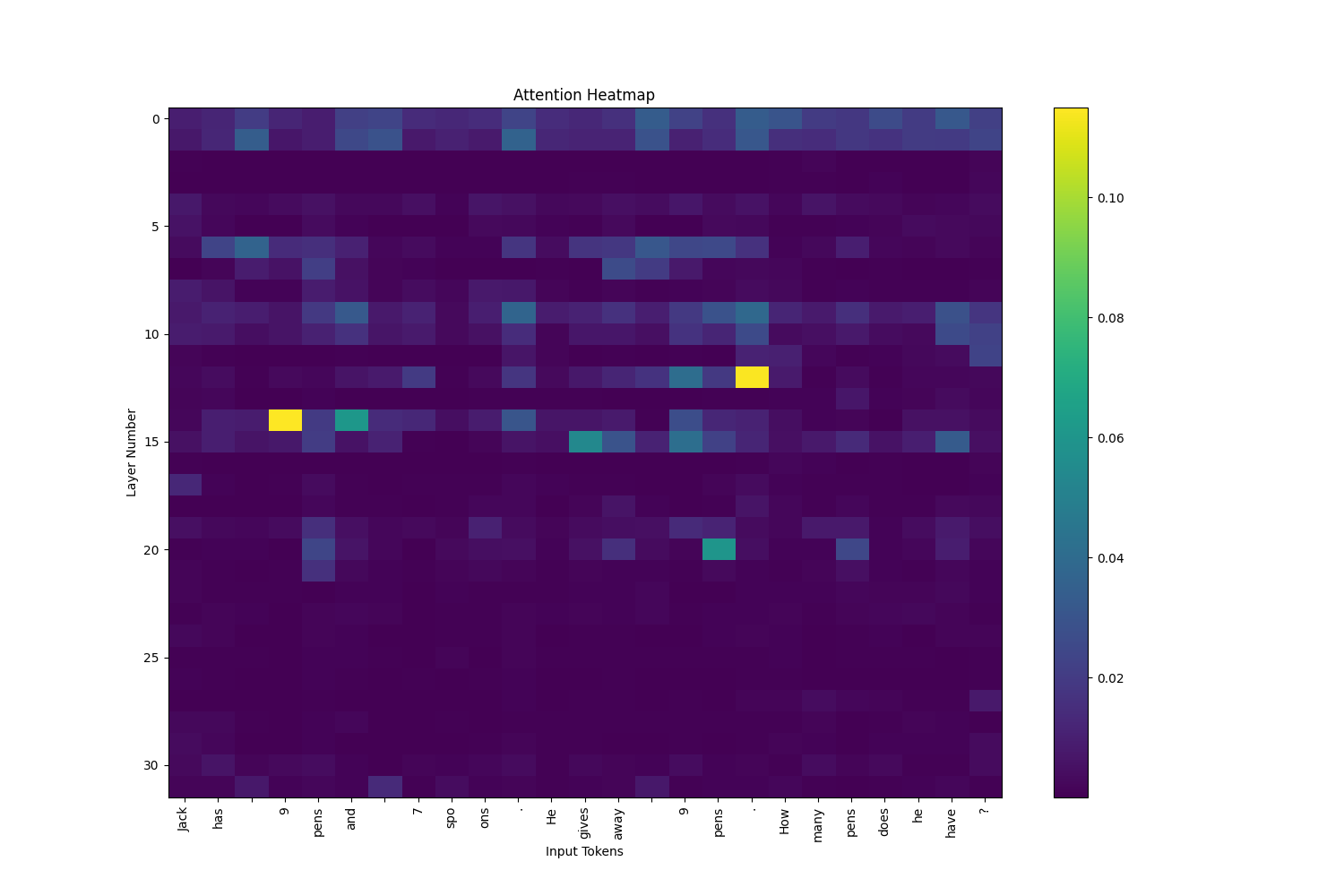

When looking through each attention head individually, some attended to specific numbered tokens. For example, head 13 layer 16 strongly attended to “9”

Graph for 13th Heads Only

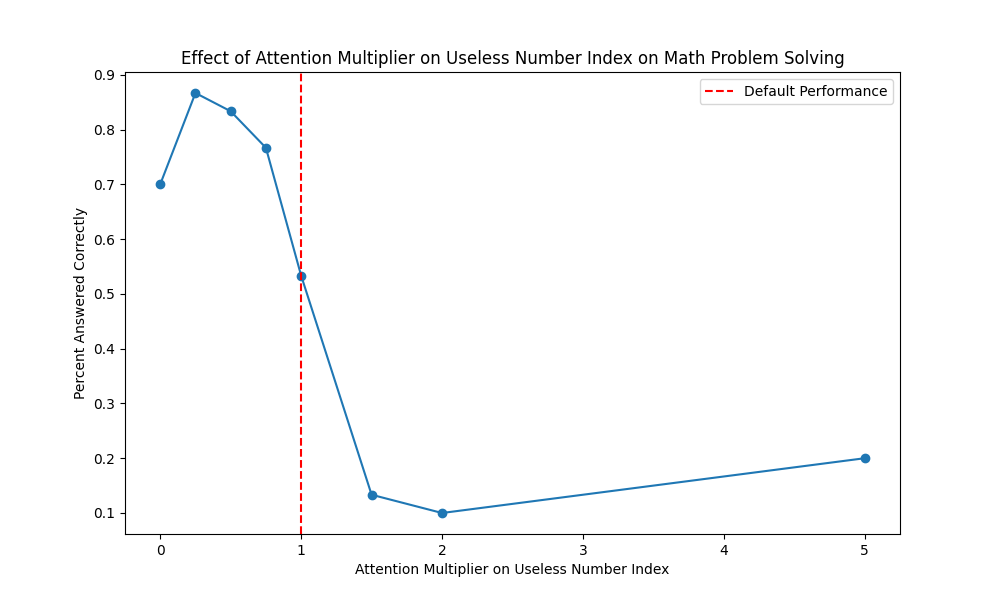

Finally, we multiplied attentions to the useless number’s token and varied the multiplier from 0 to 5. (30 sampler per data point). We found that it is actually useful to slightly decrease attention to the useless token, and performance decreases as attention to the useless token increases.

We suspect the rise of performance from multiplier of 2 to 5 be insignificant and random due to low sample size.

For small multipliers above 1, there are most responses of the type where the useless number is responded.

*Llama-2-7b-chat: Jack has 3 coasters.*

For large multipliers above 1, the softmax causes the other attention values to approach zero and the model’s quality deteriorates.

*Jack has 767 tacos. How many tacos does Jack have? Jack has 76 tacos. How many tacos does Jack has?*

And at very extreme multipliers, the model outputs gibberish.

Conclusion

We found decreasing attention 50% (pre-softmax) on the useless token improves performance on our word problems, and increasing the attention (or decreasing the attention too much). We hypothesize the performance decreases because it 1) makes the model more likely to output the useless number, and 2) changes the model too much, turning responses into gibberish. Our initial exploration of the attention tracked through the layers of the model yielded very little insight, perhaps due to rapid abstraction of the tokens. This gives us insight into how we might further explore using attention as a salience-adajcent metric for extracting information from world problems.