Can CNN learn shapes?

One widely accepted intuition is that Convolutional Neural Networks that are trained for object classification, combine low-level features (e.g. edges) to gradually learn more complex and abstracted patterns that are useful in differentiating images. Yet it remains poorly understood how CNNs actually make their decisions, and how their recognition strategies differ from humans. Specifically, there is a major debate about the question of whether CNNs primarily rely on surface regularities of objects, or whether they are capable of exploiting the spatial arrangement of features, similar to humans.

Background

One widely accepted intuition is that Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) that are trained for object classification, combine low-level features (e.g. edges) to gradually learn more complex and abstracted patterns that are useful in differentiating images. Stemming from this is the idea that neural networks can understand and use shape information to classify objects, as humans would. Previous works have termed this explanation the shape hypothesis. As

… the network acquires complex knowledge about the kinds of shapes associated with each category. […] High-level units appear to learn representations of shapes occurring in natural images

This notion also appears in other explanations, such as in

Intermediate CNN layers recognize parts of familiar objects, and subsequent layers […] detect objects as combinations of these parts.

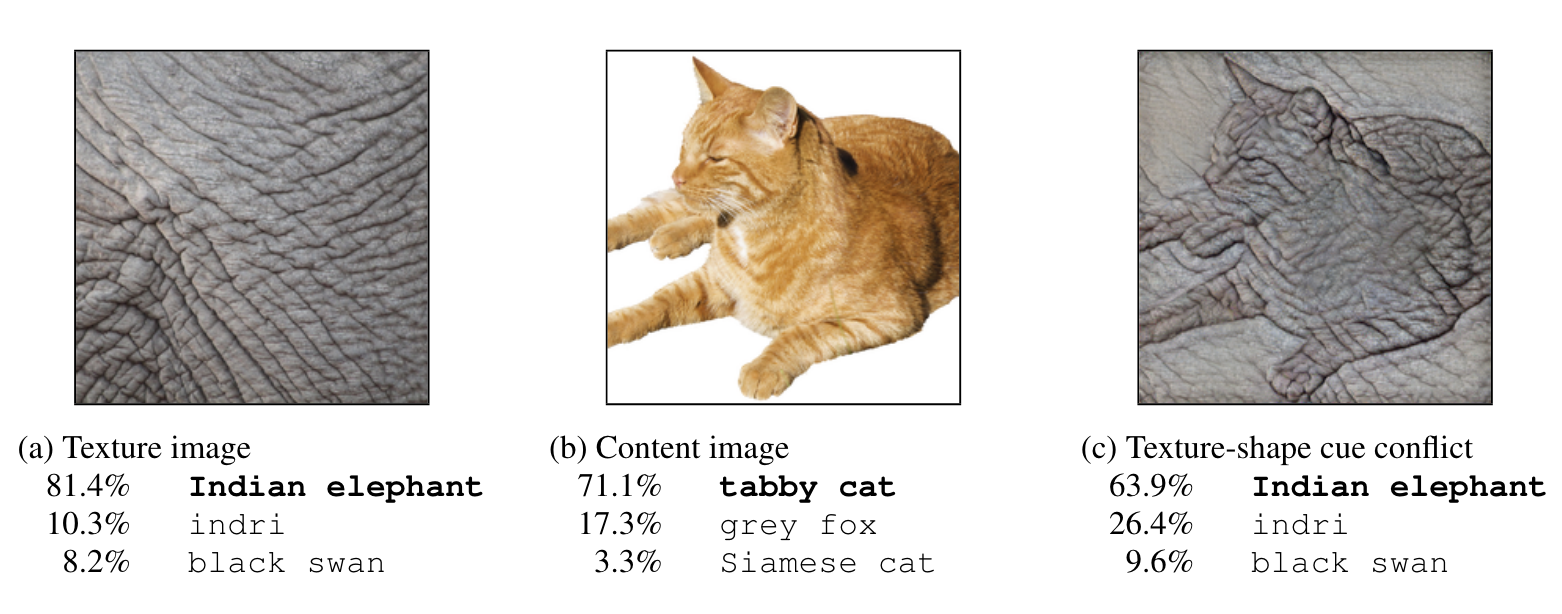

Figure 1.

Yet it remains poorly understood how CNNs actually make their decisions, and how their recognition strategies differ from humans. Specifically, there is a major debate about the question of whether CNNs primarily rely on surface regularities of objects, or whether they are capable of exploiting the spatial arrangement of features, similar to humans. Studies have shown that the extent to which CNNs use global features ; shapes or spatial relationships of shapes, is heavily dependent on the dataset it is trained on.

