Applications of Deep Learning in Timbre Transfer

Exploring musical timbre transfer by leveraging prior art in differential digital signal processing (DDSP) and modern deep learning structures.

Introduction

Timbre is what distinguishes a flute from a trumpet, piano or any other musical instrument. Even if two performers play the same note, there is no ambiguity in the tone of their instruments. But unlike pitch (frequency) or amplitude (loudness), timbre is not a trivial metric; rather, it pertains much more to subjective qualities like raspiness, articulation and even musical intent. In this article, I’ll be discussing different data-driven approaches to extracting and manipulating this quality of sound using deep learning.

In particular I’d like to explore timbre transfer, where one instrument is made to sound like another while retaining most aspects of the original performance. I’ll be training an auto-encoder architecture first conditioned on the source instrument (whistling) then tuned to tracks of trumpets to achieve whistling-to-trumpet timbre transfer. Moreover, I’d like to reduce the complexity of previous architectures to achieve realtime results suitable for musical performance.

First, some context on sound and our perception thereof.

What is Sound?

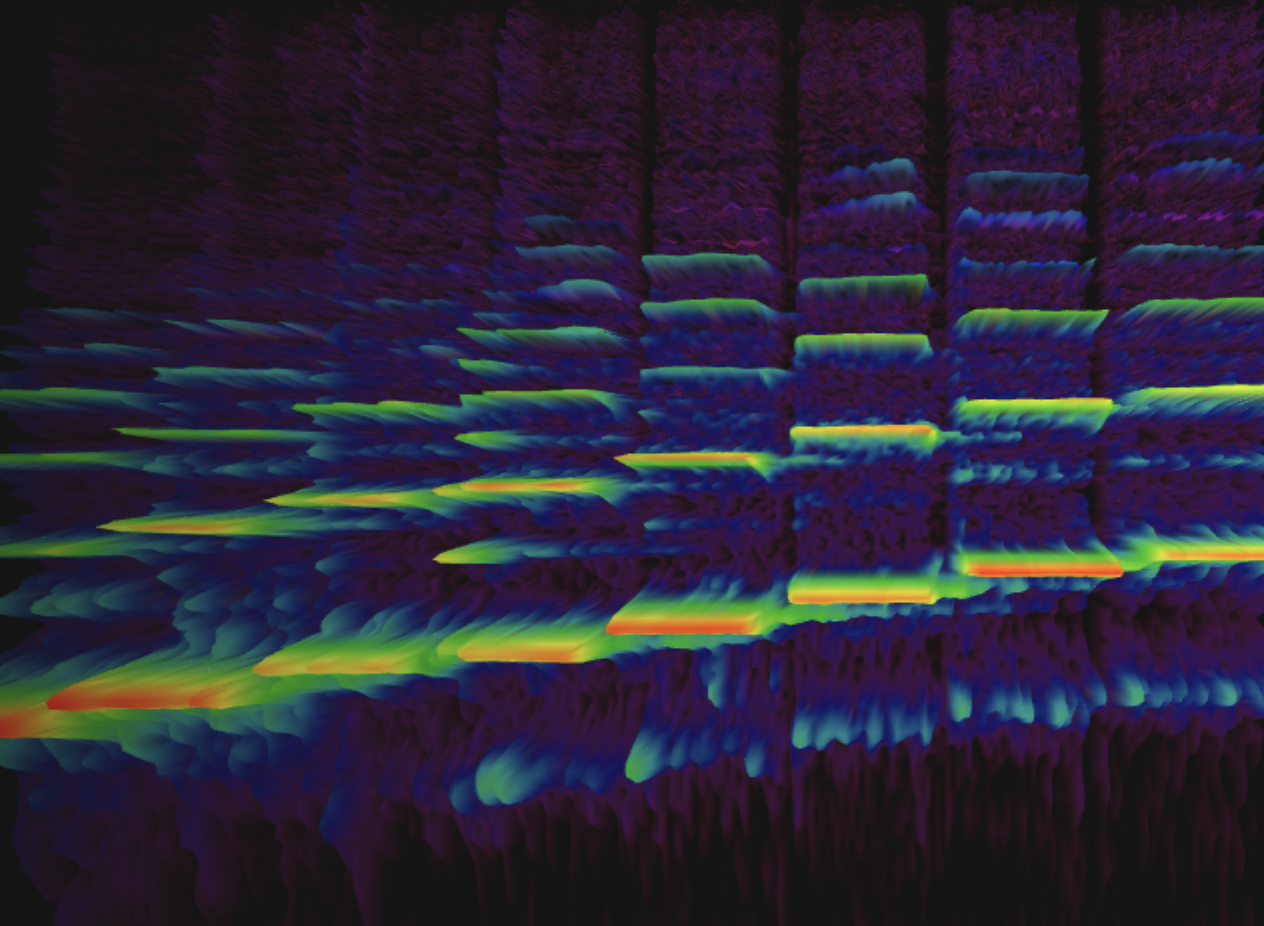

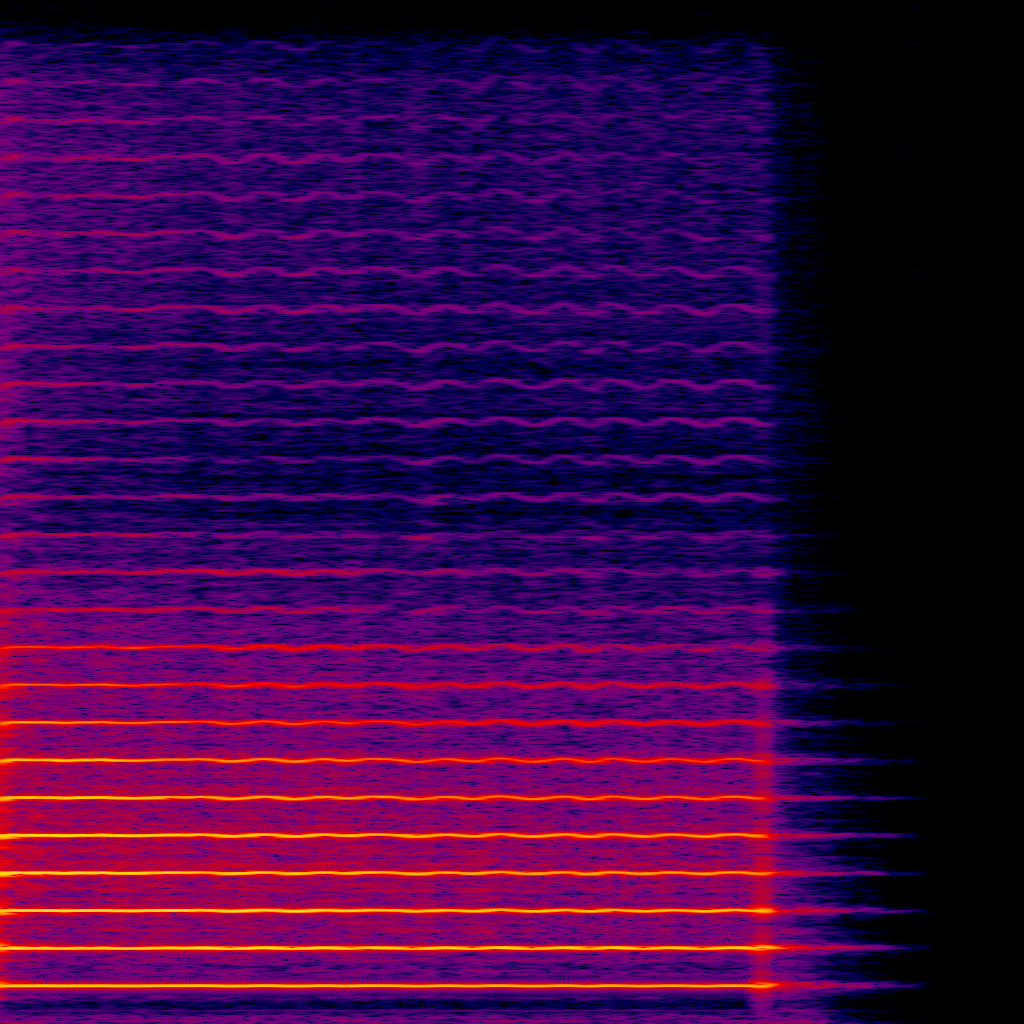

