Modeling Human Speech Recognition with Different Network Architectures

Evaluating a neural network's ability to effectively model human speech recognition using CNNs vs. TNNs

Introduction

Recent advances in machine learning have made perception tasks more doable by computers, approaching levels similar to humans. In particular, structuring models biologically and using ecologically realistic training datasets have helped to yield more humanlike results. In the field of speech recognition, models trained under realistic conditions with stimuli structured how sounds are represented in the cochlea, with network layers imitating the processing pipeline in the brain, seem to be successful in performing speech recognition tasks. However, it is unclear whether specific network architectures are more beneficial to learning human speech recognition patterns. In this project, I seek to investigate how different network architectures such as CNNs vs. TNNs affect the ability to recognize speech in a humanlike way.

One facet of more biological models is that they attempt to recreate the structure of the human brain. For auditory models, a useful structure to replicate is the cochlea; these replications are called cochleagrams. Cochleagrams have been used in order to model the ear more effectively, leading to models that imitate auditory perception in a more human-like way. A cochleagram works in a similar way to how the cochlea works in a human. It filters a sound signal through bandpass filters of different frequencies, creating multiple frequency subbands, where the subbands for higher frequencies are wider, like how the cochlea works in the human ear. The amplitudes of the different subbands are then compressed nonlinearly, modeling the compressive nonlinearity of the human cochlea

A recent application of cochlear models to speech perception is found in Kell’s 2018 paper, where they create a convolutional neural network which replicates human speech recognition

A natural question to ask at this point is whether a convolutional neural network is the best architecture for this task. In Mamyrbayev Orken et al.’s 2022 paper, they explore a speech recognition system for Kazakh speech

In the field of computer vision, there has been work done comparing convolutional neural networks to vision transformers for the task of object recognition. Tuli’s 2021 paper explores this through the lens of human-like object recognition, determining whether the errors of a vision transformer or a convolutional neural network are more similar to humans

In this post, I investigate more closely the importance of network architecture in the ability to effectively model human speech recognition. I focus on three metrics of evaluating how well a model replicates human speech recognition:

- Ability to generalize to speakers not found in the training set: Humans hear speech from new speakers all the time, and a person who they’ve never heard before usually does not hinder their ability to recognize what they are saying. Models of speech recognition are usually trained on a corpus of speech that is inherently biased towards a set of talkers that participates in creating the corpus, so it is possible that it could overfit to the speakers in the training set. A good model of speech recognition should be able to perform well on new talkers.

- Ability to recognize speech in different background noise conditions: Humans rarely hear speech unaccompanied by some form of background noise, and are generally robust to noise up to large signal to noise ratios. Many models of speech recognition such as the transformer in Orken 2022 are not trained or tested on noisy speech, so it is likely that it would not be able to recognize speech in these conditions.

- Ability to recognize distorted forms of speech: Humans are remarkably robust to various distortions of speech such as sped-up/slowed-down speech, reverberant speech, and local-time manipulations, despite not encountering some of these often in their lives

. In order to further test a model’s ability to replicate human speech recognition, we should test how well it performs on speech manipulations.

Methods

The models in my experiment were given a 2 second speech clip, and were tasked with identifying the word overlapping the middle of the clip. In particular, they were trained on a dataset containing 2 second speech clips from the Common Voice dataset, where the word at the middle of the clip is from a vocabulary of 800 words, imposed on different background noises taken from the Audio Set dataset