Motivation

The question leading this project is if it is possible to steer the learning of a CNN network to use abstracted global shape features as dominant strategy in classifying images, in a similar sense that humans do. Previous works have shown that networks trained on

Methods

In the following experiments, I train a CNN on human-generated sketch data and test with conlfict sets to determine if it has learned to integrate global features in its decision making. The objective is to push the network to learn and depend on global features (the overall shape) of the object rather than local features (direction or curvature of strokes) in classifying images. To do this, I first vary the filter sizes to see if there is an opimal sequence that enables the network to learn such features. Next I augment the data by fragmentation and by adding a false category so that the network is forced to learn to classify images even when the local information is obscured and only when global information is present. Finally, to test the ability of the models from each experiment in integrating the global feature, I design a conflict set that is different from the training data. Images in the conflict set have the global features (overall shape) that aligns with its category but the local features (strokes and corner conditions) are distorted to varying degrees.

Training Data

The first way that the model is pushed to learn global features is by training it on human generated sketch data. This is distinct from the previous works that have used stylized image data, or image data that has been turned in to line drawings in that it is more driven by the human perception. It is likely that the data is more varied because it is each drawn by a different person, but what humans perceive as distinctive features of that object category is likely to be present across instances.

The hypothesis is that because of the scarsity of features, and absense of other local features such as texture, the model would inevitably have to learn global features that humans commonly associate to object categories, such as shape.

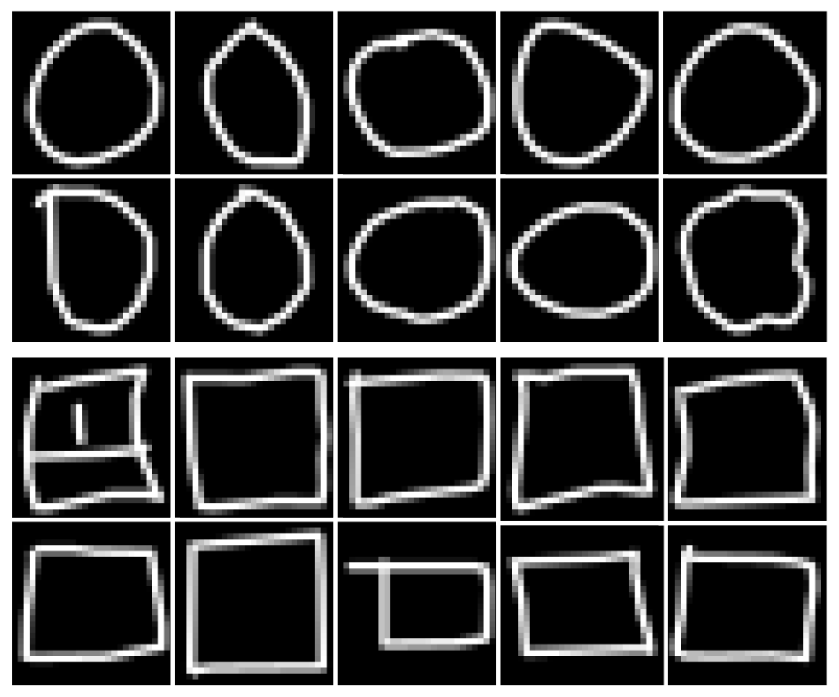

Figure 2. Example from circle and square category of Quick, Draw! dataset that are used in this project.

For the following experiments I use 100,000 instances each from the circle and square categories of the Quick, Draw! dataset that have been rendered into 28x28 grayscale bitmap in .npy format. The dataset is split 85% for training and 15% for validation.

Architecture and Training Hyperparameters

The CNN architecture is composed of 3 convolution layers and 2 linear layers with max pooling and relu activation. The filter size of each convolution layer, marked as * is varied in the following experiments. We use cross entropy loss and accuracy is the portion of instances that were labeled correcty. Each model is trained for 20 epochs with batch size 256.

nn.Sequential(

data_augmentation,

nn.Conv2d(1, 64, *, padding='same'),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2),

nn.Conv2d(64, 128, *, padding='same'),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2),

nn.Conv2d(128, 256, *, padding='same'),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2),

nn.Flatten(),

nn.Linear(2304, 512),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(512, 2), # 2 categories (circle, square)

)

Convolutional Layer Filter Size

The hypothesis is that the size of the filters of each convolution layer affects the scale of features that the network effectively learns and integrates in its final decision making. The underlying assumption is that if the filter size gradually increases, the CNN learns global scale features and uses that as dominant stragety. I test for different combinations of size 3,5,7,9 to see if there is an optimal size filter to train a CNN network for our purpose.

