Solvent Encoding for solubility prediction using GNN

Evaluation of different solvent-encoding methods on a public available solubility dataset

Introduction

Solubility serves as an essential descriptor that models the interaction between molecules and solvents. This property is important for many biological structures and processes, such as DNA-ion interactions and protein foldings. Quantum mechanics-based approaches, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), have been deployed in multiple attempts to model solubility across diverse systems and temperatures. However, the complex nature of the problem makes it computationally demanding to accurately predict the properties with fast speed. The development of QSPR(Quantitative structure-property) and deep graph neural network enables us to explore the chemical space with significantly lower computational costs by modeling molecules as graphs and treating properties prediction problems as regression problems. Yet, the challenge persists—individual molecules do not exist in isolation. Due to the strong interaction between molecules, the existence of other molecules(solvent, in particular) in the environment can strongly impact the property we want to predict. However, most of the existing GNN models can only take one molecule per input, limiting their potential to solve more general chemical modeling problems. As a result, it is important to incorporate solvent embedding into the models. The focus of the project is to augment existing GNN models with various solvent-encoding methods and evaluate the performances of different models on a publicly available solubility dataset. My goal is to find out the best encoding method and potentially compare the performances of different models on various solubility datasets.

Implementation

This project intricately explores the functionalities of Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based models, focusing specifically on chemprop and PharmHGT. These models have exhibited remarkable proficiency in predicting molecular properties through a diverse array of message-passing and readout functions. The transformation of solvent smiles strings into feature vectors is executed through two distinctive methods. The initial approach involves the conversion of solvents into various descriptor vectors, while the second method treats solvents as independent graphs, applying GNN models to capture their inherent structural nuances.

Following this encoding phase, various methods are employed to convert the solvent vector to solvate. Currently, my strategy involves vector concatenation, and subsequently transforming the combined vector into a novel encoding vector using Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP). The post-encoding phase involves channeling the vector through MLP, culminating in the generation of prediction values.

The evaluation of the models encompasses essential metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R-squared (R2) values. These metrics collectively offer a comprehensive assessment of the efficacy of different encoding methods and models. The experimental validation is conducted on the BigSolDB dataset curated by Lev Krasnov et al, comprising experimental solubility data under varying temperatures and with diverse solvents. This dataset provides a robust foundation for rigorously evaluating the predictive capabilities of the GNN-based models in real-world scenarios.