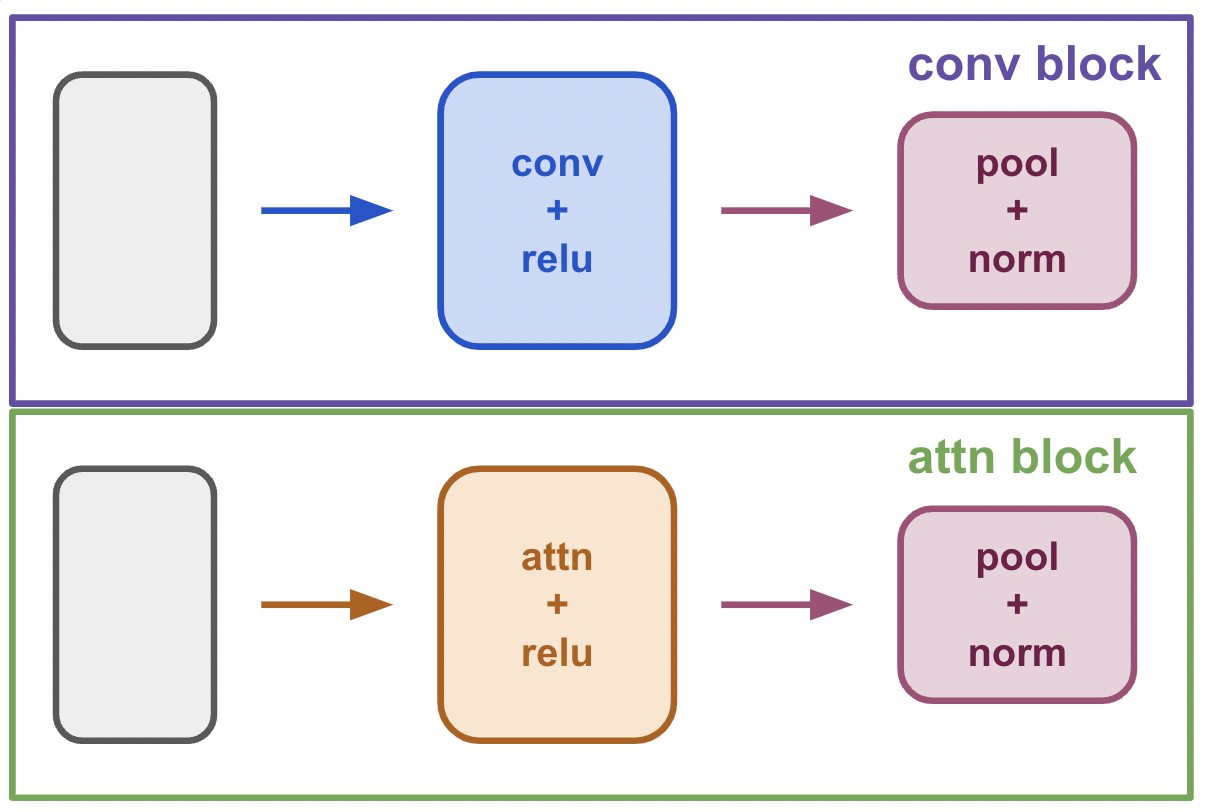

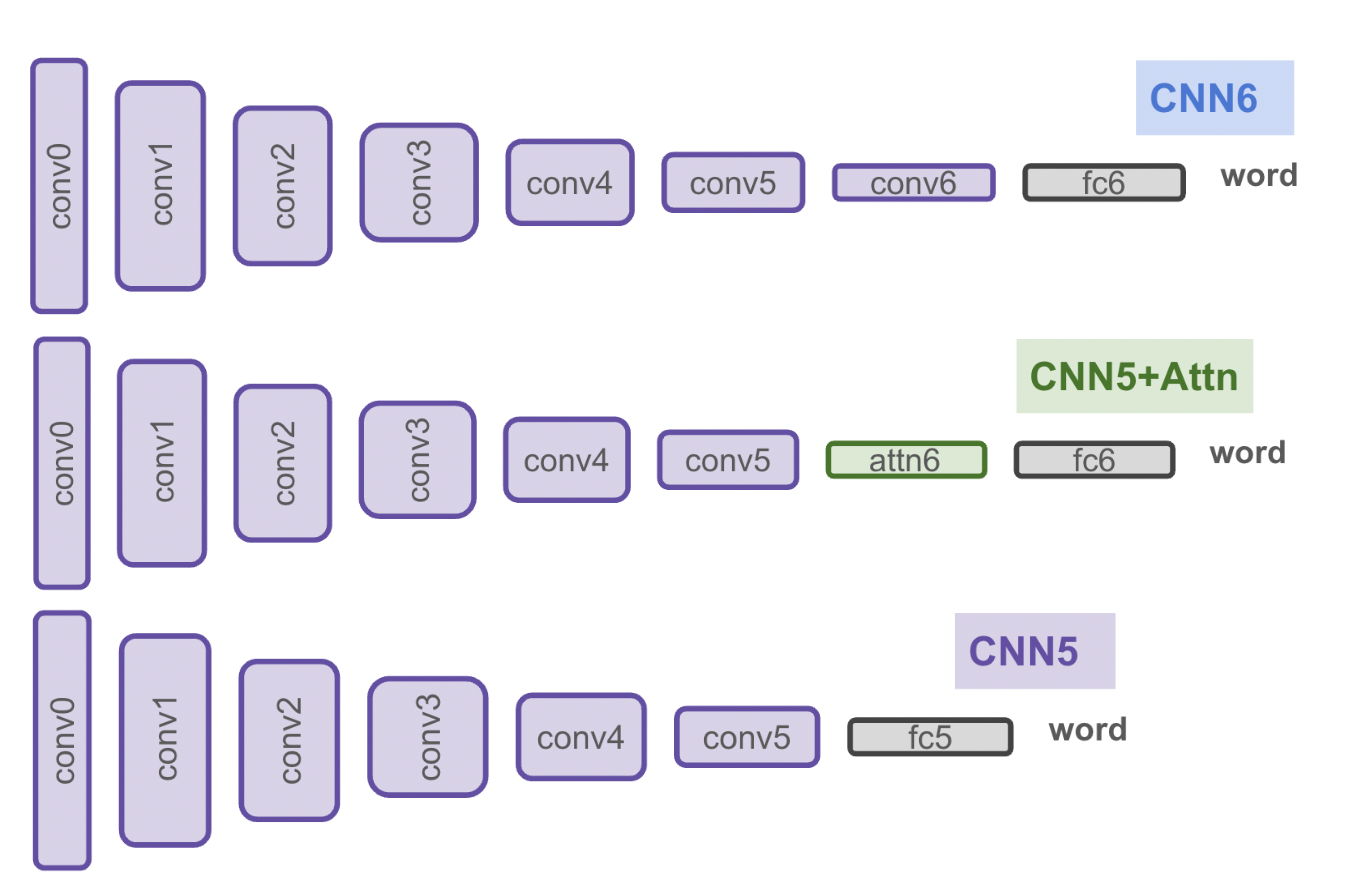

In order to generate the fairest comparison between convolutional neural networks and transformers, I start with a baseline CNN inspired by Saddler 2021, and then either replace the last convolutional layer with a multi-headed attention layer or remove it from the network

The baseline CNN (called CNN6) is composed of 6 blocks followed by a fully connected layer and a classification layer. The transformer-CNN hybrid (CNN5+Attn) is composed of 5 convolutional blocks, followed by an attention block, followed by a fully connected layer and a classification layer. Lastly, I created a “control” CNN (called CNN5) that is the same as CNN6, but with the last convolutional block removed. This was intended to test whether an attention layer provides any benefit as opposed to not including the layer at all. All networks begin with an initial data preprocessing step that converts the audio signal into a cochleagram.

It is difficult to derive a direct comparison between a convolutional layer and a multi-headed attention layer, in particular how to decide how many attention heads to include and what the attentional layer dimension should be. In order to have the best chance of comparison between CNN5+Attn and the other networks, I ran multiple CNN5+Attn networks with a larger vs. smaller number of attention heads (64 vs. 16) and a larger vs. smaller attention dimension (512 vs. 16) for 10 epochs to determine a preliminary measure of network performance across these parameters. The preliminary results after 10 epochs showed that the CNN5+Attn network with a small number of attention heads and a smaller attention dimension had the highest training accuracy and trained the fastest, so I used this model for my analysis.

After preliminary analysis, I trained the CNN6, CNN5+Attn, and CNN5 networks for 100 epochs. I then evaluated the models’ performance on this task in the three aforementioned conditions.

1) To evaluate performance on clips spoken by talkers not encountered in the training dataset, I evaluated the models on clips taken from the WSJ speech corpus.