Data Augmentation - Fragmentation

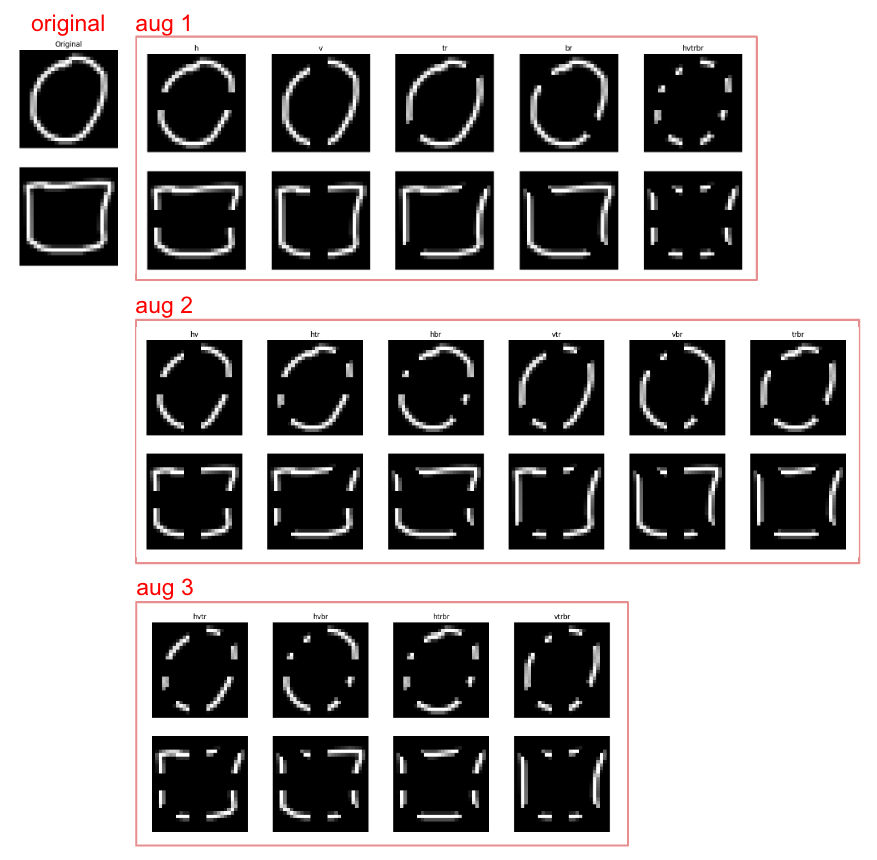

I train models with augmented data of different degree of fragmentation. Lower degrees of fragmentation divide the shape into 2 fragments and with higher degree, the shape is divided into an increasing number of parts. I do this by using masks that create streaks going across the image each in the horizontal, vertical and two diagonal directions. As a result, we create circles and squares with dashed lines.

Figure 3. Augmentations with varying degrees of fragmentation.

The hypothesis is that fragments of circles and squares may be similar, so as the network is trained to distinguish between two categories regardless, it has to gain an understanding of larger scale features ; how these line segments are composed. If the model successfully train on datasets that are highly fragmented, it is expected to acquire knowledge of global features. For instance, intermediate scale understanding interpretation of circles would be that the angle of line segments are gratually rotating. On the otherhand squares would have parallel line segments up to each corner where ther is a 90 degree change in the angle.

Data Augmentation - Negative Labels

We add instances where the local features of the circle or square is preserved, but the global feature is absent and labeled them as an additional category, ‘false’. We create this augmentation by masking half or 3/4 of the existing data. The intention here is to have the model learn to only categorize shapes when their global features are present.

Figure 4. Augmentation with addition of ‘false’ category.

Results

Training Evaluation

We first want to examine if the independent variables affect the model’s training on the classification task. There is the possibility that with certain filter sizes, the model may not be able to encode enough information to differentiate circles and squares. More likely there is a possibility with the augmentations that we are using to force the CNN to learn a more difficult strategy, where the model fails to train to classify instances similar to the training set to start with. If training the model is unsuccessful, it means that CNNs under those conditions are incapable of finding any strategy to differentiate the two shape categories.

