Overparameterization of Neural Networks through Kernel Regression and Gaussian Processes

In this work, we will explore the successes of overparameterization of neural networks through evaluating the relationship between the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK), MLPs, and Gaussian processes.

Introduction

In this work, we will explore the successes of overparameterization of neural networks through evaluating the relationship between the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK), MLPs, and Gaussian processes. Recent work has shown that overparameterized neural networks can perfectly fit the training data yet generalize well enough to test data. This was formalized as “the double descent curve”

To help elucidite our understanding of neural networks as the width increases, I wanted to understand the connections between neural networks, which are often regarded as “black boxes,” and other classes of statistical methods, such as kernels and NNGPs. My goal is to put neural networks in the greater contexts of statistical machine learning methods that are hopefully easier to reason with and interpret.

Literature Review

There is already prior literature on the connections between these three classes of models.

-

Kernel Regression $\iff$ MLPs: This connection was introduced in

. In particular, they proved that the limit of a neural network as width approaches infinity is equivalent to kernel regression with the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK). -

MLP $\iff$ Gaussian Processes: The connection for infinitely-wide one-layer neural networks was introduced in

and for deep networks in . This comes from the observation that if the weights are sampled Gaussian i.i.d., then the Central Limit Theorem states that as the width approaches infinity, the output is also Gaussian. We also went over this briefly in class. -

Gaussian Processes $\iff$ Kernel Regression: Other than the obvious fact that they both use kernels and the “kernel trick,” I could not really find a resource that established a clear connection between the two other than through the intermediary of MLPs. In this project, this is one link that I will try to explicitly establish.

Other relevant prior works I reviewed include:

- The formalization of the double descent curve in

, which uprooted our previous understanding of the bias-variance tradeoff and the notion that models should not overfit. This also motivates the use of infinite-wide neural networks (extreme overparameterization) for prediction tasks. Otherwise, conventional wisdom would say that these models overfit. - Why is this problem even interesting? This paper

shows that kernels achieve competitive performance for important matrix completion tasks, so neural networks are not necessarily the only solution to many tasks of interest. - The lecture notes from this IAP class. I used some of the notation, definitions, and theorems from the lecture notes to write this post, but I also worked through some of the math on my own (e.g. the overparameterized linear regression proof for general $\eta$ and $w^{(0)}$, proving that $X^\dagger$ minimizes $\ell_2$ norm, etc.).

- I also used this blog to better understand the intuition behind NTKs.

The gaps in prior knowledge I want to tackle include (1) the explicit connection between GPs and kernel regression and (2) how sparsity of kernel regression can help explain the generalization abilities of neural networks.

My Contributions

- The explicit connections between kernel regression, MLPs, and Gaussian Processes (GP), particularly kernel regression and GP.

- How properties of overparameterized linear/kernel regression can help us understand overparameterization of neural networks, particularly the regularization of the weights.

- Empirical demonstrations of the theory developed here.

To start, I work through the math to understand overparameterization in linear regression and connect the results to overparameterization in kernel regression.

Overparameterization in Linear Regression

Linear regression involves learning a predictor of the form $\hat{f}(x) = wx$, where $w \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times d}, x \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times 1}$. Much like neural networks, we find $\hat{w}$ by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of the prediction $\hat{f}$ from the target $y \in \mathbb{R}$ across all $n$ samples: \(\mathcal{L}(w) = \frac{1}{2}||y - \hat{f}(x)||_2^2\)

Without knowing much about the relationship between $n$ and $d$, it is not obvious that there is a closed form solution to this system of equations. Of course, if $n = d$ (and $X$ is full rank), then we can directly solve for $w$. Specifically, if $Y \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times n}$, $X \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times n}$, $w \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times d}$, then \(Y = wX \implies w = YX^{-1}.\)

