Increasing Context Length For Transformers

How can we make attention more efficient?

Introduction

Since its release on November 30, 2022, ChatGPT has assisted users around the world with a variety of document parsing and editing tasks. These tasks often require large input contexts, since the documents and texts passed into ChatGPT’s source model, GPT-3.5, can be several pages long.

Like many other language models, GPT-3.5 is a unidirectional transformer that uses the self-attention mechanism. But while self-attention is an extremely powerful mechanism, it is also expensive in its time and space complexity. Standard self-attention requires $O(n^2)$ operations in terms of the sequence length $n$, since the $QK^T$ term within the attention mechanism calculates and stores the attention of each of the $n$ tokens with $O(n)$ other tokens.

Unfortunately, the $O(n^2)$ complexity makes long input contexts difficult for transformers to handle efficiently. Over the past few years, researchers have been investigating ways of mitigating the $O(n^2)$ factor. This remains an ongoing problem, with several papers released on the topic in 2023 alone.

Literature Review

In the past, large context lengths were handled using a simple partition scheme. Essentially, long inputs can be split into fixed-length chunks, where attention is computed separately for each chunk. Then, for chunk size $b$, a sequence of length $n$ requires only $O\left(\frac{n}{b} \cdot b^2\right) = O(nb)$ time to compute. However, this method has a major drawback in that information cannot be shared across partitioned blocks, leading to the fragmentation problem: the model lacks long-term dependencies and thus runs into cases where it lacks the necessary context to make accurate predictions.

Modern methods for reducing context lengths in transformers generally try to avoid this problem by either introducing ways of sharing context across partitions or reducing self-attention calculation cost by using a simpler approximation. Models that fall into second category may utilize one of many different approximation techniques, such as sparse attention matrices and fixed attention patterns.

Sparse Transformer

Child et al. proposed a sparse transformer that reduces attention calculation cost from $O(n^2)$ to $O(n\sqrt{n})$.

One attention head processes a local window of size $k$ surrounding the current token $i$, while a second attention processes tokens $j$ such that

\[(i - j) \mod l = 0 \qquad \forall j \leq i,\]where $l$ is a parameter chosen to be close to $\sqrt{n}$. Since only $O(l)$ tokens are attended upon for each token $i$, this results in the $O(n \cdot l) = O(n\sqrt{n})$ runtime. Child et al. showed that the sparse transformer can be applied to a wide range of fields, including image, text, and music, where it can be used to possess audio sequences over 1 million timestamps long.

Longformer

Longformer<CLS> token to the start of every input in classification tasks. Despite using sparse attention contexts, Longformer was able to outperform state-of-the-art model RoBERTa on several long document benchmarks.

BigBird

BigBird

- Global attention, consisting of tokens that attend upon every other token

- Local attention, consisting of a sliding window around each token

- Random attention, consisting of randomly-selected tokens

Using this architecture, BigBird managed to increase maximum transformer context lengths by up to 8x. In the same paper, Zaheer et al. proved that certain sparse transformers are computationally equivalent to transformers with full attention. Theoretically, sparse transformers are capable of solving all tasks that full transformers can solve; this explains why sparse transformers are often a good approximation for full transformers.

TransformerXL

TransformerXL differs from the previously discussed models, as it doesn’t increase self-attention efficiency by sparsifying the attention matrix.text8, Penn Treebank, and WikiText-103.

Landmark Tokens

More recently, Mohtashami et al. suggested using landmark tokens to determine which tokens should be attended to.

VisionTransfomer

Most of the models discussed above apply specifically to transformers used for language modeling. However, algorithms for reducing attention complexity have been successfully used for other tasks as well. For example, VisionTransformer managed to achieve SOTA performance while limiting the attention context to a 16x16 patch around each pixel.

Hardware Methods

Aside from algorithm-based techniques, there have also been attempts to make basic transformer algorithms run faster on existing hardware. Although sparse attention algorithms may have better time complexity, they may not achieve practical speedups due to hardware inefficiencies. In order to achieve practical speedups on transformer training, Dao et al. proposed FlashAttention, an I/O-aware attention algorithm that implements the basic attention computation.