Literature, model, and descriptor review

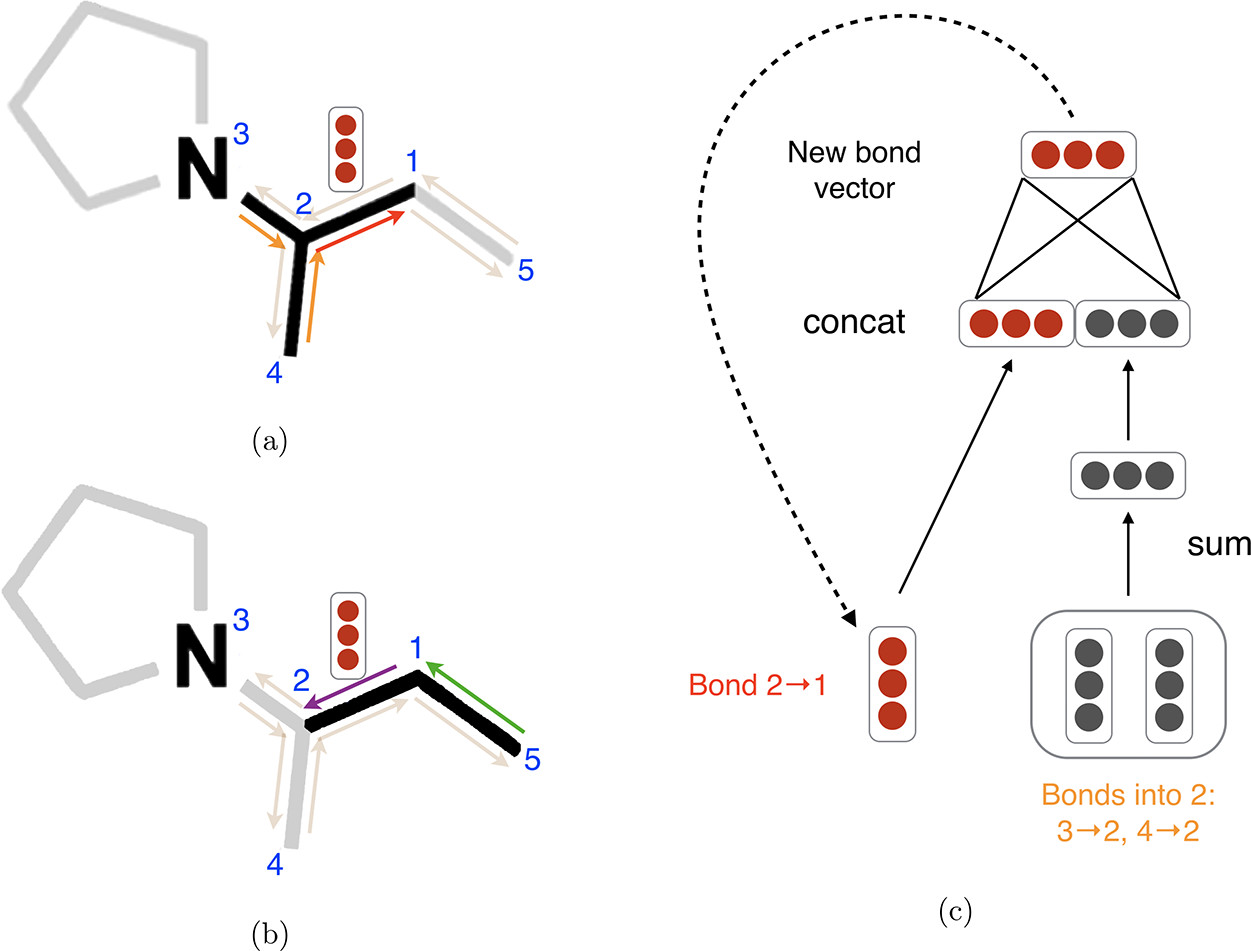

Graph Neural Network(GNN) based machine learning models are one of the most fastest growing and powerful modeling tools for molecular properties prediction that can be utilized in various applications, including material and drug design. One of the most powerful models that has been published is chemprop, a model developed by Kevin Yang et al. in 2019. In contrast to traditional GNN-based models which adopt MPNN, chemprop takes advantage of D-MPNN which delivers messages using direct edges. This approach can avoid unnecessary loops in the message-passing trajectory. The model also adopts an innovative message-passing strategy called belief propagation. The power of the model has been demonstrated on various tasks including absorption wavelength prediction(Kevin Greenman et al., 2022) and IR spectroscopy(Esther Heid et al., 2023).