What about when $n < d$ (underparameterized regime) or $n > d$ (overparameterized regime)? We need to turn to gradient descent then, \(w^{(t+1)} = w^{(t)} - \eta \nabla_w \mathcal{L}w^{(t)}.\) We can actually explicitly characterize the conditions for convergence and its limit for different values of the learning rate $\eta$ and initialization $w^{(0)}$. Namely, let us start with \(w^{(t+1)} = w^{(t)} - \eta \nabla_w \mathcal{L}(w^{(t)}) = w^{(t+1)} = w^{(t)} - \eta (-(y - w^{(t)}X))X^\top = w^{(t)} + \eta (y - w^{(t)}X)X^\top\) Using this equation, we can derive a closed form expression for $w^{(t)}$. \(\begin{align*} w^{(t+1)} &= w^{(t)} + \eta (y - w^{(t)}X)X^\top = w^{(t)} +\eta yX^\top - \eta w^{(t)} XX^\top = w^{(t)}(I - \eta X X^\top) + \eta y X^\top \\ w^{(1)} &= w^{(0)} (I - \eta XX^\top) + n y X^\top\\ w^{(2)} &= w^{(0)} (I - \eta XX^\top)^2 + n y X^\top(I - \eta XX^\top) + n y X^\top\\ w^{(3)} &= w^{(0)} (I - \eta XX^\top)^3 + n y X^\top(I - \eta XX^\top)^2 + n y X^\top(I - \eta XX^\top) + n y X^\top\\ &\dots\\ \end{align*}\) Let $A = (I - \eta XX^\top)$, $B = nyX^\top$, and $X = U\Sigma V^\top$ be the singular value decomposition of $X$ where $\sigma_1 \geq \dots \geq \sigma_r$ are the non-zero singular values. Then \(\begin{align*} w^{(t)} &= w^{(0)}A^\top + BA^{t-1} + BA^{t-2} + \dots + BA + B = w^{(0)}A^\top + B(A^{t-1} + A^{t-2} + \dots + A + I) = w^{(0)} A^t + (nyX^\top)(UU^\top + U(I - n\Sigma^2)U^\top + \dots + U(I - n\Sigma^2)^{t-1}U^\top) \\ &= w^{(0)} A^t + (nyX^\top)U(I + (I - n\Sigma^2) + \dots + (I - n\Sigma^2)^{t-1})U^\top = w^{(0)}(I - n XX^\top)^t + nyX^\top U\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1 - (1 - \eta\sigma_1^2)^t}{n\sigma_1^2} & & &\\ & \frac{1 - (1 - \eta\sigma_2^2)^t}{n\sigma_2^2} & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}U^\top \end{align*}\\\) From this equation, we can derive many insights into the conditions for convergence. In particular, if we want the RHS to converge, we require $|1 - \eta \sigma_1^2| < 1 \implies -1 < 1 - \eta\sigma_1^2 < 1$. Thus, when $\eta < \frac{2}{\sigma_1^2}$ (which implies $\eta \leq \frac{2}{\sigma_2^2}, \eta \leq \frac{3}{\sigma_3^2}, \dots$), gradient descent for linear regression converges.

With this condition on $\eta$, we can further characterize $w^{(\infty)}$. \(\begin{align*} w^{(\infty)} &= \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} w^{(0)}(I - \eta XX^\top)^t + n yX^\top U \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{n\sigma_1^2} & & &\\ & \frac{1}{n\sigma_2^2} & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}U^\top = \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} w^{(0)}(UU^\top - \eta U \Sigma^2 U^\top)^t + yV\Sigma^\top U^\top U \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_1^2} & & &\\ & \frac{1}{\sigma_2^2} & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}U^\top \\ &= \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} w^{(0)}U(I - \eta \Sigma^2)^tU^\top + yV\Sigma^\top \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_1^2} & & &\\ & \frac{1}{\sigma_2^2} & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}U^\top = w^{(0)}U\begin{bmatrix} 0 & & &\\ & 1 & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 1 \end{bmatrix}U^\top + yV\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_1} & & &\\ & \frac{1}{\sigma_2} & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}U^\top =w^{(0)}U\begin{bmatrix} 0 & & &\\ & 1 & &\\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & 1 \end{bmatrix}U^\top + yX^\dagger \\ \end{align*}\) Note the dependency on this result on $w^{(0)}$. If $w^{(0)} = 0$, then $w^{(\infty)} = yX^\dagger$. Furthermore, we can also prove that $w = yX^\dagger$ is the minimum $\ell_2$ solution. Suppose there exists another solution, $\tilde{w}$. If $Xw = X\tilde{w}$, then $\tilde{w} - w \perp w$ because \((\tilde{w} - w)w^\top = (\tilde{w} - w)w^\top = (\tilde{w} - w)(y(X^\top X)^{-1}X^\top)^\top = (\tilde{w}-w)X(X^\top X^{-1})^\top y^\top = 0\) Thus, \(\|\tilde{w}\|_2^2 = \|\tilde{w} - w + w\|_2^2 = \|\tilde{w} - w\|_2^2 + \|w\|_2^2 + 2(\tilde{w}-w)w^\top = \|\tilde{w} - w\|_2^2 + \|w\|_2^2 \geq \|w\|_2^2.\)

This characterization is consistent when $n = d$, $n < d$, and $n > d$. If $n = d$, then $X^\dagger = (X^\top X)^{-1} X^\top = X^{-1}(X^{\top})^{-1} X^\top = X^{-1}$. When $n > d$ and the rank of $X$ is $d$, then when $\nabla_w \mathcal{L}(w) = 0$, then $(y-wX)X^\top = 0 \implies w = yX^\top(XX^\top)^{-1}$. $XX^\top \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}$ is invertible since $X$ is full rank, so $w = yX^\top(XX^\top)^{-1} =y(X^\top X)^{-1}X^\top = yX^\dagger$.

We are particularly interested in the overparameterized regime, i.e. when $n > d$. The results above show that when $w^{(0)} = 0$, even though there are an infinite number of $w$ that satisfy $y = Xw$, gradient descent converges to the minimum $\ell_2$-norm solution, $w = yX^\dagger$. This sparsity may help prevent overparameterization even when there are enough parameters to fully memorize the input data.