Other Methods

Numerous other algorithms for extending transformer context lengths have been proposed, including retrieval-based methods

Methodology

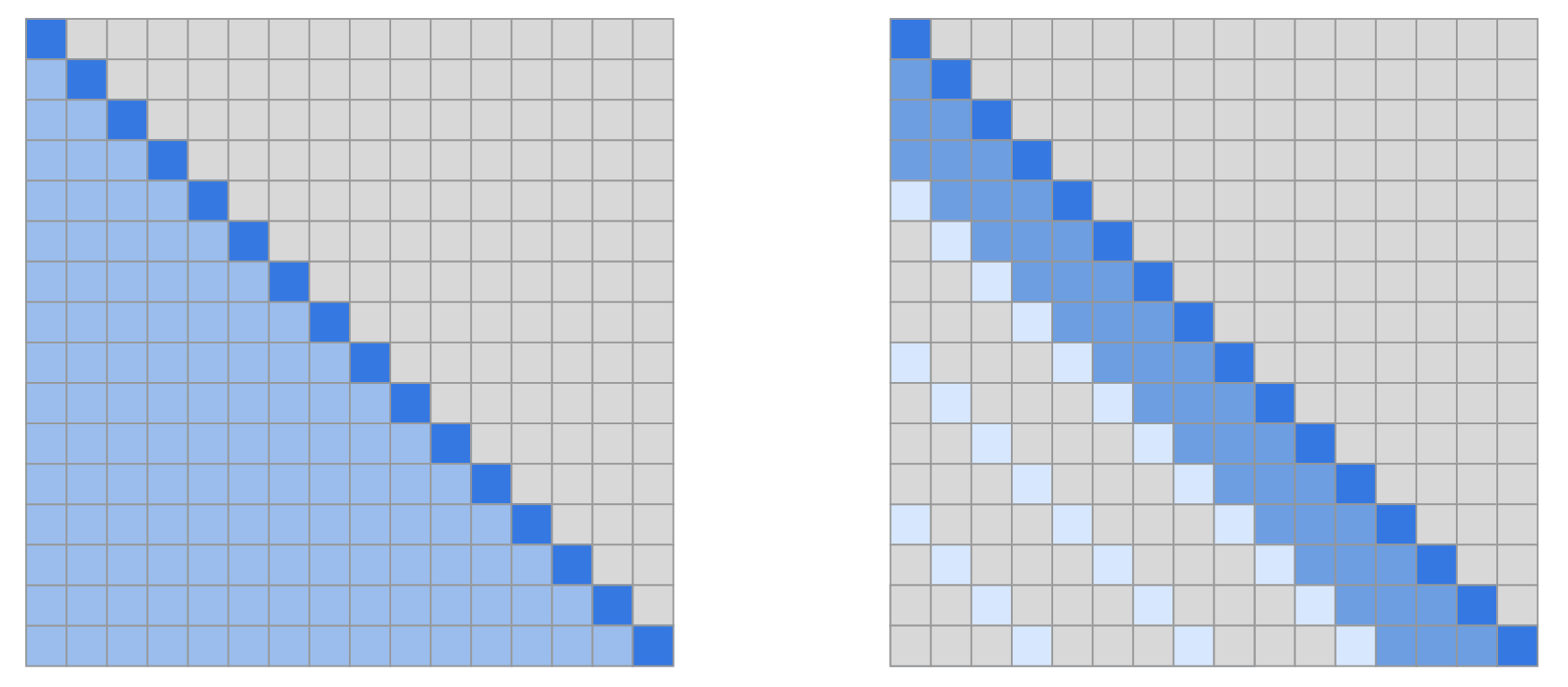

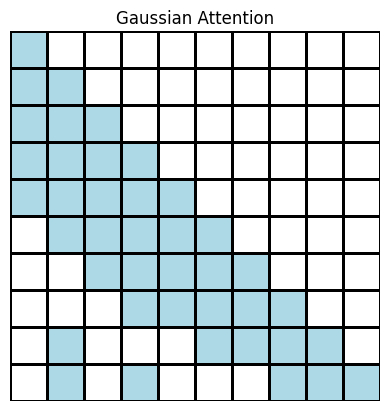

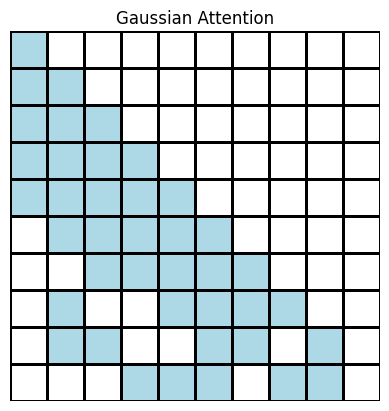

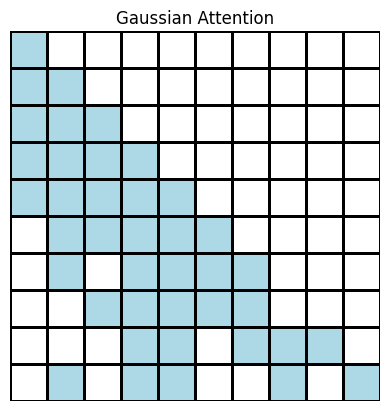

To see what types of context reduction algorithms are effective, we propose and test our own efficient transformer. We investigate whether transformers using Gaussian-distributed fixed attention patterns can perform as well as standard transformers. For each self-attention layer, we sample a Gaussian random distribution to determine which elements of the attention matrix we should compute. We analyze this approach for the unidirectional language modeling case, where the goal is to predict the next token of a given input sequence.

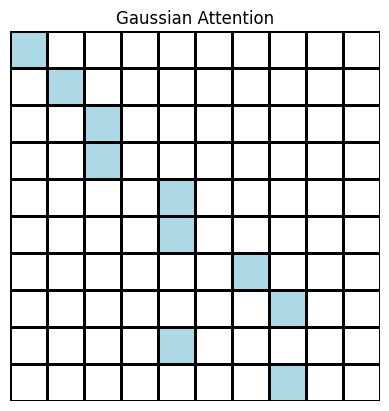

In language modeling, the most important context for predicting a new token often comes from examining the tokens that immediately precede it. Previous work has taken advantage of this pattern by employing fixed local attention patterns, such as the sliding window pattern used by BigBird. For token $i$, random samples from a truncated Gaussian distribution with mean $i$ and standard deviation $\sigma = \frac{\mu}{2} = \frac{i}{2}$

On the other hand, it may also be possible that some distant token $j$ has a large impact on the prediction of token $i$. For example, if you pass in a document in which the first sentence defines the overall purpose of the document, we might need to pay attention to this sentence even