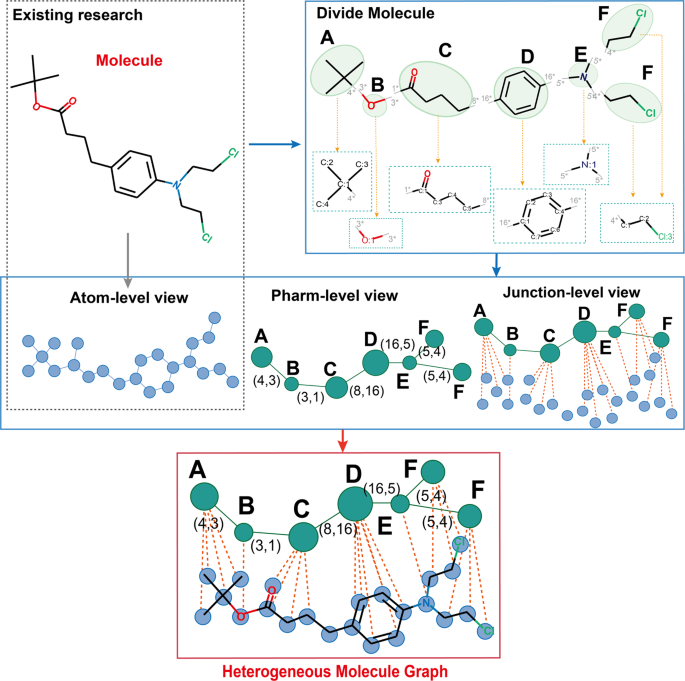

In tandem with chemprop, I integrate the Pharmacophoric-constrained Heterogeneous Graph Transformer (PharmHGT) into this project, a model crafted by Yinghui Jiang et al., tailored specifically for drug discovery. In addition to traditional nodes and edges representations corresponding to atoms and bonds in the molecules, the model creates supernodes based on the predefined pharmacophore groups(which are features that are necessary for molecular recognition) and connects those supernodes with the corresponding groups of atoms using junction edges. The model then employs message-passing neural networks on the heterogeneous graph, complemented by transformer layers serving as readout functions.

In implementing the descriptor approach, I incorporated three distinct types of descriptors: the Minnesota Solvation Database descriptors, compiled by Aleksandr V. Marenich et al. (referred to as mn descriptor), Solvent Polarity Descriptors gathered by Christian Richardt (referred to as Richardt descriptor), and Solvent Effect Descriptors collected by Javier Catalan (referred to as Catalan descriptor). These descriptors, each sourced from reputable studies and researchers, contribute diverse perspectives to the solubility analysis undertaken in this article.

Method

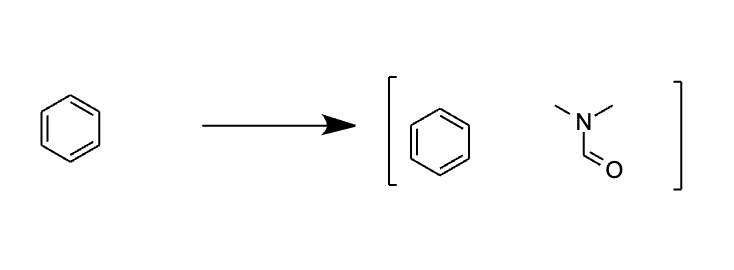

The BigSolDB dataset encompasses solubility data across various temperatures and solvents. To mitigate the temperature’s impact on solubility, I opted to focus on entries at the most prevalent temperature in the dataset—303.15 K—excluding all others. Subsequently, I transformed solubility values into logarithmic form, a commonly used measure in the realm of chemistry. I then test the PharmHGT model on the processed dataset by running two separate message-passing neural networks on both the solvent and the solvate molecules and concatenating the resulting feature vector to form a representation vector of the solvent-solvate system. Unexpectedly, the model encountered issues contrary to my initial expectations. The challenge lies in PharmHGT’s reliance on predefined pharmacophore groups to generate a graph representation of a given molecule. In instances where a molecule lacks pharmacophore groups—a commonplace scenario for small molecules like benzene or certain larger aromatic molecules—the model fails during initialization due to incorrect dimensions (specifically, 0 due to the lack of corresponding features). To overcome this hurdle, I devised the “graph augmentation approach.” For each solvent molecule, I introduced an auxiliary molecule (Dimethylformamide, DMF) containing predefined pharmacophore groups, facilitating the initialization steps. By merging the solvent graph with the auxiliary graph, the model can successfully run the initialization steps thanks to the presence of the extra junction edges in the graph.