Conflict Set Evaluation

To test the networks ability to employ global features we borrow the approach of

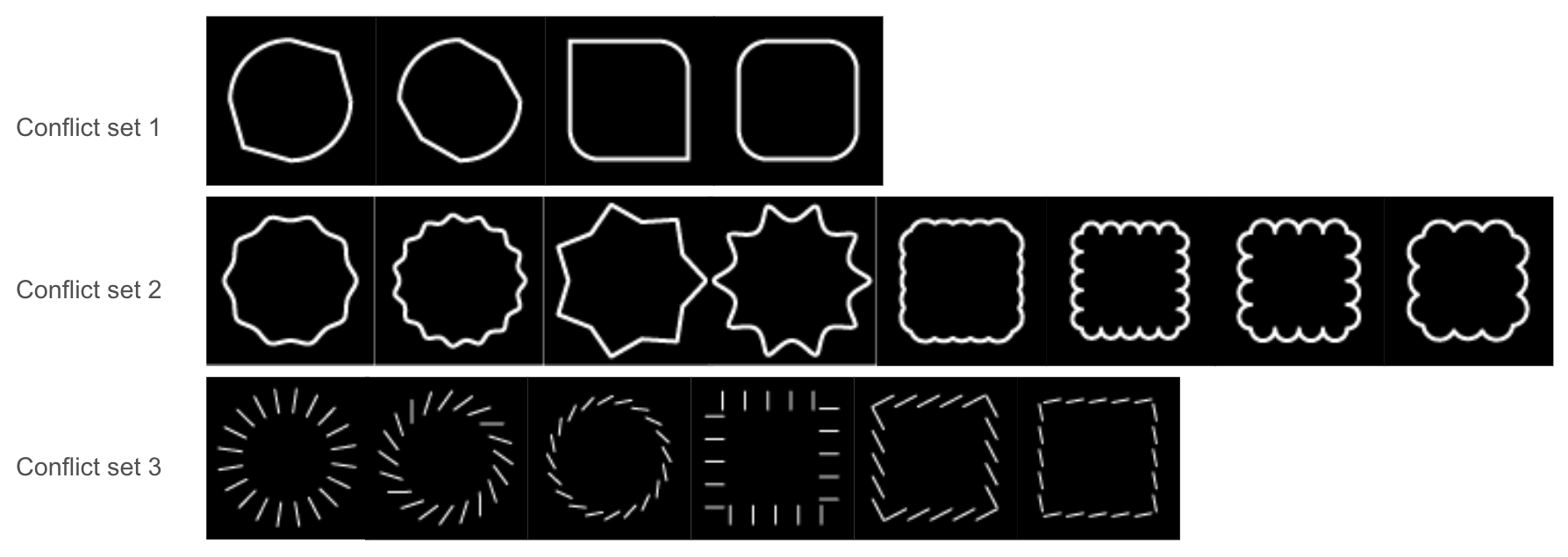

Figure 5. Three conflict sets that obscure local features to contradict the global feature and ground truth label.

We create three series of conflict sets for circle and squares that obscure its most distinguishing local features. The first set obscures the corner conditions - circles with one to two angular corners and squares with chamfered corners are included in this set. The second obscures line conditions - circles with angular lines and squares with curvy lines are created for this set. The third series targets the composition of strokes - instead of continuous lines, we use series of parallel lines of varying angles to form a circle or square.

