Multimodal Commonsense

6.S898 project for analyzing and evaluating the commonsense reasoning performance of multimodal vs text-only models.

Introduction

In recent years, language models have been proven to be quite proficient in producing human-like text, computing somewhat semantically-meaningful and human-interpretable word and token embeddings, and generating realistic conversation. However, there is a vast distinction between mimicking human linguistics from data and forming an understanding of the world and its abstract connections from data. The latter describes the commonsense knowledge of a language model, or its ability to reason about simple relationships, interactions, and general logic of the world.

With the advent and growth of large language models in recent years (and months), understanding the world and developing deeper underlying representations of physical and abstract concepts through text alone has become much more feasible and tractable. Yet, there is only so much someone or something can understand by simply reading about it. When evaluating the performance of language models in this context, does the language model simply mimic this knowledge or does it inherently possess it? One paradigm through which to formalize this is through a deeper categorization of common sense.

In particular, physical common sense, or knowledge about the physical world and its properties, is fundamental knowledge for realizing the world and the interactions within it. Physical common sense is a naturally multimodal concept, though, that for humans requires a combination of several senses to perceive, as physical properties are manifested in multiple modalities. A lack of info in any modality may make an object visually ambiguous, or otherwise manifest some misunderstanding of an object. Can we expand the capabilities of language models by imbuing them with multifaceted input to expand its knowledge base beyond text alone?

In this work, I focus on evaluating the physical commonsense reasoning ability of unimodal and multimodal models from text-based tasks under multimodal input. I specifically compare the performance of a text-only language model with a multimodal vision-language model and investigate (a) whether the multiple modalities of input in pretraining the multimodal model can have comparable performance to a text-specialized model, and (b) whether the supplementation of relevant image data at inference time boosts the performance of the multimodal model, compared to a previously text-only input.

Intuitively, vision data should benefit the physical commonsense reasoning of a model by providing the inputs the additional feature of a physical manifestation. Here, I investigate whether image data truly gives deep learning models an additional dimension of representation to benefit its commonsense reasoning.

Related Works

Several previous works evaluate language models on unimodal text-based commonsense reasoning. A number of common sense benchmarks for LMs exist, evaluating a variety of common sense categories

The intersection between text and vision in models has also been explored in several works, though not in the context of commonsense reasoning. For example, text-to-image models have shown significantly greater improvement in improving & expanding the text encoder as opposed to a similar increase in size of the image diffusion model

More generally, the effect of additional modalities of data on downstream performance is studied in Xue et al. 2022

Methods

Commonsense Benchmarks

It’s important to note that there are many distinguishing categories of commonsense knowledge. Physical common sense (e.g., a ball rolls down an incline instead of remaining still), social common sense (e.g., shouting at a person may incite fear), temporal common sense (e.g., pan-frying chicken takes longer than oven-roasting one), and numerical/logical common sense (e.g., basic arithmetic) are a few examples that all require different modalities of reasoning and may favor some models & architectures over others. Here I focus on physical common sense, since intuitively vision data may influence a model’s physical knowledge the most.

Commonsense benchmarks can be further categorized into (a) multiple-choice evaluation, where given a short background prompt, a model must select the most reasonable option or continuation from a set of given options, and (b) generative evaluation, where a model must generate an answer or continuation to the prompt. Here, I will focus on multiple-choice evaluation, as multiple-choice benchmarks provide a more concrete and reliable metric for determining similarity to “human” judgment. To evaluate the commonsense performance of both the unimodal and multimodal models, the HellaSwag benchmark is used.

HellaSwag

The HellaSwag benchmark

Here, for evaluating the multimodal model, I use only the entries generated from ActivityNet, as each ActivityNet prompt has an associated source ID from which the original source video may be accessed. From the video, image data can be scraped to augment the multimodal model’s fine-tuning and inference. The image data generation process is described in more detail in a following section.

Due to resource and time constraints, only a subset of this data was used for training and evaluation. Given the large size of the original HellaSwag benchmark, the sampled subset of the original data contains 10% of the original data. Each datum within the sampled dataset is sampled randomly from the original train/validation set, and each prompt within the sampled dataset is verified to have a publicly available video associated with it, i.e., the associated YouTube video is not private or deleted. Implications of this limitation are discussed further in the Limitations section below.

