Improving CLIP Spatial Awareness Using Hard Negative Mining

CLIP struggles to understand and reason spatially. We attempt to solve this issue with introducing hard negative examples during training.

Introduction: CLIP doesn’t know its left and rights

Multimodal learning has come into prominence recently, with text-to-image synthesis models such as DALLE or Stable Diffusion, and image-text contrastive learning models such as CLIP. In particular, CLIP has proven to be extremely useful in learning zero-shot capabilities from paired image and text data.

However, recent work has highlighted a common limitation in multimodal models: the ability to capture spatial relationships. Spatial relationships can be defined as how objects in an image are positioned concerning other objects. For example, A is next to B or B is on top of A. Although Language models now demonstrate an understanding of word order and spatial awareness, multimodal models still struggle to capture this relationship in both the image and captions.

Downstream tasks

Improving captioning abilities is an important building block in overcoming this limitation in all multimodal models. Creating synthetic captions from images is an already popular method in developing training data for other models such as DALLE-3. However, limitations in captioning abilities carry over to downstream tasks, and therefore, models such as DALLE-3 often also struggle to generate images from prompts that include spatial relationships. We hope that demonstrating the ability to generate spatially-aware captions will also lead to improvements in other Vision-Language models in the future.

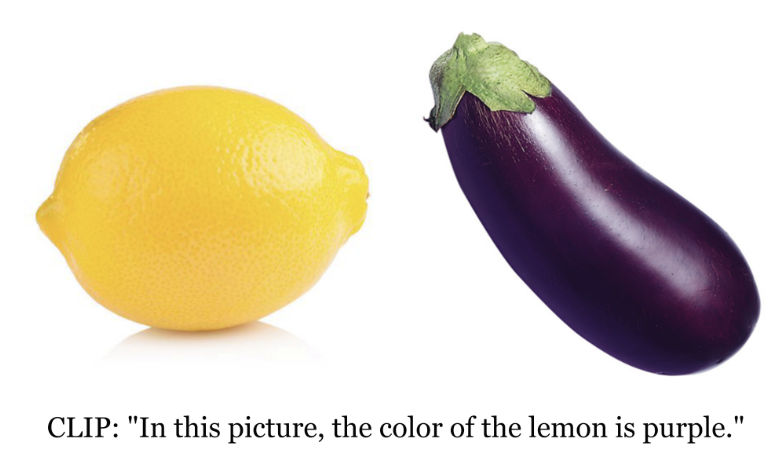

Semantic similarity

CLIP is trained to maximize the similarity between embeddings of images and text. This leads to CLIP matching semantically similar images and captions but not understanding finer-grained details. Concept Association is especially an issue when there are multiple objects in an image where CLIP struggles to reason about the object’s attributes (Yamada 2022). Additionally, because of the focus on semantic similarity, CLIP also struggles with spatial relationships between objects.