in later sections of the document. Fixed-pattern Gaussian attention allows for this possibility by calculating attention scores for $i$ and distant tokens $j$ with a lower but still nonzero probability. As a result, Gaussian attention offers some flexibility that may not be present in other fixed-pattern attention mechanisms, such as the sliding window technique.

Algorithm

The model takes a hyperparameter $c$, where $c$ is the number of tokens that each token attends upon. For every token $i$ in each self-attention layer, we select $c$ tokens from the Gaussian distribution $\mathcal{N}(i, i/2)$, where $\mathcal{N}$ is truncated at $0$ and $i$. Since our task focuses on the casual language modeling case, a token $i$ computes attention scores only for tokens $j<i$. Truncation ensures that every $i$ attends to exactly $\min(c, i)$ tokens.

for each token i:

sample min(c, i) values from N(i, i/2)

create list of indices by flooring every sampled value

remove duplicates assigning duplicates to the nearest unused index

# such an assigment always exists by pigeonhole principle

For each token $i$, we set all attention values for tokens which are not selected to zero. As a result, each token attends only on at most $c$ tokens, leading to an overall cost of $O(c \cdot n) = O(n)$ for constant $c$.

Experiments

Since we had limited training resources, we unfortunately couldn’t test Gaussian attention on large models like BERT or GPT. Instead, we used a toy study involving small models with smaller inputs—this leads to some additional considerations in analyzing our results, which we address later.