Why is this analysis helpful? This characterization may help us understand the solution obtained by kernel regression, which can be viewed as just linear regression on a nonlinear, high-dimensional space.

Overparameterization in Kernel Regression

We will start with a brief definition of kernel regression. Intuitively, kernel regression is running linear regression after applying a non-linear feature map, $\psi$, onto the datapoints $x \in \mathbb{R}^{d}$. Formally, we require that $\psi: \mathbb{R}^{d} \rightarrow \mathcal{H}$, $w \in \mathcal{H}$, and the predictor $\hat{f}: \mathbb{R}^{d} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ to take the form $\langle w, \psi(x)\rangle_{\mathcal{H}}$, where $\mathcal{H}$ is a Hilbert space. A Hilbert space is a complete metric space with an inner product. Intuitively, Hilbert spaces generalize finite-dimensional vector spaces to infinite-dimensional spaces, which is helpful for us because this allows for infinite-dimensional feature maps, an extreme example of overparameterization. All the finite-dimensional inner product spaces that are familiar to us, e.g. $\mathbb{R}^n$ with the usual dot product, are Hilbert spaces.

At first glance, it might seem impossible to even store the weights of infinite-dimensional feature maps. However, this problem is resolved by the observation that weights from solving linear regression will always a linear combination of the training samples. In particular, since $yX^\dagger$ has the same span as $X$, we can always rewrite the weights as $w = \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i x_i^\top$, where $x_i$ denotes the $i$ th sample. What’s really interesting is that this can be extended to kernels as well.

Specifically, for kernel regression, we seek a solution to the MSE problem: \(\mathcal{L}(w) = \|y-\hat{x}\|_2^2 = \|y-\langle w,\psi(x)\rangle\|_2^2.\)

We know that the weights must take the following form, \(w = \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i \psi(x_i).\)

Thus, expanding out the loss function, we have that \(\mathcal{L}(w) = \frac{1}{2}\|y-\langle w, \psi(x)\rangle\|_2^2 = \frac{1}{2}\|y-\langle \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i \psi(x_i), \psi(x_i)\rangle\|_2^2 = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^n (y_j -\langle \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i \psi(x_i), \psi(x_j)\rangle)^2 = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^n (y_j -\langle \alpha, \begin{bmatrix} \langle \psi(x_1), \psi(x_j) \rangle \\ \langle \psi(x_2), \psi(x_j) \rangle \\ \vdots \\ \langle \psi(x_n), \psi(x_j) \rangle \\ \end{bmatrix}\rangle)^2.\)

Thus, rather than storing the weights $w$ that act on the feature map directly, we just need to store $\alpha$, the weights acting on the samples. Moreover, another observation from this equation is that we don’t even need to define the feature map directly. We only need to store the inner product of each sample with every other sample. Formally, this inner product is called a kernel ($K: \mathbb{R}^d \times \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$). With a slight abuse of notation, we will also use $K$ to denote the matrix of inner products, $K(X,X)$.

Much like our discussion in class on Gaussian Processes (GP), kernels can be thought of as a “distance” or “covariance” function on samples. Some well-known kernels include:

- Gaussian kernel: $K(x,\tilde{x}) = \exp(|x - \tilde{x}|_2^2)$

- Laplacian kernel: $K(x,\tilde{x}) = \exp(|x - \tilde{x}|_2)$

- Neural Tangent kernel with ReLU activation: $K(x,\tilde{x}) = \frac{1}{\pi}(x^\top \tilde{x}(\pi - \arccos(x^\top \tilde{x})) + \sqrt{1 - (x^\top \tilde{x})^2}) + x^\top \tilde{x}\frac{1}{\pi}(\pi - \arccos(x^\top \tilde{x}))$

- Linear kernel: $K(x,\tilde{x}) = x^\top \tilde{x}$

The linear kernel is equivalent to linear regression, and (as we will explore later), the Neural Tangent kernel with ReLU activation approximates an infinitely wide neural network with $\phi(z) = \sqrt{2}\max(0,z)$ activation.

Note also that all of these kernels, however finite, represent infinite-dimensional feature maps. For example, the feature map for the Gaussian kernel is $\psi(x) = \Big(\sqrt{\frac{(2L)^m}{p_1!p_2!\dots p_d!}}x_1^{p_1}x_2^{p_2}\dots x_d^{p_d}\Big)_{p_1,p_2,\dots,p_d \in \mathbb{N} \cup {0}}.$ It is remarkable that kernel regression even does well in practice considering it works in an extremely over-parameterized regime.

However, our analysis using linear regression may shed some light on why. In particular, recall that our loss function is \(\mathcal{L}(w) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^n (y_j - \alpha K(X,X)).\)

Since this is just linear regression in $\mathcal{H}$, gradient descent converges to $\alpha = yK^\dagger$ if $\alpha^{(0)} = 0$. This means the predictor for kernel regression looks like \(\hat{f}(x) = \alpha K(X,x) = yK^{\dagger}K(X,x).\)

Since $K(X,X)$ is a square matrix, (technically, $n = d$ from the linear regression case), this equation can be solved directly. Moreover, $\alpha$ is the minimum $\mathcal{H}$-norm solution, just like how the weights from the linear regression model is the minimum $\ell_2$-norm solution.