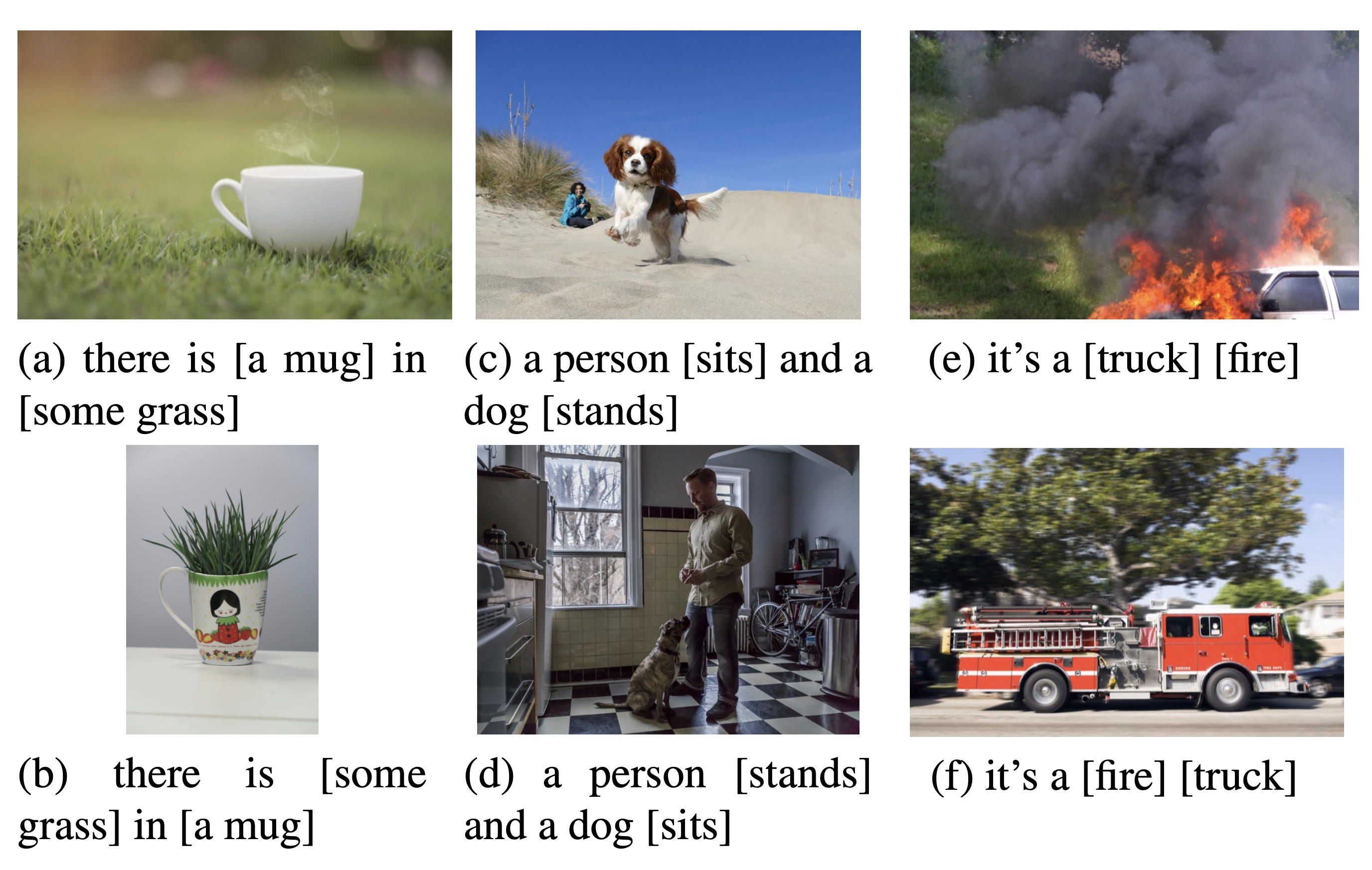

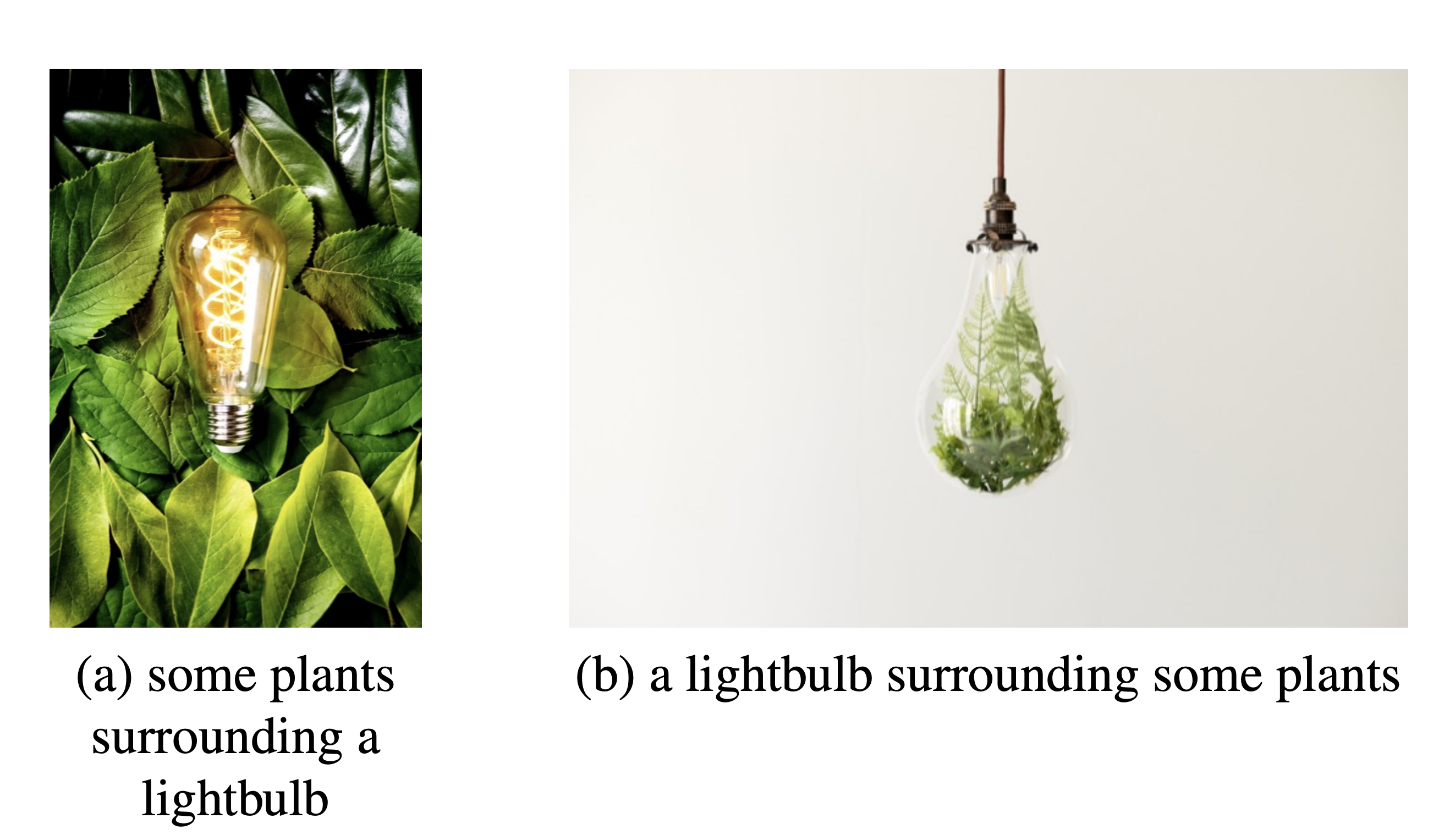

Winoground

Spatial awareness has been explored explicitly throughout previous literature. Thrush et al. in Winoground created an evaluation dataset that targets compositional reasoning. Each data point contains two captions and two images, where the captions contain the same words only in different orders. The difference in word ordering drastically changes the meaning of the sentence and therefore the image associated with the alternative caption also is completely different. The task then becomes to match the images to the correct captions (Thrush 2022).

Evaluation Specifics and Results

We are going to use the image-to-caption evaluation of Winoground which aims to match captions to each image in constrast to images to captions. Different models have differnt matching strategies; CLIP uses the higher dot product similarity score when deciding which caption fits each image. Since there are in total, 4 different possible matchings out of the 2 image/caption pairs, random chance would score 25%. However, many multimodal models fail to score much higher than random chace. CLIP (ViT-B/32) scores 30.75% while the best models only score 38%.

Spatial Examples

CLIP has shown to be an extremely difficult benchmark for multimodals - and there are multitude of reasons why. First, changing the word orders creates image/caption pairs that need fine-grained reasoning capabilities to differentiate. One of the many reasoning capabilities needed to do well is spatial reasoning. We filter out 101 examples of CLIP that contain image/captions that require spatial reasoning to create a more task-speciific benchmark. Our filtering is caption-based and targets key words that may indicate spatial relationships. We will refer to this filtered out evaluation benchmark as, Winoground-Spatial.

Hard Negative Examples

Hard negative examples are negative examples that are close to our anchor pair. These are examples that are close in some way to our positive example, but still wrong. Oftentimes, these examples are hard to distinguish from one another, and therefore cause the model trouble.