To maintain parity with the chemprop model for fair comparisons, I refrained from augmenting solvate molecules with DMF. Instead, I excluded all molecules incompatible with the PharmHGT models. Post-filtering, the dataset was randomly partitioned into three segments: an 80% training set, a 10% testing set, and a 10% validation set. This preprocessing lays the groundwork for a rigorous evaluation of the models and ensures a comprehensive understanding of their performance in solubility prediction. I concatenates different kinds of solvent descriptors to the dataset and evaluate their performances separately.

Result

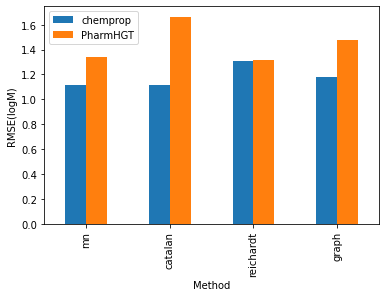

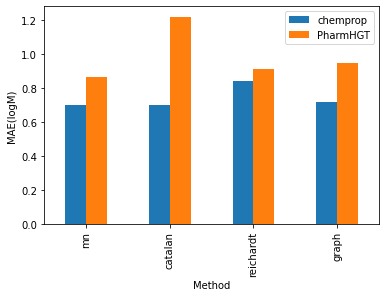

The processed data comprises 2189 entries in the training set, 273 entries in the testing set, and 267 entries in the validation set. I conducted training on the modified PharmHGT and chemprop models using this dataset. Both models exhibited promising results, showcasing a test RMSE ranging from 1 to 1.7, significantly influenced by the chosen encoding methods. Notably, chemprop consistently outperforms PharmHGT across all encoding methods, although the relative performance order varies. Within the chemprop model, the mn, catalan, and graph augmentations methods yield similar results, with a test RMSE ranging between 1.1 and 1.2 logM and a MAE ranging between 0.70 and 0.72 logM. Conversely, the reichardt descriptor performs less favorably, exhibiting a test RMSE of 1.31 logM and a test MAE of 0.84 logM . Intriguingly, in the PharmHGT model, these trends are reversed. The reichardt descriptor encoding attains the best performance with a test RMSE of 1.315846 and a second lowest test MAE of 0.91, while the catalan encoding method shows the highest test RMSE at 1.66 and the highest test MAE at 0.84. This discrepancy may be attributed to PharmHGT’s specialized design for drug molecules which typically have molecular weights ranging from 400 to 1000 Da. In contrast, solvent molecules generally possess molecular weights below 200 Da and often lack pharmacophore groups that provide additional information to the model. As a result, the model tends to be reduced to basic GNN models, focusing solely on modeling interactions between neighboring atoms and therefore ignoring the important functional groups that strongly influenced the solubility.

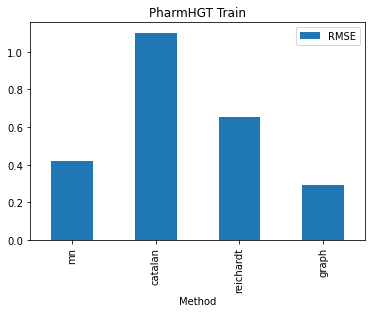

To validate this hypothesis, I conducted an analysis of the training RMSE across various encoding methods for PharmHGT. The finding reveals that the graph-augmentation methods beat all other methods by a huge margin. The graph augmentation method boasts a training RMSE of only 0.29 while all other methods exhibit training RMSEs of at least 0.42. This may also be attributed to the reduction of the PharmHGT models. The simple structures of solvent molecule graphs make the model susceptible to overfitting, resulting in a notably higher testing RMSE for the graph-augmentation method. Furthermore, my investigation uncovered that the catalan encoding method demonstrates a significantly higher training RMSE compared to other encoding methods, indicating that PharmHGT struggles to extract information from the descriptors. This aligns with the observation that the catalan encoding method also yields the largest testing RMSE among all encoding methods.