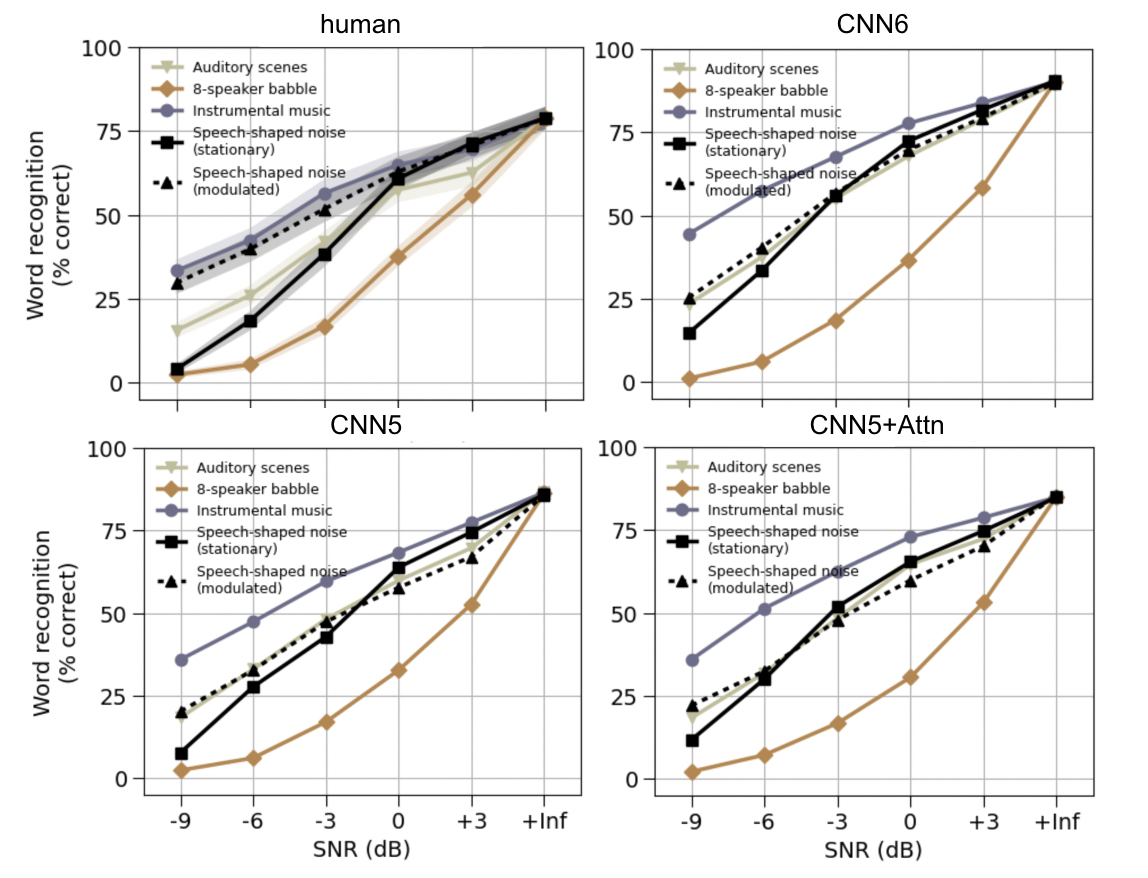

2) For clips superimposed on different types of background noise, I evaluated the model on 5 types of background noise, in signal-to-noise ratios ranging from -9 dB to +3 dB, plus a +infinity condition which represents no background noise:

- Auditory scenes: background noises encountered in everyday life like rain or cars passing by

- 8-speaker babble: 8 other people talking in the background

- Music

- Speech-shaped noise: gaussian noise that is given the envelope of speech signals

- Modulated speech-shaped noise: speech-shaped noise that is modulated so that the noise alternates between being very quiet and very loud