The ability to be solved in closed form is an important property of kernel regression. In practice, $\alpha^{(0)}$ cannot be initialized to $0$ in gradient descent, so neural networks do not necessarily converge to the minimum-norm solution that kernels do. This may offer some explanation for the predictive ability of kernels on tabular data.

Now, let us formally define the Neural Tangent Kernel. The NTK for a neural network is defined as the outer product of the gradients of the network’s output with respect to its parameters, averaged over the parameter initialization distribution. Formally, if $f(x; w)$ is the output of the network for input $ x $ and parameters $ w $, the NTK is given by:

\[K_{\text{NTK}}(x, \tilde{x}) = \mathbb{E}_{w}\left[\left\langle \frac{\partial f(x; w)}{\partial w}, \frac{\partial f(\tilde{x}; w)}{\partial w} \right\rangle\right].\]The intuition for this comes from understanding how parameters change in neural networks during gradient descent.

In particular, note that \(\frac{df(x;w)}{dt} = \frac{df(x;w)}{dw} \frac{dw}{dt} \approx \frac{df(x;w)}{dw} (-\nabla_w \mathcal{L}(w)) = -\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N \underbrace{\nabla_w f(x;w)^\top \nabla_w f(x_i;w)}_{NTK} \nabla_f\mathcal{L}(f,y_i).\)

From this equation, we see that during gradient descent, the network $f$ changes based on its effect on the loss function weighted by the “covariance”/”distance” of $x$ w.r.t. the other samples. The intuition for the NTK thus comes from the way that the neural network evolves during gradient descent.

established that training an infinite-width neural network $f(x;w)$ with gradient descent and MSE loss is equivalent to kernel regression where the kernel is the NTK.

To further understand the connections between the NTK and wide neural networks, I benchmarked the performance of wide neural networks and the NTK on the task of predicting the effects of a gene knockout on a cell.

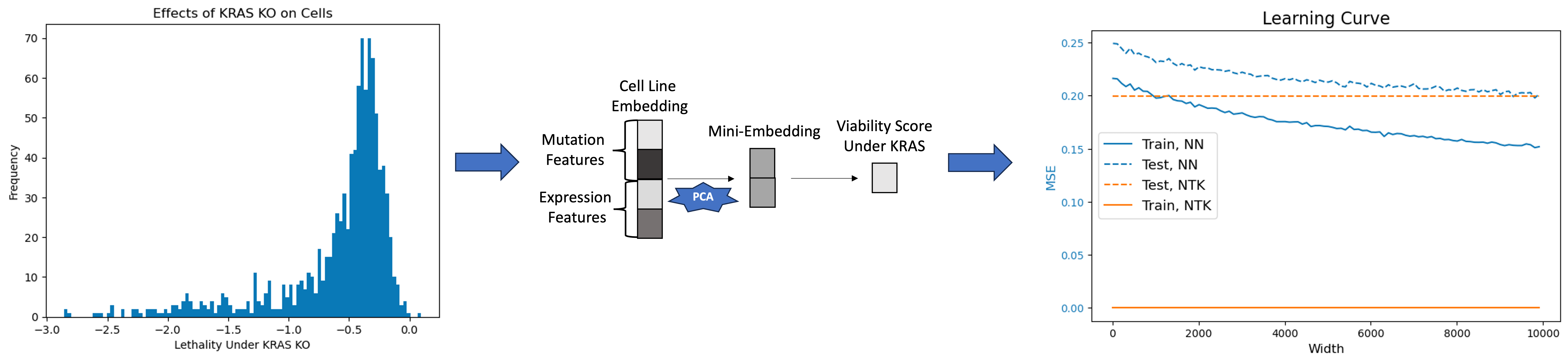

Figure 1. Experiment workflow.

All the datasets are publicly available on DepMap and I processed the data the same way as I did in

Biological datasets are well-suited for the analysis of overparameterized models because the embeddings are by default extremely high-dimensional, i.e. $d » n$. However, since I want to test the effects of increasing the width of neural networks and I do not want the shape of the weight matrix to be $\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}\mathbb{R}^{30,000 \times k}$, I reduced the computational complexity of this problem by first running PCA on the cell embedding to reduce $d$ to $500$. Thus, $X \in \mathbb{R}^{998 \times 500}$ and $Y \in \mathbb{R}^{998 \times 1}$. I did a simple 80/20 training/test split on the data, so $X_{train} \in \mathbb{R}^{798 \times 500}$ and $X_{test} \in \mathbb{R}^{200 \times 500}$.