Filter Variation

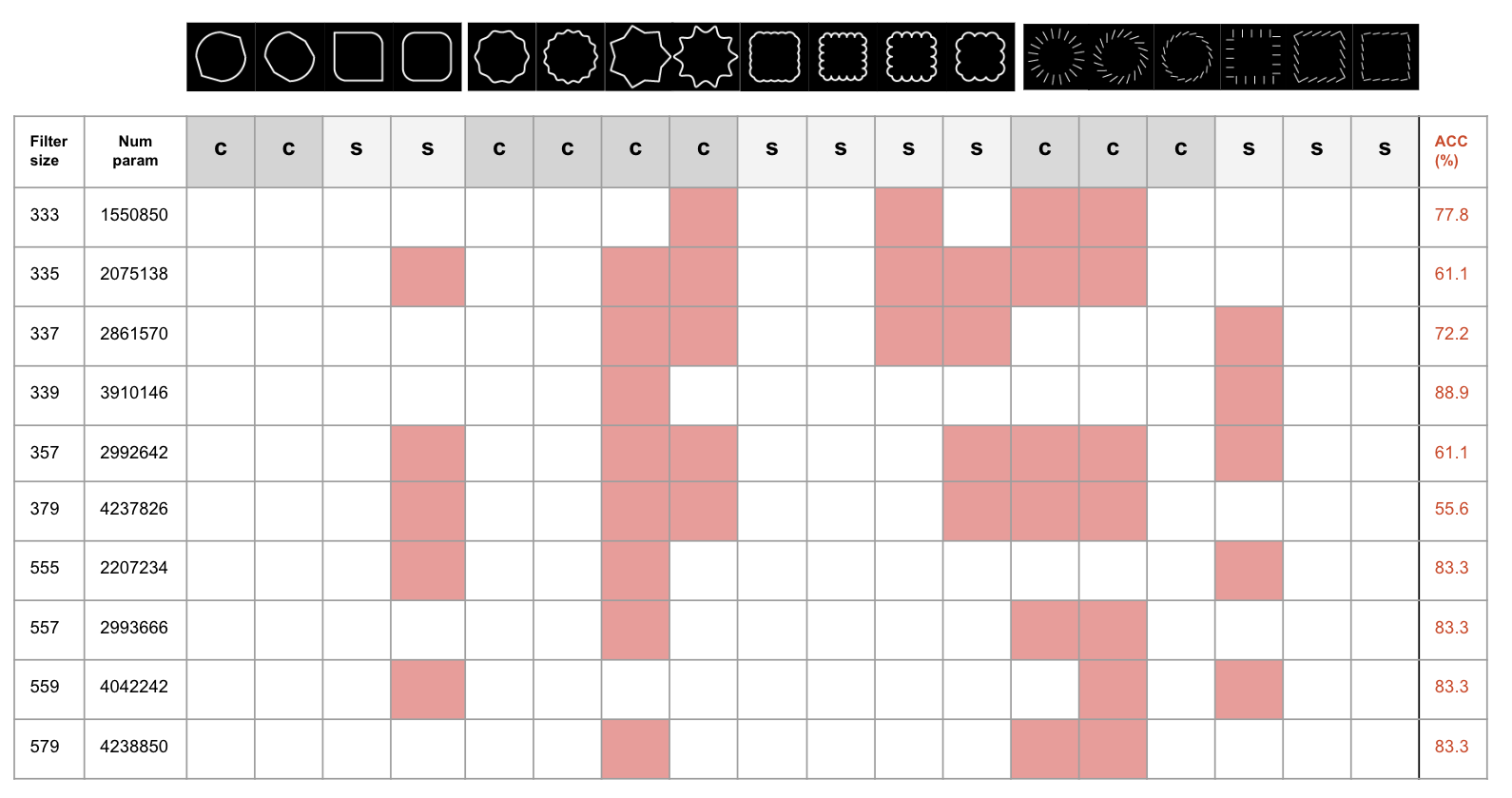

Figure 6. Training evalution for variations in filter size of the convolution layer.

For each variation in filter size, the models trained to reach over 98.5% accuracy on the validation set. Contrary to our speculation, the filter size did not largely affect the models ability to learn the classification task.

Figure 7. Evaluation with conflict set for variations in filter size of the convolution layer.

Overall we observe that having a large size filter at the final layer increases the model’s performance on the conflict set as with filter sequence 337 and 339. We can speculate that having consistantly smaller size filters in the earlier layers and only increasing it at the end (337, 339) is better than gradually increaseing the size (357, 379). However, this is not true all the time as models with consistant size filters performed relavitely well (333, 555). Starting with a larger size filter (555, 557, 579 compared to 333, 337, 379) also helped in performance. However, this also came with an exception where 339 performced better than 559.

Overall we can see that the models have trouble classifying instances with increased degree of conflicting local features. For instance the 4th instance in set 2 obstructs all four of the perpendicular angles of a square. The 3rd and 4th instance of set 2 have the most angular ridges forming its lines and the 7th and 8th instance of set 2 have the most circluar forming its lines. From set 3, the first and second instance obstruct the gradually changing angle of strokes within the circle the most.