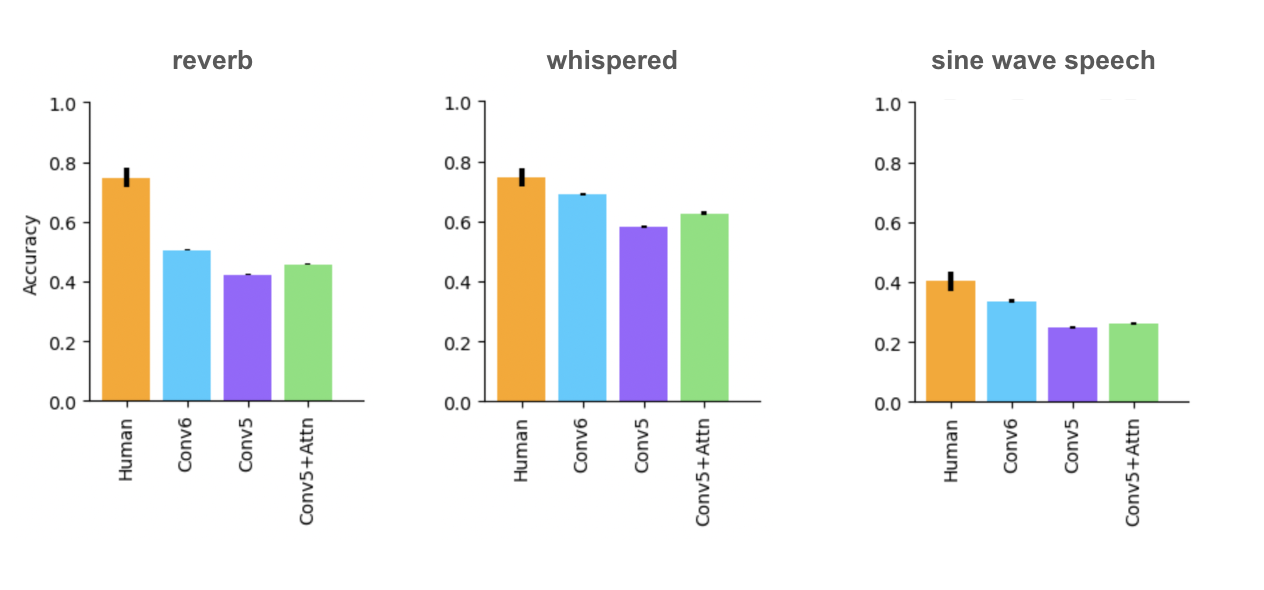

3) Distorted speech clips with 6 types of distortions:

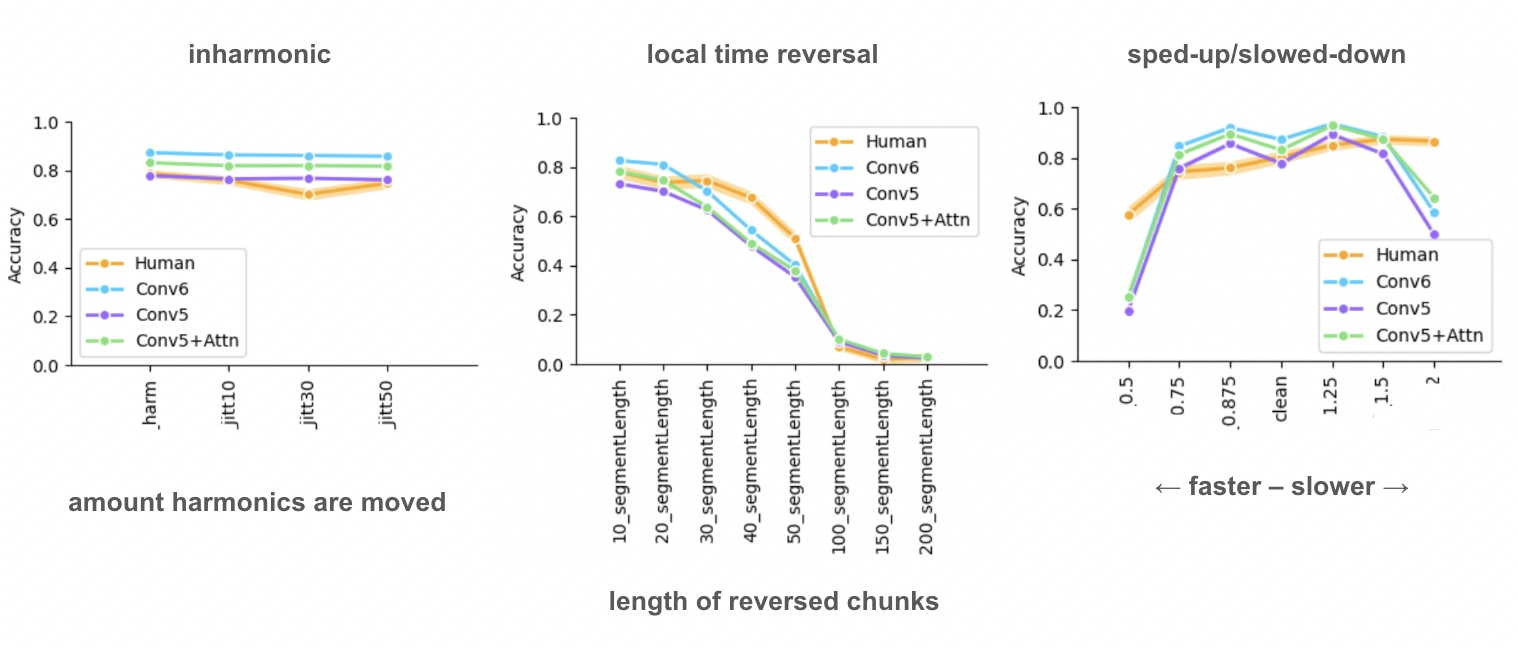

- Sped-up/slowed-down speech (preserving original pitches)

- Speech in a reverberant environment: speech convolved with an impulse response of different reverberant environments

- Whispered speech

- Inharmonic speech: speech signals are decomposed into their harmonics, and the harmonics are moved up or down to distort the signal

- Sine wave speech: speech signals are filtered into frequency subbands, and each band is replaced by a sine wave with the center frequency of the band

- Locally time-reversed speech: speech is decomposed into chunks of a certain length, and the chunks are reversed

Then I compared the models’ performance on these conditions to existing human data where humans were asked to perform the same task of recognizing the middle word of a 2-second clip in various types of noise or distortion.

Results

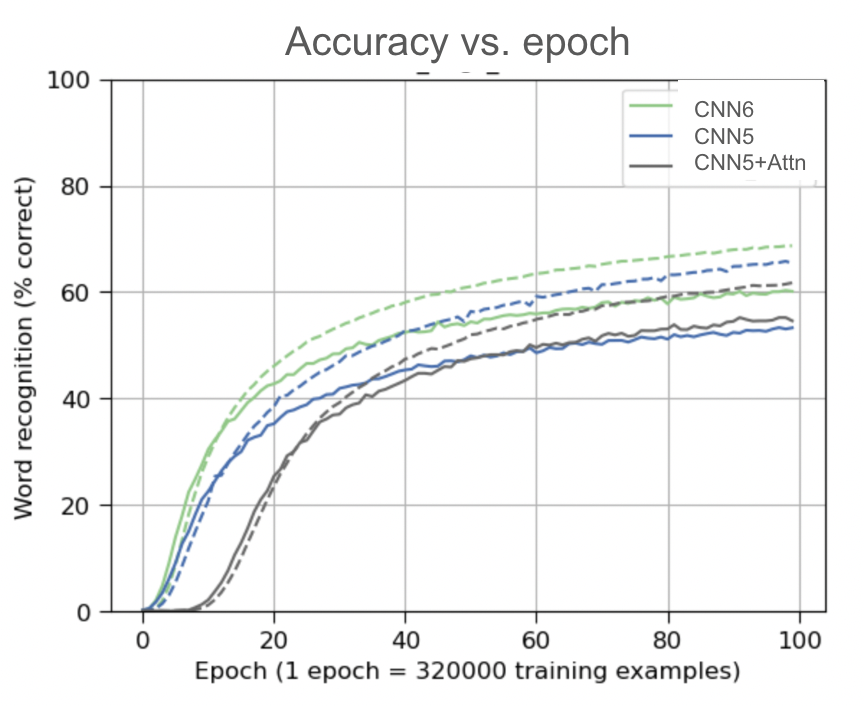

Overall, I found that CNN6 performed better than CNN5+Attn, which performed better than CNN5. After 100 epochs, CNN6 had a validation accuracy of around 0.60, CNN5+Attn had validation accuracy of 0.55, and CNN5 had validation accuracy of 0.53. In particular, CNN5 overfit quite a bit (0.12 gap between training and validation accuracy) while CNN5+Attn overfit much less (0.05 gap between training and validation accuracy).