I then benchmarked a one hidden layer MLP, i.e. $A\phi(Bx)$ with ReLU activation, where $A \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times 1}, B \in \mathbb{R}^{500 \times k}$, as $k$ ranged from ${10,110,210,\dots,9,910}$. I also benchmarked the NTK on the same task. There are several interesting insights from this experiment.

- The NTK always exactly fits the training data by construction because we directly solve the MSE problem.

- The MSE of a neural network as $k$ increases approaches the MSE of the NTK, which aligns with the theory. However, I want to note that if I shrink $d$, i.e. if I take $d = 10$ or $d=100$, the second point does not always hold. In those cases, the MSE of the NTK is much larger than the MSE of the neural network. That was a bit counterintuitive, but one explanation could be that the NTK is a poor approximation for the neural network in those cases because the neural network cannot be linearized when it is changing so drastically based on the small set of features.

- The MSE asymptotically decreases as $k \rightarrow \infty$. This aligns with the theory of the double-descent curve. It would be interesting to test if the weights learned by the MLP enforces some sort of sparsity, e.g. by plotting $\frac{|A|_2}{|x|_2}$, where $A,x \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times 1}$ and $x \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I_k)$ (unfortunately, the latter does not have a nice form).

Gaussian Processes

Compared to linear and kernel regression, a Gaussian Process (GP) is a much more general class of nonparametric functions. Formally, a Gaussian Process (GP) is a collection of random variables, any finite number of which have a joint Gaussian distribution. A GP can be thought of as a distribution over functions and is fully specified by its mean function $\mu(x)$ and covariance function $K(x, \tilde{x})$, (similar to kernel regression, this is also known as the kernel of the GP).

Given a set of points $X = {x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n}$, the function values at these points under a GP are distributed as:

\[\mathbf{f}(X) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{\mu}(X), K(X, X)),\]where $ \mathbf{\mu}(X) $ is the mean vector and $ K(X, X) $ is the covariance matrix constructed using the kernel function $K$.

Key to the concept of Gaussian Processes is the closure of multivariate Gaussians under conditioning and marginalization. Since all the function values are jointly Gaussian, the value of a new function value, given the existing ones, is also Gaussian, e.g. assuming $\mu(X) = 0$,

\(f(x_{test}) | f(x_1)\dots f(x_n) = \mathcal{N}(\mu_{test},\Sigma_{test})\) where $\mu_{test}$ = $K(x,X)K(X,X)^{-1}f(X)$ and $\Sigma_{test}$ = $K(x,x) - K(x,X)K(X,X)^{-1}K(x,X)$. (The math for this is a bit tedious, so I omit that here.)