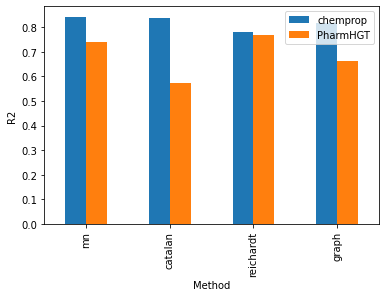

Examining the R2 scores reveals a consistent pattern, where the Chemprop model consistently beats the PharmHGT models across all employed encoding methods. Within the Chemprop model, the mn, catalan, and graph-augmentation methods exhibit similar outcomes, showcasing test R2 values ranging from 0.82 to 0.84. Conversely, the reichardt descriptor lags behind, presenting a less favorable test R2 of 0.78. These trends undergo a reversal within the PharmHGT model. The reichardt descriptor encoding achieves the best performance with a test R2 of 0.77, while the catalan encoding method records the lowest test R2 at 0.57. This intriguing reversal highlights the nuanced impact of encoding methods on model performance, emphasizing the need for tailored approaches based on the underlying molecular structures.

Conclusion

In the course of my experimentation, a consistent trend emerges wherein chemprop consistently outperforms pharmHGT across an array of encoding methodologies. Among these methodologies, the mn descriptor method maintains a stable, albeit moderate, level of performance, denoting its reliability without yielding any outstanding superiority.

A noteworthy observation manifests when employing the catalan descriptor method, which remarkably enhances the effectiveness of the PharmHGT model. Conversely, the chemprop model attains its peak performance when coupled with the reichardt descriptor methods and its worst performance when coupled with the catalan descriptor, showing that the strong dependencies of encoding methods across different models.

However, it is imperative to underscore that each encoding method exhibits inherent limitations, precluding the identification of a universally optimal solution applicable to both models concurrently. This nuanced understanding underscores the necessity for tailored approaches, grounded in an appreciation for the distinctive characteristics and demands of each model.

Further scrutiny into the training loss data reveals a notable constraint within the PharmHGT model. Its proclivity towards specificity for drug molecules renders it less adept at handling general tasks, necessitating the introduction of auxiliary graphs to augment its functionality. This intricacy adds a layer of consideration regarding the pragmatic applicability of the model in contexts beyond its primary pharmaceutical focus.

In navigating these findings, it becomes evident that the pursuit of a comprehensive and adaptable model mandates a nuanced comprehension of the interplay between encoding methodologies, model architecture, and the inherent limitations associated with specific domains.

Prospective works

Due to the complex nature of solvent-solvate interactions, a more rigorous splitting strategy that takes into account the distributions of different solvent molecules within the training, testing, and validation sets may be needed. Additionally, random splitting and cross-validation could be potential methods for improving the generality of the model. Finally, owing to the limited computational resources, this project only trained the model with default hyperparameters (such as batch size, layer width, number of tokens, etc.). Hyperparameter optimization can also be performed to gain a better understanding of the model’s capabilities.

Reference

-

Analyzing Learned Molecular Representations for Property Prediction https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00237

-

Pharmacophoric-constrained heterogeneous graph transformer model for molecular property prediction https://www.nature.com/articles/s42004-023-00857-x

-

Multi-fidelity prediction of molecular optical peaks with deep learning https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2022/sc/d1sc05677h

-

Minnesota Solvent Descriptor Database https://comp.chem.umn.edu/solvation/mnsddb.pdf

-

Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr00032a005

- Toward a Generalized Treatment of the Solvent Effect Based on Four Empirical Scales: Dipolarity (SdP, a New Scale), Polarizability (SP), Acidity(SA), and Basicity (SB) of the Medium https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jp8095727

- BigSolDB: Solubility Dataset of Compounds in Organic Solvents and Water in a Wide Range of Temperatures https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/6426c1d8db1a20696e4c947b

- Chemprop: A Machine Learning Package for Chemical Property Prediction https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/656f3bae5bc9fcb5c918caa2

data

The data and code for the experiments are available at https://github.com/RuiXiWangTW/solvent_encoding-data