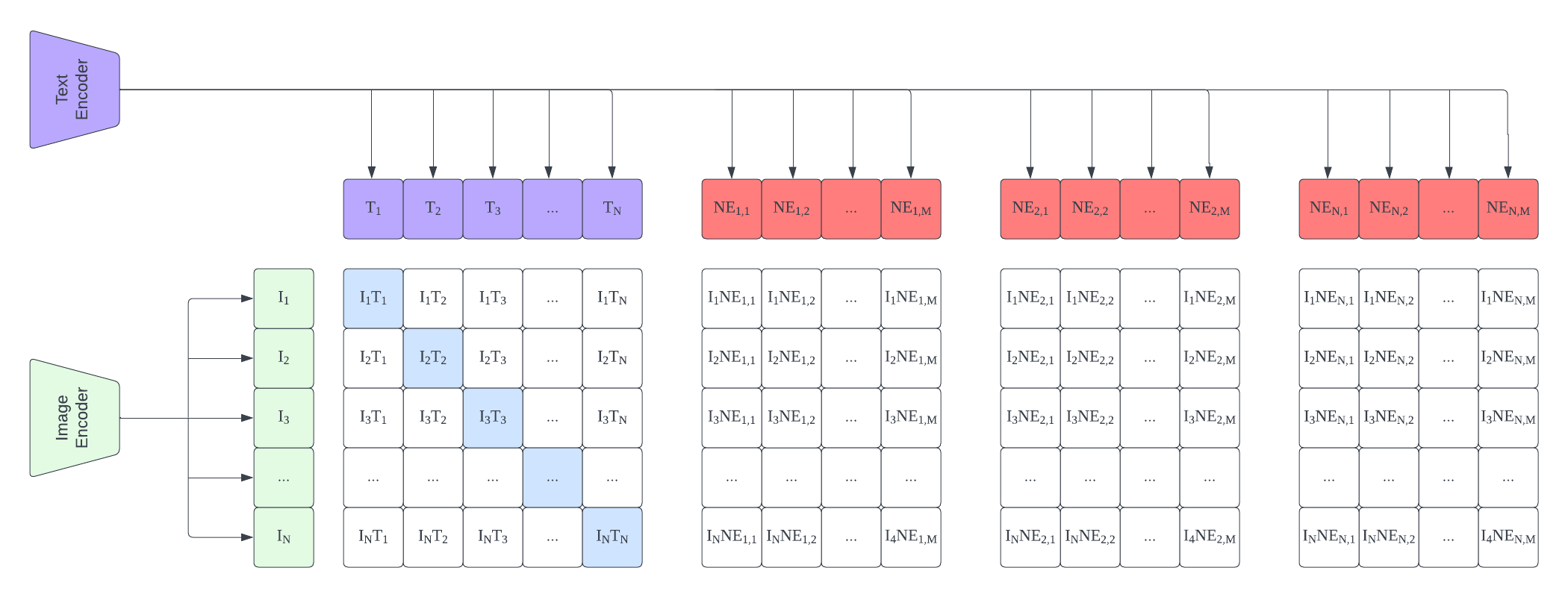

CLIP Loss

As a refresher on how CLIP is trained, CLIP first calculates an N by N similarity matrix from the dot products of the two embeddings. The model the calculates a loss function as the average of two cross entropies. The task becomes a classification task where we classify the correct caption for each image and the correct image for each caption, thus leading to two cross entropy functions.

We modify this training procedure to include additional hard negative captions. For each image/caption pair, we generate M additional negative captions. We then calculate an N by NM similarity matrix from the dot products. Then, we only modify the loss function for image classification cross entropy function to include negative captions alongisde the original N captions. We don’t modify the caption classification cross entropy function since the negative examples don’t have a corresponding “image”.

Data and Augmentation

How do we generate negative examples? We first have to create a fine-tuning dataset that contains image/caption pairs that display spatial relationships. To do this, we utilize the dataset Flickr30k, a dataset that contains 31,000 images collected from Flickr along with 5 captions annotated by human annotators. We chose this dataset due to it’s caption quality alongside the fact that many of the image/caption pairs contain multiple objects.