Our ears are sensitive to changes in air pressure over time, which we perceive as sound. Digital audio is analogous to this phenomenon, where its representation is a sequence of samples usually in the [-1, 1] range and discretized at a frequency high enough that it becomes indistinguishable from natural sources. This is known as the time domain, however all signals can be mapped to the frequency domain where the individual sinusoids that compose it are graphed against their respective amplitudes. Below is a Fourier transform

It turns out that only the bottom-most frequency, \(f_0\), informs our ears of this note’s pitch. In fact, a pure sine wave at that frequency will sound similar to the trumpet.

The distinction between the trumpet and sine wave lies in the frequencies above \(f_0\), known as overtones. Moreover, certain musical instruments exhibit an interesting harmonic behavior where only the overtones that are multiples of \(f_0\) are actually prominent; this is the case for most instruments you could name, though some non-examples include the gong and timpani

Try playing the audio clip above, whistle into the spectrogram or record your own instrument! The horizontal axis is time and vertical axis is frequency

So how do overtones relate to timbre? Well, the harmonic series is the most obvious distinguishing factor between different instruments playing the same pitch, so we could model timbre as the evolution of \(f_0\) and its overtones’ amplitudes over time. Note that this is assuming a strictly monophonic context (one note at a time), and overlooks non-harmonic parts of the signal (e.g. a flutist’s breathing). So this representation will still sound synthetic but it forms a good basis for what we’re trying to achieve.