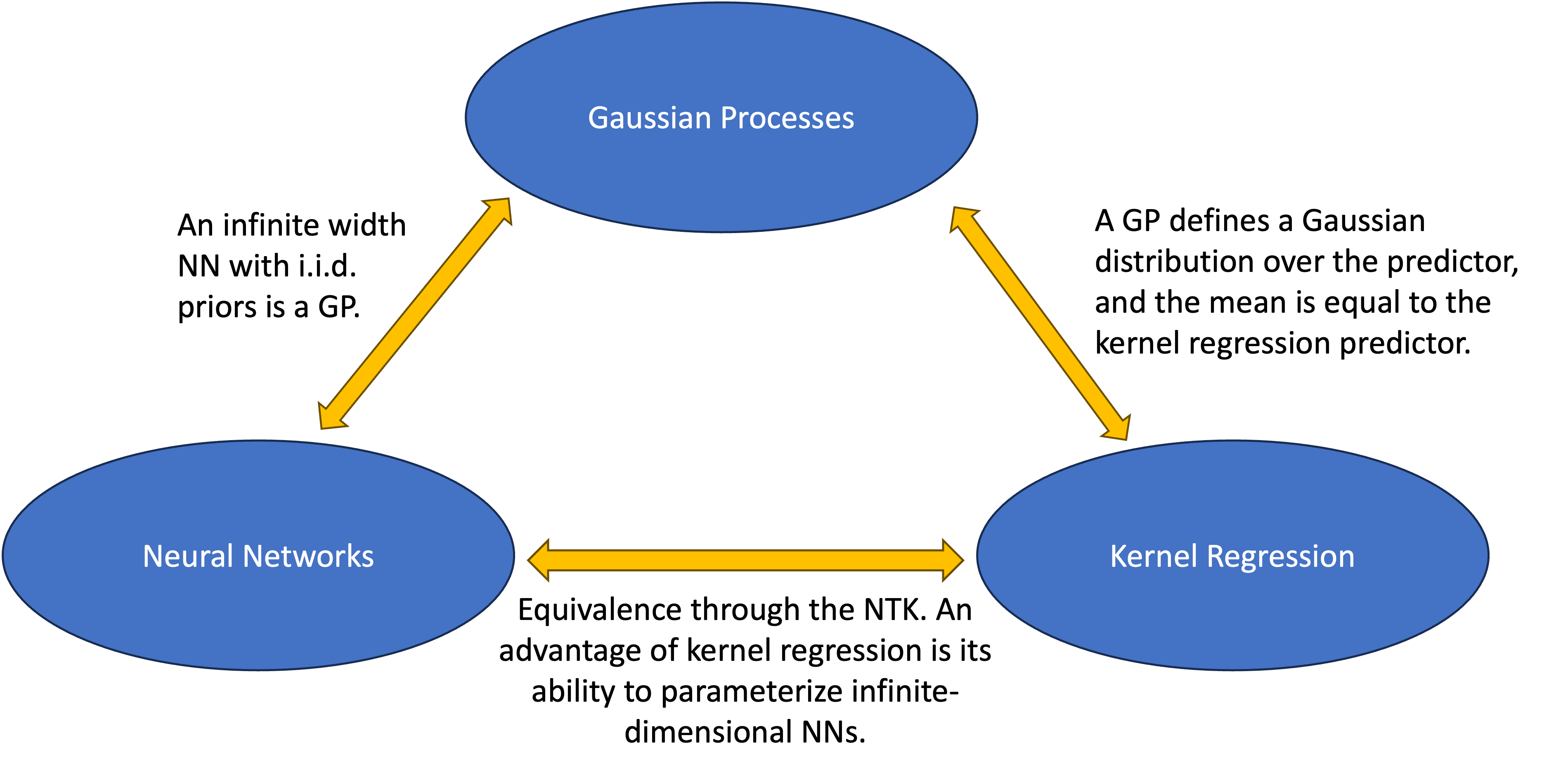

Connecting Gaussian Processes, Kernel Regression, and MLPs

It is interesting to note the similarities between this closed form for the predictor of a Gaussian process and the predictor for kernel regression. In fact, $\mu_{test}$ is exactly the same as $\hat{f}(x){kernel}$. This suggests GPs parameterize the class of functions drawn from a normal distribution with mean $\mu{test}$ while kernel regression converges to a deterministic function that is exactly $\mu_{test}$. In other words, I think that the function learned by kernel regression can be thought of as the maximum of the posterior distribution of the GP with the same kernel.