We then filter out image/caption pairs based on the captions in a similar way we created our evalutation benchmark, Winoground-Spatial. We use 20 key words and phrases such as: “left”, “on top of”, “beneath”, etc. to create a training set of roughly 3,600 examples. Although there are most likely more spatial examples, we choose this method as it is cost-effective while still ensuring the quality of the traning set being only examples of spatial relationships.

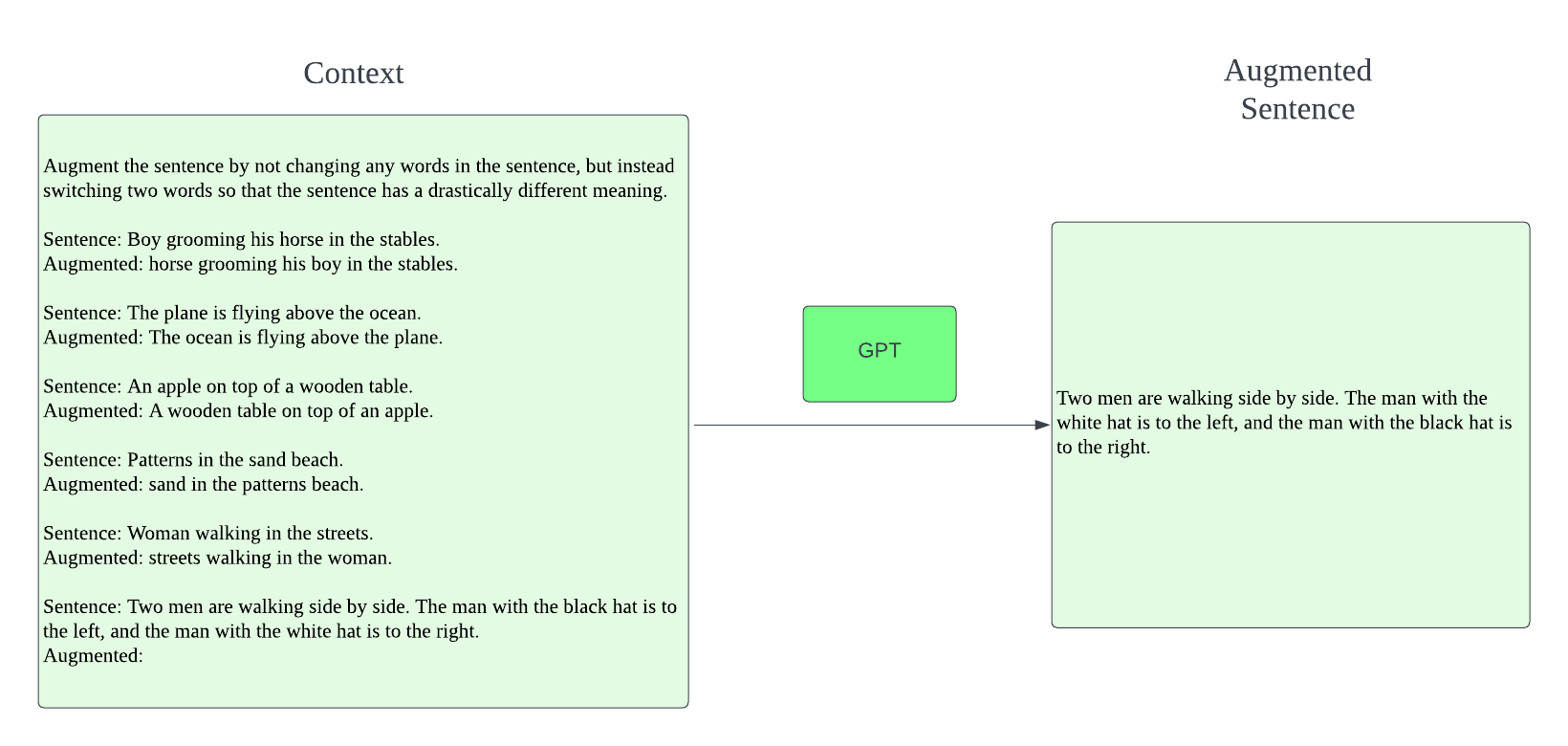

Data augmentations have been a commonly used as a method to prevent overfitting in image classification tasks. Although it is common to perform image augmentations, Fan et al. introduce LaCLIP to perform text augmentations on captions to create additional image/caption pairs. This method can be thought of as generating additional “positive pairs”. In order to generate text-augmentations, they utilize language models such as llama7b and GPT-3 to ensure the sentences generated are still grammatically correct. They use in-context learning and prompts such as, “Rewrite this caption of an image vividly, and keep it less than thirty words:”.