Text-Only Language Model

RoBERTa

RoBERTa

Vision-Text Multimodal Model

CLIP

The CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training) model is a multimodal vision and language model

In the experiments described below, the multimodal model is compared to the unimodal model via text sequence classification and text + vision sequence classification for determining the most likely ending to each HellaSwag prompt, so high baseline performance in both of these tasks is an essential starting point, which CLIP provides. Like for the RoBERTa model, a dropout layer and a linear classification head is used in conjunction with CLIP to perform the label classification for each prompt.

Image Data Generation

To collect the supplementary vision data for fine-tuning and evaluating the multimodal model, an additional scraping script is used to collect the relevant image data for each HellaSwag prompt. As described before, each prompt in the HellaSwag benchmark is generated from an associated ActivityNet prompt. Each ActivityNet prompt contains a source ID for the corresponding YouTube video, as well as a time segment containing the start and end time (in seconds) for the relevant video annotation. Using this information, each text prompt can be supplemented with an additional image prompt via a frame from the corresponding YouTube video.

A custom script is used to access each prompt’s corresponding YouTube video and scrape image data. The script works as follows:

- From a HellaSwag entry, obtain the source ID for the corresponding ActivityNet entry.

- From the ActivityNet entry, obtain the YouTube video source ID (to be used directly in the YouTube URL) and the time segment indicating the start/end time of the annotated clip.

- Download a low-resolution copy of the YouTube video via accessing the URL

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v={source_id}. Here, we download the 144p resolution copy of each video. - Capture a single selected frame from the video data. Note: the selected frame is determined by calculating the average between the video clip’s start and end time, then scraping the frame of the video at that timestamp. Implications of this frame selection are described in more detail in the Limitations section below.

- Save the frame as image data for multimodal fine-tuning.

This pipeline is used on the (sampled) HellaSwag train, validation, and test sets so that image data is available for both fine-tuning of the multimodal model, as well as inference for evaluation.

Experiments

Data

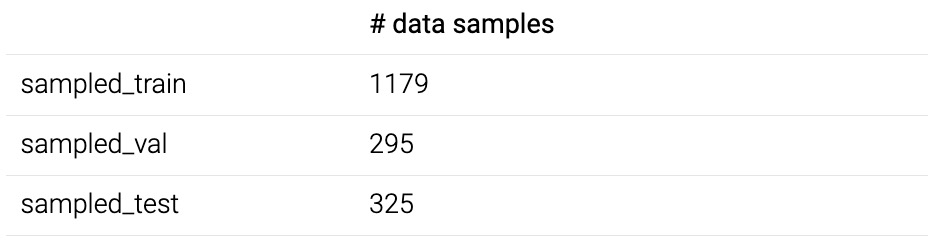

For fine-tuning and evaluation of the unimodal and multimodal models, a subset of the HellaSwag dataset is used, as already described above. Further summary of the sampled dataset can be found in Table 1.

To prepare the data for Multiple Choice Classification, the data from each prompt must be preprocessed as follows. Each prompt in the HellaSwag dataset is broken into three components: ctx_a, which contains the first sentence(s) of the prompt, ctx_b, which contains the initial few words of the final sentence, and four endings all stemming from the same ctx_a and ctx_b but each with different conclusions. This particular formatting of the data is important for the RoBERTa tokenizer, where each sequence within an inputted text pair must be a complete sentence. Each prompt then generates four text pairs of the form (ctx_a, ctx_b + ending_i) for each of the four endings. This allows for the multiple choice classification head to compute the most likely of the four endings, given the same context ctx_a, ctx_b.

Setup

The architecture of neither the RoBERTa nor CLIP are designed for sequence or multiple choice classification, so a separate linear classification head follows each of the unimodal RoBERTa, unimodal CLIP, and multimodal CLIP models.

Text-only fine-tuning: The training and validation sets for fine-tuning are formatted and preprocessed as described above. To adjust the weights of the classifier and the core embedding model, each model is fine-tuned on the HellaSwag training data and evaluated during training on the validation data for 20 epochs. Since only the text prompt is inputted to CLIP here, only the CLIP text embedding is used for classification.

Text-image fine-tuning: To fine-tune the multimodal CLIP model, the original training and validation datasets are augmented by adding each prompt’s relevant corresponding image data (from the process described in the Image Data Generation section). The multimodal model is then fine-tuned on both the text prompts as before and the relevant image data simultaneously. With both text and image input, CLIP outputs a combined text-image embedding that is used for the classification head, instead of the text-only embedding from before.

After fine-tuning, each model is evaluated on the withheld HellaSwag test dataset for classification accuracy. For both the text-only and text-image fine-tuning, I perform three total repetitions for each model and average the results in Figure 1.