Timbre Transfer

Perhaps the most obvious method for achieving timbre transfer is approximating the pitch of the source audio (as demonstrated above) and recreating it using a synthetic MIDI instrument. However, this discards much of the expressiveness which isn’t desireable in a musical performance.

Rather, data-driven approaches have shown promise in audio synthesis

| Keyboard | Guitar | String | Synth Lead |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Images courtesy of

However, these methods rely on a dataset of audio tracks in two timbre domains, namely audio synthesized from MIDI instruments like in

Proposed Model

I experimented with an auto-encoder architecture, where a network is trained to minimize the audible difference between some input audio track \(x\) and its re-synthesized counterpart \(\hat{x}\); so, the model attempts to recreate its input \(x\) by first encoding it to some latent representation \(z\) and decoding back to audio. Note that although over-fitting is possible, a one-to-one mapping (or, cheating) is impossible because \(z\) bottlenecks (has less dimensions than) \(x\). The appeal of this approach is that the problem is now self-supervised and can be trained directly on musical performances of the source instrument (e.g. whistling).

Next, the encoder is frozen (unaffected by gradient descent) and the decoder is trained anew on samples of the target instrument (e.g. trumpet). So, the networks knows how to encode the source instrument to some \(z\), and hopefully its decoder has adapted to map \(z\) onto the target instrument.

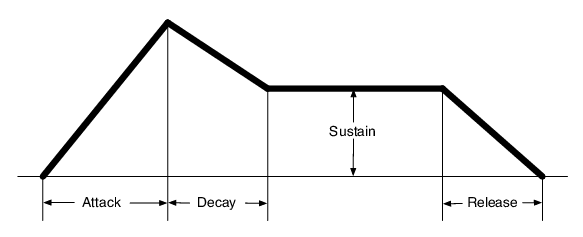

The decoder doesn’t output audio directly, nor does it generate a spectrogram like in

The encoder architecture is taken from

Finally, the loss I’m using is multi-scale spectrogram loss proposed in

Encoder

The architecture of my model is largely inspired by Magenta’s Differentiable Digital Signal Processing (DDSP)

In my experiment, I leverage a Convolutional Representation for Pitch Estimation (CREPE)

Decoder

introduced the idea of using oscillators for audio synthesis as opposed to raw waveform modeling.

Image courtesy of Tellef Kvifte

Dataset

I trained the target instrument auto-encoder on the URMP dataset

I also created my own whistling dataset, sampled from MIT students with varying levels of proficiency. The audio clips are normalized, silence is cutout and altogether I have around 2 hours of data.

Loss

Like

Results

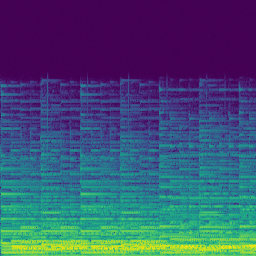

I trained 500 epochs of 16 times 4 second samples on a single M2 MacBook Air with Metal acceleration, totaling around 10 hours. Unfortunately, the loss converged but the network was not able to generalize over abstract characteristics of sound as I’d hoped. Rather, it learned to represent sound as a mellow mix of harmonics instead of anything useful. I think future experiments should penalize silence (or close to it), and perhaps add skip connections from the inputs’ power (explicitely calculated) to the decoder. Moreover, the size of the encoder was drastically reduced (a few orders of magnitude less parameters in both width and depth) so it’s possible the latent representation did not contain much meaningful data.

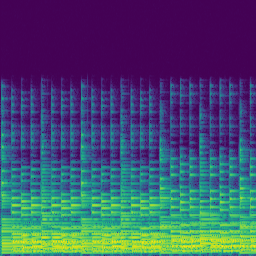

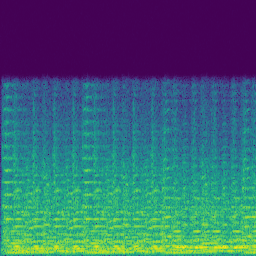

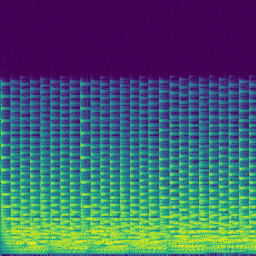

Sample synthesized waveforms at epochs 0, 250, and 470 respectively (loud sounds warning!).