We follow a similar procedure to generate our negative examples. For each image/caption pair, we prompt GPT-3.5-turbo-instruct to do different augmentations. Details of the prompts are provided in the later experiments.

Experiments

For all experiments, we use a base model of CLIP(ViT-B/32) pre-trained on OpenAI’s WIT provided by OpenClip. We then use OpenAI’s API to generate augmentations. In total, the cost of generating augmentations were under $50 in credits.

Experiment 1: Switching word order

Our first experiment explores how switching the word order may serve as hard negative examples. This method is inspired by the benchmark we are using, where the captions share the same words but in a different order. For each caption, we generate a single hard negative caption. The prompt we use is displayed below:

We discover adding a single hard-negative example to each example already leads to an impressive performance boost. The accuracy improves from 19.8% to a staggering 50.5% from fine-tuning.

| Pretrained CLIP | Word Order CLIP | |

|---|---|---|

| Pairs matched correctly | 20 | 51 |

| Accuracy | 0.198 | 0.505 |

We did some extra probing and noticed the majority of the improvement was from distinguishing left and right. From the additional 31 examples our fine-tuned model got correct, 18 of them were examples that the captions included the keyword of either left or right. This is consistent with our training set, where the most popular keyword of our examples is left/right.

Experiment 2: Replacing key spatial words

We then explore how a different augmentation workflow could impact the accuracy. In this experiment, we augment the captions to replace the keyword with another spatial keyword. For example, the keyword “on top of” could be replaced by “underneath” or “to the right of”. We again, utilize GPT to ensure the captions are still grammatically and logically correct. Because of the number of keywords avaialable, we explore how the number of negative examples during training time may affect the model’s accuracy.

| 0 negative examples (Pretrained CLIP) | 1 negative examples | 5 negative examples | 10 negative examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairs matched correctly | 20 | 31 | 65 | 55 |

| Accuracy | 0.198 | 0.307 | 0.644 | 0.545 |

We can notice that from 0-5 negative training examples, there is a distinctive increase in model accuracy. However, an interesting result is the dropoff in accuracy from 5 training examples to 10. We did some probing into why this may be the case in the training data. One hypothesis may be the training examples for hard negatives are incorrect, in that, by a human they could be interpreted as positive examples. For example, object A could be both next to and above object B, but we are training CLIP to recognize the keyword above to be false in this case. Another hypothesis is the difficulty in training examples stunting training and needing more data. This could be case when looking at the loss function, on whether it has fully converged or not.

Conclusion and Limitations

Although we have not fully tackled the issue of spatial awareness, we have made signifigant progress from our base model of CLIP, with the highest accuracy being at 64.4% compared to 19.8%. This proof of concept work shows how hard-negative examples could boost improvements in specific reasoning tasks. The concept of using these hard-negative examples are not limited to spatial relationships: it could be interesting to examine how hard negative tasks may improve other Winoground examples that require reasoning capabilities such as counting. We also note that there is a possiblity that improving the training data may not be enough, and that the architecture may need a change to fully solve spatial relationships.

References:

1.Robinson, J. D.; Chuang, C.-Y.; Sra, S.; Jegelka, S. Contrastive Learning with Hard Negative Samples. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

2.Thrush Tristan, Jiang Ryan, Bartolo Max, Singh Amanpreet, Williams Adina, Kiela Douwe, and Ross Candace. 2022. Winoground: Probing Vision and Language Models for Visio-Linguistic Compositionality. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 5238–5248.

3.Fan, L., Krishnan, D., Isola, P., Katabi, D., and Tian, Y. (2023a). Improving clip training with language rewrites. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.20088.