Results

As shown in the accuracy results, the RoBERTa model performs the best, while the unimodal CLIP model performs worse, and the multimodal CLIP model only slightly better than the unimodal CLIP but still marginally worse than RoBERTa. RoBERTa likekly performs so well because of its generally high performance in other text-based tasks, and its bidirectional contextual embeddings allow for evaluation of a prompt/ending holistically. In this setup, the supplementary image data did not provide any significant empirical improvement to the multimodal model, as shown by the insignificant improvement in downstream performance when comparing the text-only to text-image CLIP models.

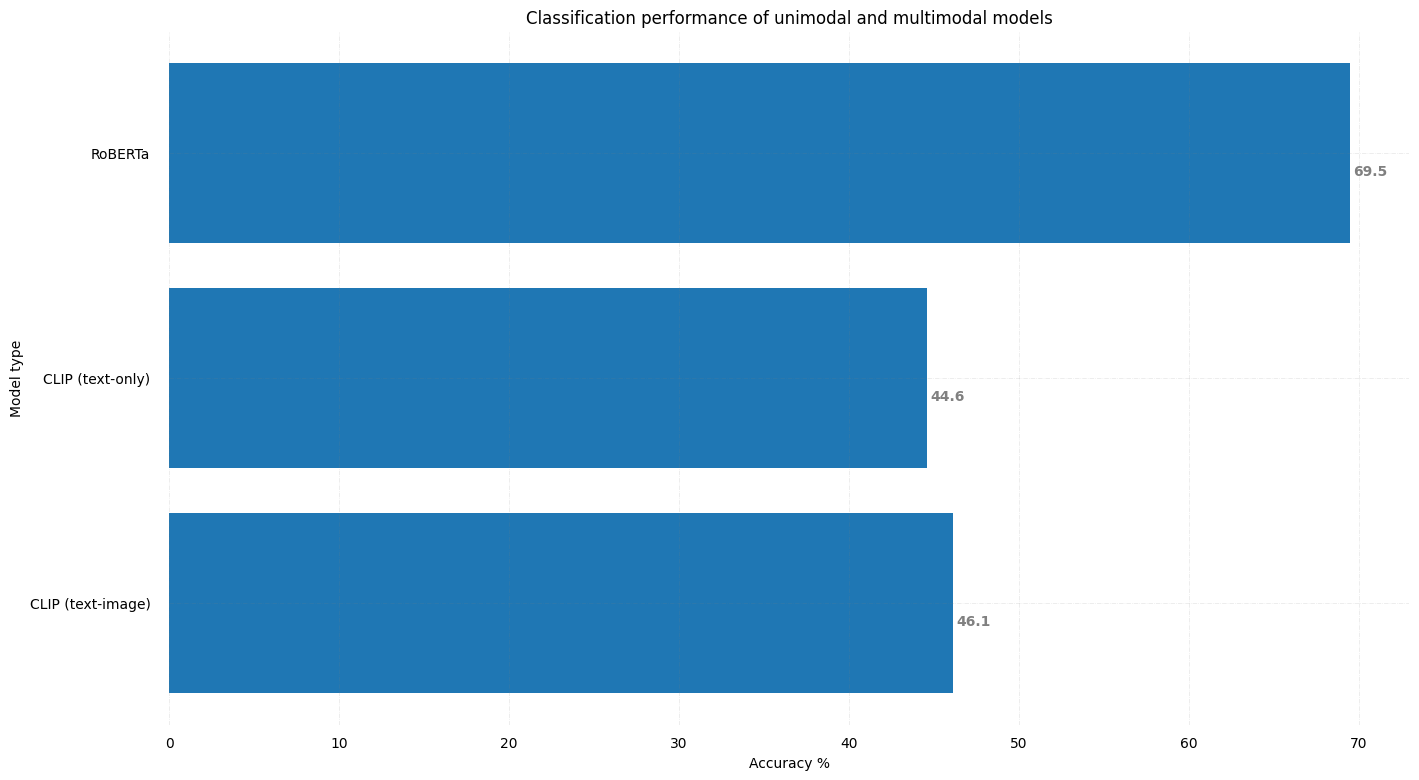

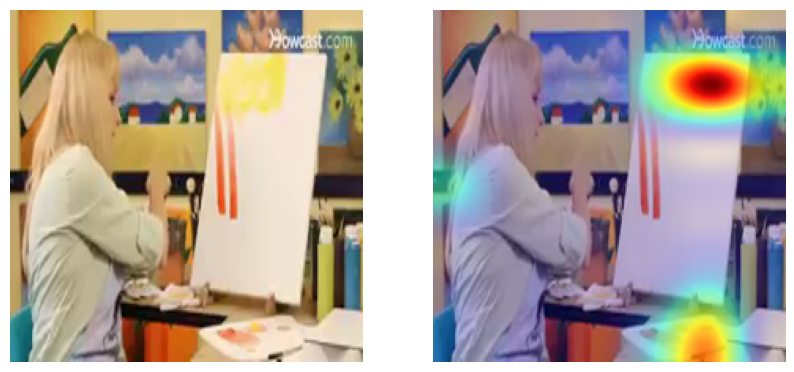

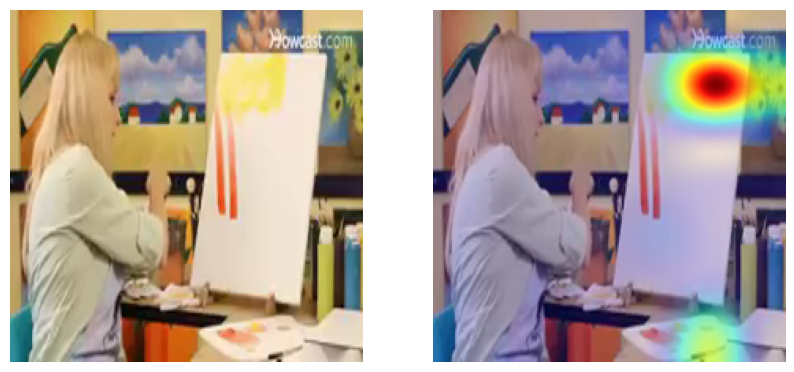

However, I attempt to provide an explanation for this shortcoming through further investigation of the supplementary images. Below, I display the class activation map of the image data from a particular prompt to attempt to visualize why the additional modality of data had little effect on the classification distinguishability across the four endings of the prompt. Figure 2 shows the image (which is the same for all four endings) and the individual image attention masks generated from each ending corresponding to the following context: A lady named linda, creator of paint along is demonstrating how to do an acrylic painting. She starts with a one inch flat brush and yellow and white acrylic paint. she ...

Notice that across all four prompt/ending pairs, CLIP attends primarily to the same location on the image. While the image data might enrich the model’s representation of the prompt itself, the similarity across the generated attention masks demonstrates that the image doesn’t serve to distinguish the endings from each other and, therefore, has little effect in influencing the likelihood of any particular ending from being more likely. In this setup, the text embedding alone determines the classifier output, and the lack of image distinguishing power provides some explanation for the similarity in downstream performance between the unimodal and multimodal CLIP models.