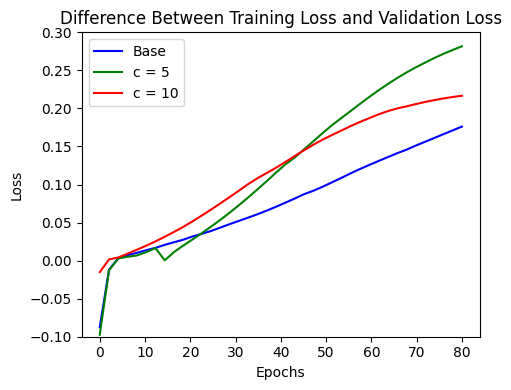

We first tested whether models trained with limited Gaussian attention can achieve similar performance as models that were trained on full self-attention. We trained models with $c = 5$ and $c=10$ and compared them to the performance of the base model. For our base experiments, we used three self-attention heads per layer and six layers in total.

Our evaluation metric for all models was next-token cross-entropy loss against a corpus of Shakespeare texts.Training is optimized with Adam and a learning rate of 0.0001.

Base experiment results are shown below.

| Model | Epochs | Training Loss | Validation Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 80 | 4.2623 | 4.4390 |

| Base | 130 | 3.7709 | 4.0320 |

| Base | 140 | 3.7281 | 3.9964 |

| $c = 5$ | 80 | 3.7458 | 4.0355 |

| $c = 10$ | 80 | 4.1619 | 4.3801 |

We found that both the $c=5$ and $c=10$ models were able to achieve similar performance as the base model, which suggests that Gaussian attention may be a good approximation for full attention. Interestingly, both Gaussian models required significantly fewer epochs to reach the same performance as the base model. Both Gaussian models also demonstrated faster separation between training and validation losses. We hypothesize that the smaller attention context helps focus learning on more relevant tokens, which lowers the number of training epochs needed. As a result, the model is able to learn the language modeling task more rapidly, leading to faster overfitting.

Although initial results were promising, we chose to investigate a few factors that could have inflated model performance.

In order to determine whether the Gaussian attention models are affected by input length, we tested the same setups with longer inputs. Our base experiments used relatively small inputs, each corresponding to one piece of dialogue in a Shakespeare script. On average, these inputs were approximately 30 tokens long; with $c = 5$, the selected context may be more than $\frac{1}{6}$ of the total tokens. As a result, Gaussian model accuracy might be inflated for small inputs, since the context essentially covers a large portion of existing tokens. To make $c$ a smaller fraction of the input length, we modified the dataset instead to create inputs with an average length of 100 tokens. We summarize the results in the table below.

| Model | Epochs | Training Loss | Validation Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 90 | 5.5906 | 5.6207 |

| $c = 5$ | 90 | 5.5769 | 5.6166 |

| $c = 10$ | 90 | 5.6237 | 5.6565 |

With the longer input contexts, all three models had worse performance when trained for the same number of epochs. However, both Gaussian models managed to achieve approximately the same loss as the original model. This again suggests that Gaussian attention is a valid approximation of the standard attention matrix.

We further investigated whether the performance of the Gaussian models degraded rapidly when using a smaller number of layers and attention heads. Logically, increasing the number of attention heads would help mask bad attention patterns formed by the Gaussian sampling strategy. For example, although the sampling process selects tokens $j$ near token $i$ with high probability, it is possible that some attention head $x$ does not select the relevant tokens for a token $i$. With the addition of more attention heads, a different head may compensate for the bad head by operating on the correct tokens. Increasing the number of attention layers similarly increases the number of attention heads, where good heads can compensate for bad ones. Experiments showed that even with one layer and one attention head, the Gaussian models were able to achieve approximately the same performance as the base model.