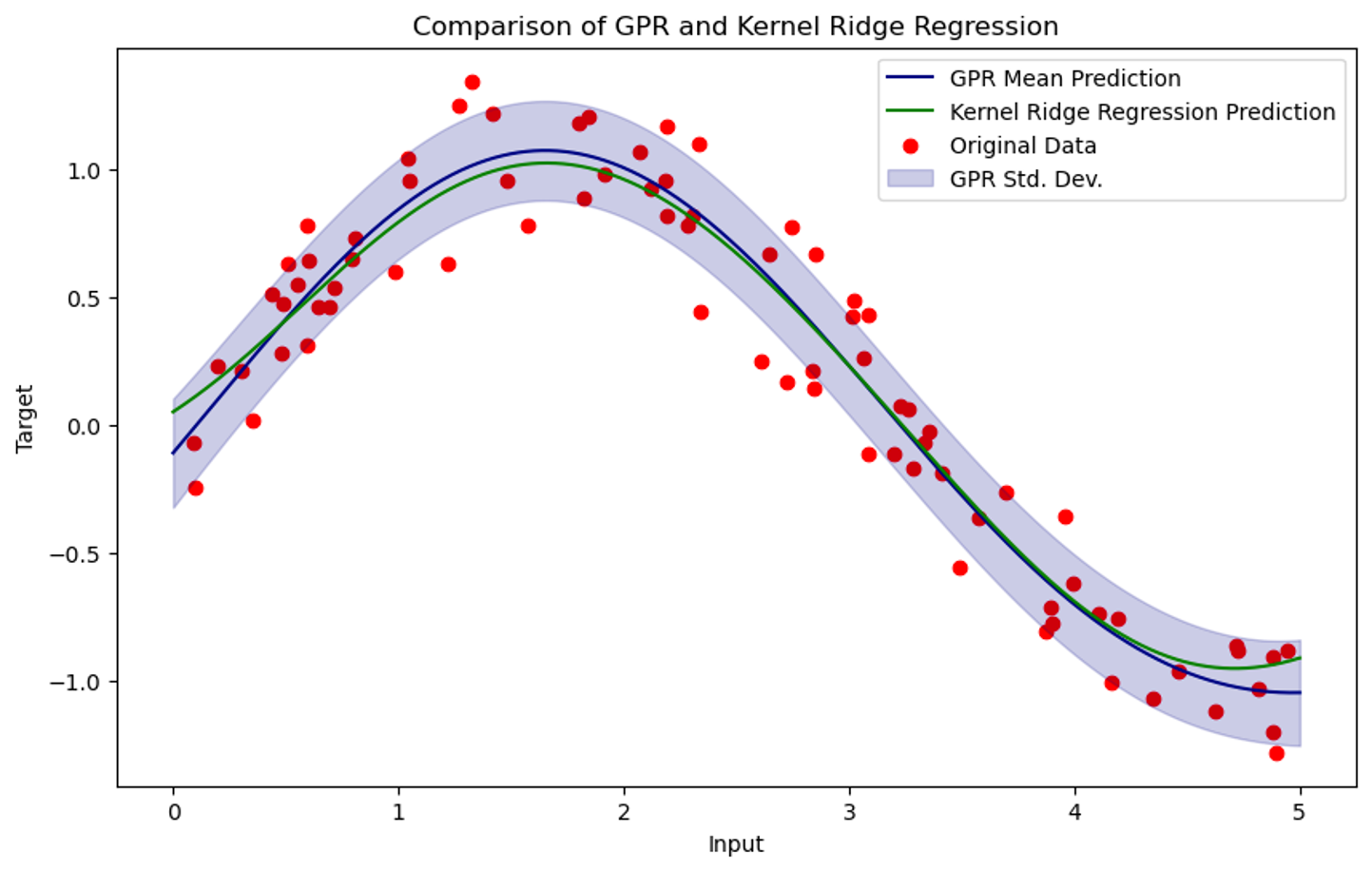

To test this insight, I ran an experiment to see how similar a Gaussian Process trained on a fixed dataset is to kernel regression with the same kernel.

Figure 2. Results of Gaussian Process Regression and Kernel Ridge Regression on synthetic data with the same kernel function.

I sampled $X \sim \mathcal{N}(5,1)$ and $Y \sim \sin(X) + \mathcal{N}(0,0.2)$. I then trained a Gaussian Process and kernel ridge regression on the data with $K(x,\tilde{x}) = -\exp{\frac{|x-\tilde{x}|_2^2}{2}} + Id$. As expected, the function learned by kernel ridge regression closely matches the mean of the class of functions learned by the GP.

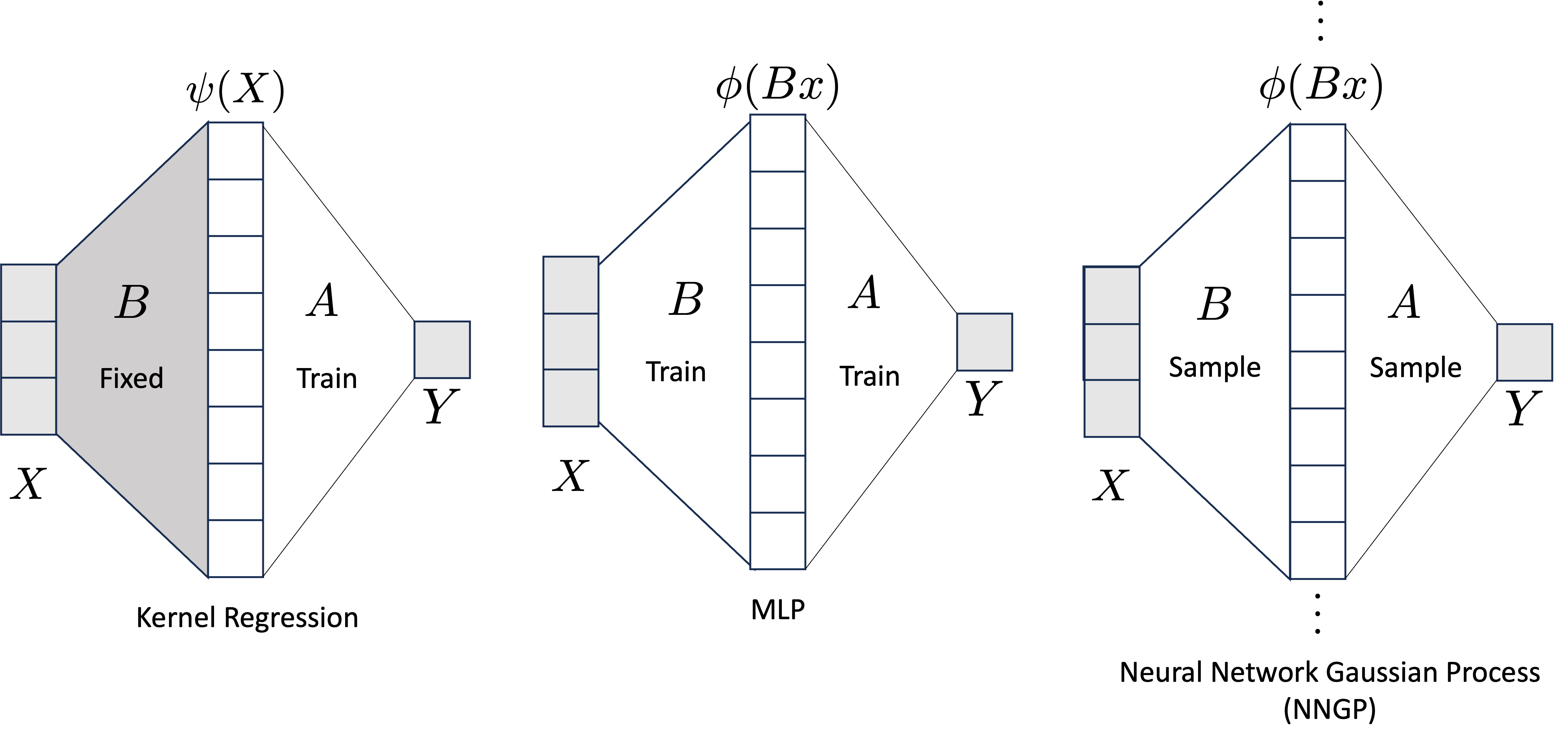

Another connection between kernel regression and GPs can be made through the introduction of a one hidden layer MLP. See below figure.