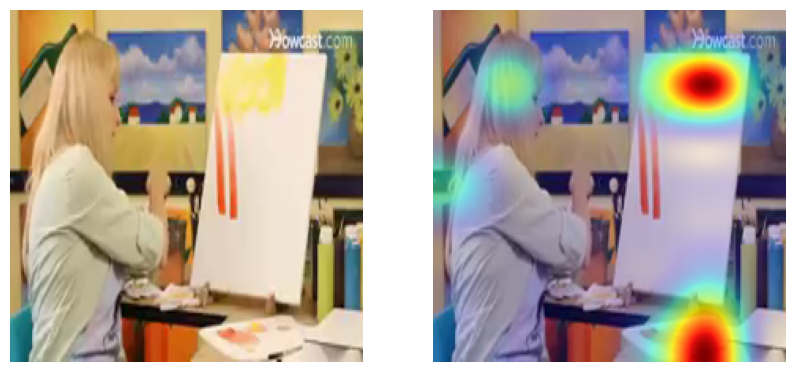

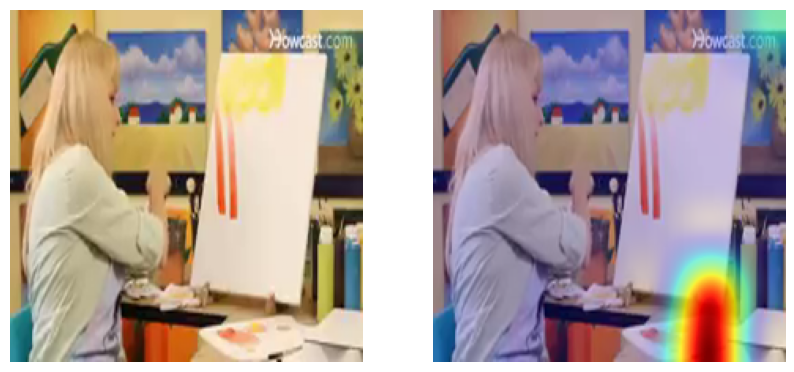

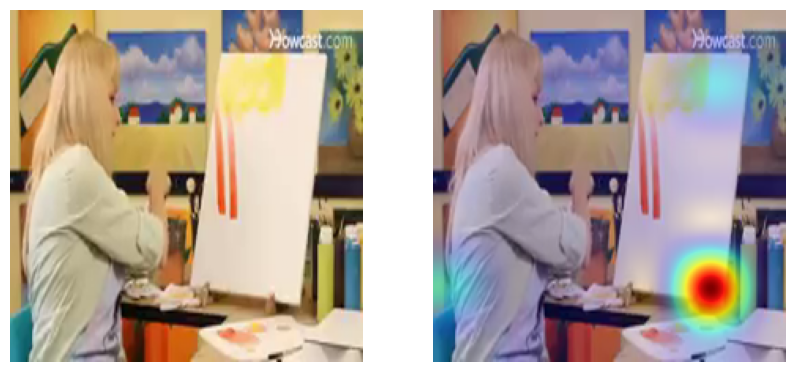

However, it’s possible that the attention masks were only so similar because all endings were prepended by the same exact context. In the case of Figure 2, the context describes an interaction with the painting, so it may be natural for all attention masks to focus on the painting, regardless of the conclusion of the ending. What if we restrict the image caption to contain only the final sentence (ctx_b + ending)? Figure 3 displays the class activation maps for this setup (though, not from an additional CLIP model fine-tuned on this image caption setup).

We see that using the final sentence without the preceding context generates more varied attention masks, so does this unconditionally allow for more diversity in the image/common sense representation in the joint text/image embedding? I claim that the answer is no; having the entire context for analysis is fundamental for common sense reasoning, so removing a significant portion of the context promotes greater ambiguity in both the intent of the prompt/image caption and the benefit of the attention mask. Using only the final sentence may produce more varied results in the image attention mask, but this may potentially be more detrimental than beneficial by attending to an irrelevant portion of the image that may detract from the commonsense ground truth answer.

Further investigation into different formulations of the image caption with respect to the original prompt in this manner may result in truly richer representations and more meaningful results for downstream model performance.

Conclusion

In this work, I compare the physical commonsense reasoning capbility of a text-only language model with a multimodal vision-language model and evaluate whether the multiple modalities of input in pretraining the multimodal model can have comparable performance to a text-specialized model, and whether the addition of relevant image data for inference boosts the performance of the multimodal model. I find that, within the proposed experimental setup, the effects of image data supplementation are insignificant, though I provide a potential explanation for this unintuitive result via class activation maps of the multimodal model’s image attention data; alternative formulations for this text-image data augmentation may provide better and more intuitive results. Overall, I provide an empirical experimental pipeline and analysis for potential factors toward further artifical intelligence models’ physical commonsense reasoning, and their internal representations of the world.

Ethical Implications

It’s also important to note the ethical considerations of “improving” the commonsense reasoning capabilities of deep learning models. Converging on a universally-accepted definition of common sense is utopian, so the interpretation of common sense evaluation must be constantly scrutinized. The biases and malicious elements of a model’s knowledge base must be investigated to ensure that fine-tuning on common sense benchmarks are not further accumulated and embedded into the model. Physical common sense is relatively simple for finding a ground truth answer or natural continuation, but for social common sense, for instance, what a model “should” predict for a particular situation or prompt is much more ambiguous.

Limitations

The implementation and constraints of this work imply some limitations. One evident limitation is the size of both the benchmark dataset and the models used. Evaluating uni- and multimodal models on the full HellaSwag benchmark, including all of both ActivityNet and WikiHow entries, may conclude in slightly different results. Furthermore, newer and bigger models for both text and vision-text models exist; for example, if evaluation is extended to generative prompt evaluation, the recently released GPT4 model

On the topic of generative prompt evaluation, this work only uses multiple-choice prompts for the simplicity and clarity of its evaluation results. However, generative prompts may more closely reflect human-generated responses and may be more representative of multimodal capabilities. Finally, making progress toward a more general-purpose intelligent system means extending the common sense evaluation to more categories than physical. Designing a more comprehensive multimodal model for common sense requires evaluation on all modalities of common sense, and will likely also require additional modalities of input data (e.g., audio cues for better social common sense performance).