| Model | Input Type | Epochs | # Heads | # Layers | Training Loss | Validation Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Short | 80 | 1 | 1 | 5.1009 | 5.1605 |

| Base | Long | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.5994 | 5.6289 |

| Base | Long | 90 | 1 | 6 | 5.5906 | 5.6207 |

| $c = 5$ | Short | 80 | 1 | 1 | 5.0481 | 5.1139 |

| $c = 5$ | Long | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.5884 | 5.6273 |

| $c = 5$ | Long | 90 | 1 | 6 | 5.5769 | 5.6166 |

| $c = 10$ | Short | 80 | 1 | 6 | 4.5597 | 4.6949 |

| $c = 10$ | Short | 90 | 1 | 6 | 4.5432 | 4.6809 |

| $c = 10$ | Long | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.6345 | 5.6666 |

| $c = 10$ | Long | 90 | 1 | 6 | 5.6237 | 5.6565 |

However, we noticed that with fewer heads and layers, the base model trained at approximately the same rate as the Gaussian model. A smaller number of attention heads and attention layers implies that fewer parameters need to be updated to learn the task; this typically means that training is faster for smaller models. As a result, it makes sense that a smaller model would benefit less from the increase in training speed that reduced attention context offers; since the model is so small, training is already fast and any decrease in training speed would be minor.

To test the limitations of Gaussian attention, we experimented with extremely sparse attention patterns that selected only one token for each model.

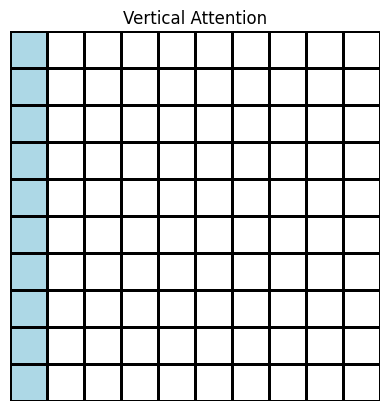

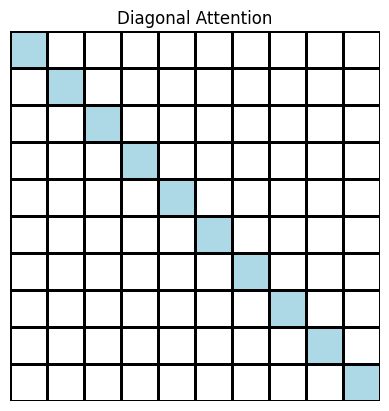

Although these models did not perform as well as the base transformer, we found that the token that was attended upon made a significant impact on the final loss. As shown in the table below, the models that employed a diagonal or Gaussian attention pattern performed significantly better than the model that used a vertical attention pattern on the first token. This suggests that local attention patterns were the most important ones for improving the outcome of our task; as a result, Gaussian attention may perform well specifically because it emphasizes the local attention context.

| Model | Epochs | # Layers | # Heads | Training Loss | Validation Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagonal | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.5089 | 5.5400 |

| Vertical | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.6652 | 5.6906 |

| Gaussian | 80 | 1 | 6 | 5.3231 | 5.3744 |

Implications and Limitations

Our experiments showed that Gaussian attention has potential as an algorithm for improving transformer efficiency and increasing context lengths. We note that these experiments may not reflect the algorithm’s actual performance in real-world scenarios. Because we did not have the capacity to train a language model on the scale of BERT or GPT, we experimented only with much smaller models that processed much smaller contexts. As a result, our experimental results may not extend to larger models. Additionally, due to limited training time, we did not train any of the models we used for more than 150 epochs; with more training time, it is possible that the base transformers may outperform the modified ones. In order to generalize to larger models, Gaussian attention may need to be combined with other attention patterns, like global attention. More research is needed to fully understand its potential and shortcomings.

Conclusion

Today, methods for increasing context length in transformers remains an important research topic. Although researchers have proposed numerous efficient transformers and self-attention algorithms, a concrete solution for increasing transformer context lengths has yet to be found. With recent developments in large language models, the number of tasks that transformers can be applied to is increasing rapidly. As a result, the search for an efficient transformer is more important than ever.

Our work shows that Gaussian distributions can potentially be used to build fixed-pattern attention masks. However, the performance of Gaussian attention masks in larger models remains to be confirmed and requires further study.