Figure 3. Visualization of kernel regression, MLPs, and Gaussian Processes.

Starting with kernel regression, if we fix the “feature map,” $B $, then training gradient descent with $A^{(0)} = 0$ is equivalent to training kernel regression with $K(x,\tilde{x}) = \langle \phi(Bx), \phi(Bx) \rangle$. This is intuitive because again, we can just think of kernel regression as linear regression ($A$) after applying a nonlinear feature map, ($\phi \circ B$).

The connection between neural networks and Gaussian Processes is a bit more complicated. Suppose we are in the overparameterized regime and $A \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times k}$ and $B \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times d}$. Forgoing the bias term out of simplity, the output of the network is \(f(x) = A\phi(Bx) = \sum_{i=1}^k A_i\phi(Bx)_i.\) If the weights of the network are sampled i.i.d. Gaussian, then $f(x)$ is a sum of i.i.d. Gaussians and so as $k \rightarrow \infty$, the Central Limit Theorem states that the output of the network will also be Gaussian with some fixed mean and covariance, i.e. in the limit, \(f(x) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\Sigma)\) \(\begin{bmatrix} f(x_1) \\ f(x_2) \\ \vdots \\ f(x_n) \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,K)\)

Now, let us compute $K$: \(K(x,\tilde{x}) = \mathbb{E}[f(x)f(\tilde{x})] = \mathbb{E}[A\phi(Bx)A\phi(B\tilde{x})] = \mathbb{E}\Big[\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}\Big(\sum_{i=1}^k A_i \phi(Bx)_i\Big)\Big(\sum_{i=1}^k A_i \phi(B\tilde{x})_i\Big)\Big]\) Suppose for simplicity that $A \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I)$. Then $\mathbb{E}[A_iA_j] = 0$ and $\mathbb{E}[A_iA_i] = 1$: \(= \mathbb{E}\Big[\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty}\sum_{i=1}^k A_i^2 \phi(Bx)_i\phi(B\tilde{x})_i\Big] = 1 \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{i=1}^k \phi(Bx)_i\phi(B\tilde{x})_i= \underbrace{\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \langle \phi(Bx),\phi(B\tilde{x}) \rangle}_{k \times NNGP}.\)

The latter is essentially the definition of the Neural Network Gaussian Process, which is the kernel of the Gaussian Process that neural networks converge to when its width goes to infinity. (The NNGP has an extra $\frac{1}{k}$ term to allow the Law of Large Numbers to be used again.)

Ultimately, what this shows is that a neural network of infinite width over i.i.d. parameters is the class of Gaussian functions parameterized by the Neural Network Gaussian Process. With gradient descent, neural networks and kernel regression converge to a deterministic function that can be thought of as a sample from a GP.

The below figure summarizes my findings on the connections between the three types of function classes:

Figure 4. Comparison of kernel regression, MLPs, and Gaussian Processes.

Discussion

To summarize, these are the implications of the NN-Kernel Regression-GP Connection:

- Predictive Distribution: In the infinite-width limit, the predictive distribution of a neural network for a new input $x_{test}$ can be described by a Gaussian distribution with mean and variance determined by the NNGP.

- Regularization and Generalization: Kernels inherently regularize the function space explored by the network. This regularization is not in the form of an explicit penalty but may arise from the minimum $\mathcal{H}$-norm solution of kernel regression. This may explain the observed generalization capabilities of wide neural networks.

- Analytical Insights: This correspondence provides a powerful analytical tool to study the learning dynamics of neural networks, which are often difficult to analyze due to their non-linear and high-dimensional nature.

Limitations

A major limitation of this current work is that I evaluated overparameterized neural networks only through the lens of kernels/GPs. It would be interesting to try to understand the successes of neural networks through other metrics, such as evaluating test risk as width increases. Furthemore, it would also be interesting to characterize what happens when depth, rather than just width, increases. Another interesting next step would be expanding this analysis to understanding overparameterization of other architectures, such as CNNs and transformers, and their connections to kernel regression and Gaussian Processes.

Understanding neural networks through the lens of the NTK and Gaussian processes deepens our appreciation of the foundational principles in machine learning. It unifies three seemingly disparate areas: the powerful yet often opaque world of deep learning, the straightforward approach of kernel regression, and the rigorous, probabilistic framework of Gaussian processes. This confluence not only enriches our theoretical understanding but also paves the way for novel methodologies and insights in the practical application of machine learning algorithms.