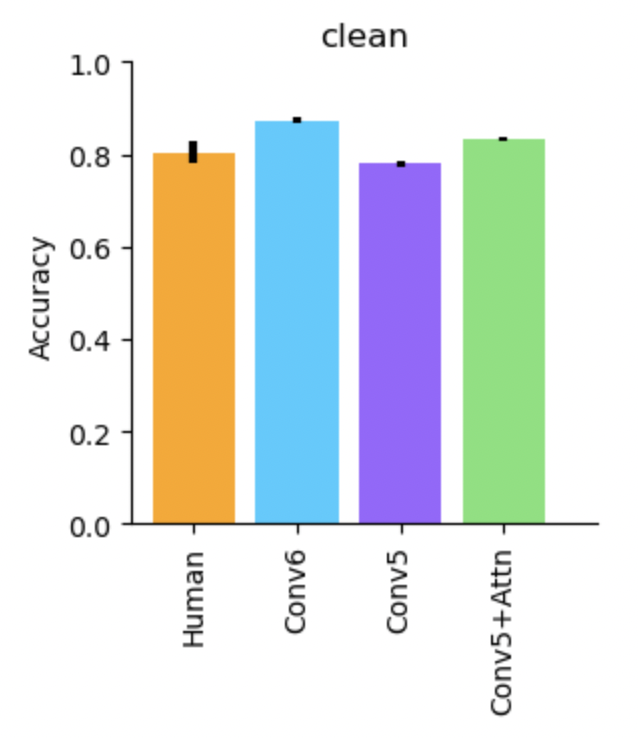

All three models performed similarly to humans for clean speech spoken by talkers not encountered in the training dataset.

In different types of background noise, in general the models performed similarly to humans, except in the condition of modulated speech-shaped noise. In general, humans perform better for modulated noise than “stationary” noise because they are able to fill in speech in the “gaps”, or quieter sections, of the noise, but none of the models have as strong of an effect as humans for this. The CNN5+Attn model does particularly badly on this compared to the other networks.

The models all perform similarly to humans for inharmonic speech, local time reversal, and low levels of sped-up or slowed-down speech. For whispered speech and sine-wave speech, the models perform slightly worse than humans, with CNN6 performing better than CNN5+Attn performing better than CNN5. For reverberant speech and extremely sped-up or slowed-down speech, all of the models perform significantly worse than humans, with the same hierarchy of performance between the models.

Discussion

Overall, it seems that CNN6 is the best option for replicating human speech recognition, but CNN5+Attn does have some benefits. In particular, it trains substantially faster than CNN5, and overfits less than both CNN5 and CNN6. The hybrid architecture may help with overfitting because it forces the model to do multiple types of analysis in order to determine the output. Although CNN5+Attn does still perform worse than CNN6, it is reasonable to hypothesize that it has potential. Due to resource limitations, I was only able to test two different conditions for number of attention heads and attention dimension, but as shown from the preliminary training the number of attention heads and the attention dimension does have an effect. It seems likely that with a more extensive search of these parameters, it could be possible to create a CNN5+Attn network that performs similarly or better than the CNN6 network on these tasks.

All of the models have discrepancies with humans for the modulated background noise condition. One possible explanation for this is that the models do not learn the process of recognizing smaller phonemes of a word, only learning a classification task on the 800 words that they are given, so they are unable to piece together chunks of a word into a larger word like humans do. A possible way to test this would be to create a model for a phoneme-detection task, and then add a layer that combines the phonemes into a larger word, and see whether this performs better in this condition. This would make sense because some of the earliest things humans learn about speech are not full words, but phonemes like “ba” or “da,” so a model trained on this task would then have been optimized in more human-like conditions.

In addition, there are some discrepancies between the models and humans in some of the speech distortions. The largest discrepancies are found in very sped-up or slowed-down speech, and in reverberant speech. This seems likely to be due to a shortcoming of the dataset. The Common Voice dataset is composed of people reading passages, which is generally a single slow, steady speed, and there is no reverberation. The speech that humans encounter in their lives varies a lot in speed, and they also encounter speech in many different reverberant environments, so they are optimized to recognize speech in these conditions. It is reasonable to assume that if reverberation and varied speeds of speech were incorporated into the training dataset, the model would perform better in these conditions.

Further directions of this project could include trying more variations of the parameters of the attention model. In addition, it would be interesting to try different hybrid architectures; for example, 4 layers of convolution followed by 2 layers of attention. This could give a more complete idea of the benefits and disadvantages of CNNs and transformers for the task of speech recognition. In conclusion, the current results seem promising, but more extensive testing is needed in order to get a full picture of whether these models can accurately replicate human speech recognition.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my fellow members of the McDermott Lab, particularly Mark Saddler for creating the code for the baseline CNN, and Erica Shook for providing me with human data and experimental manipulation code.