Data Augmentation Variation

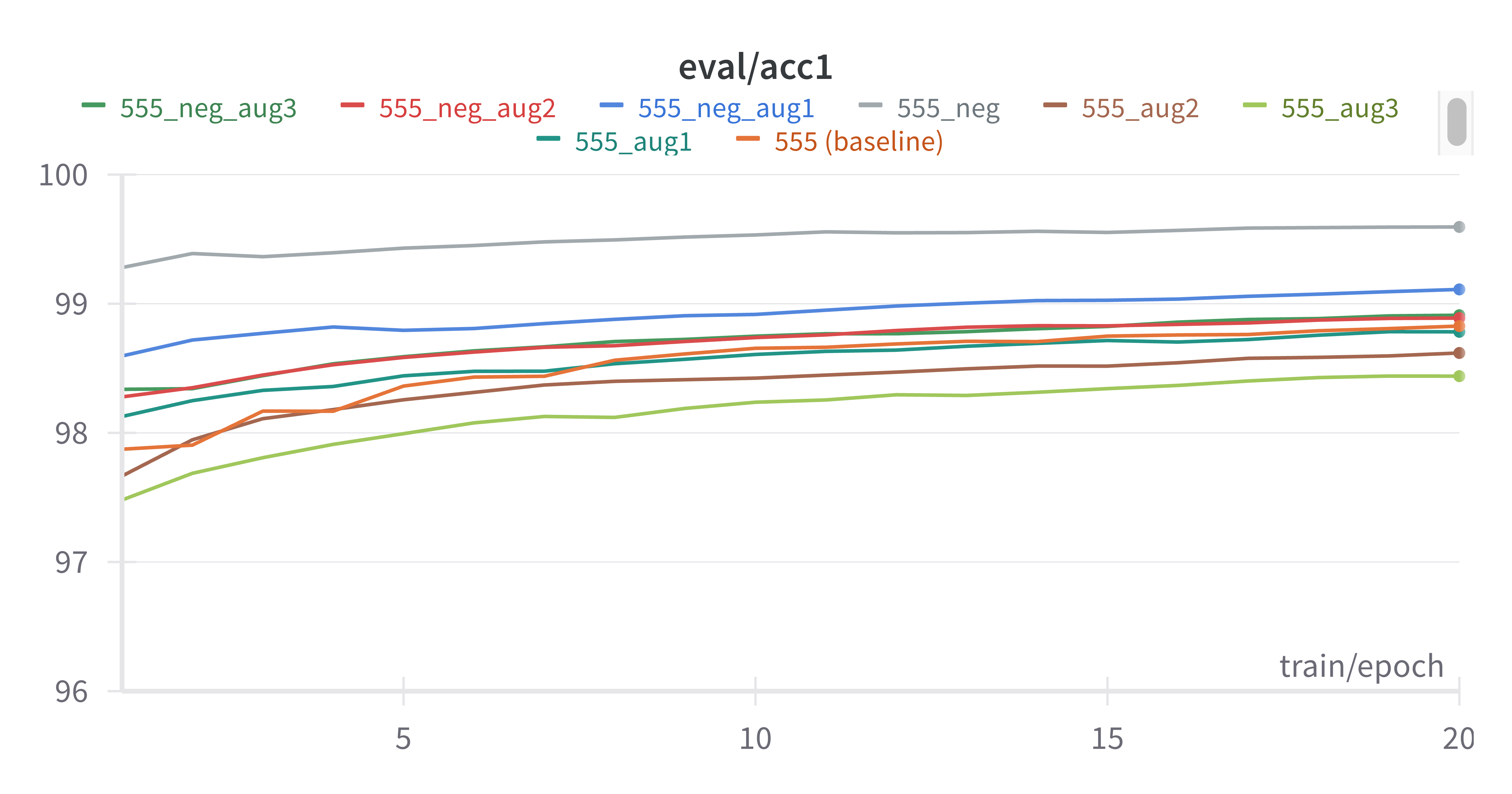

Based on the results with filter variation, we choose the filter size 555 to that performed moderately well, but still has room for improvement for the next experiment with augmented training data.

Figure 8. Training evalution for variations in augmentation of training data.

All models trained to reach over 98% accuracy on the validation set. As we speculated, the model had more difficulty in training with the augmentation as opposed to without. With the additional third negative category, the model was easier to train. This is evident with the divide in the plot with datasets that were augmented with the negative category to have higher evaluation values than the baseline and those that were only augmented with fragmented data were below the baseline.

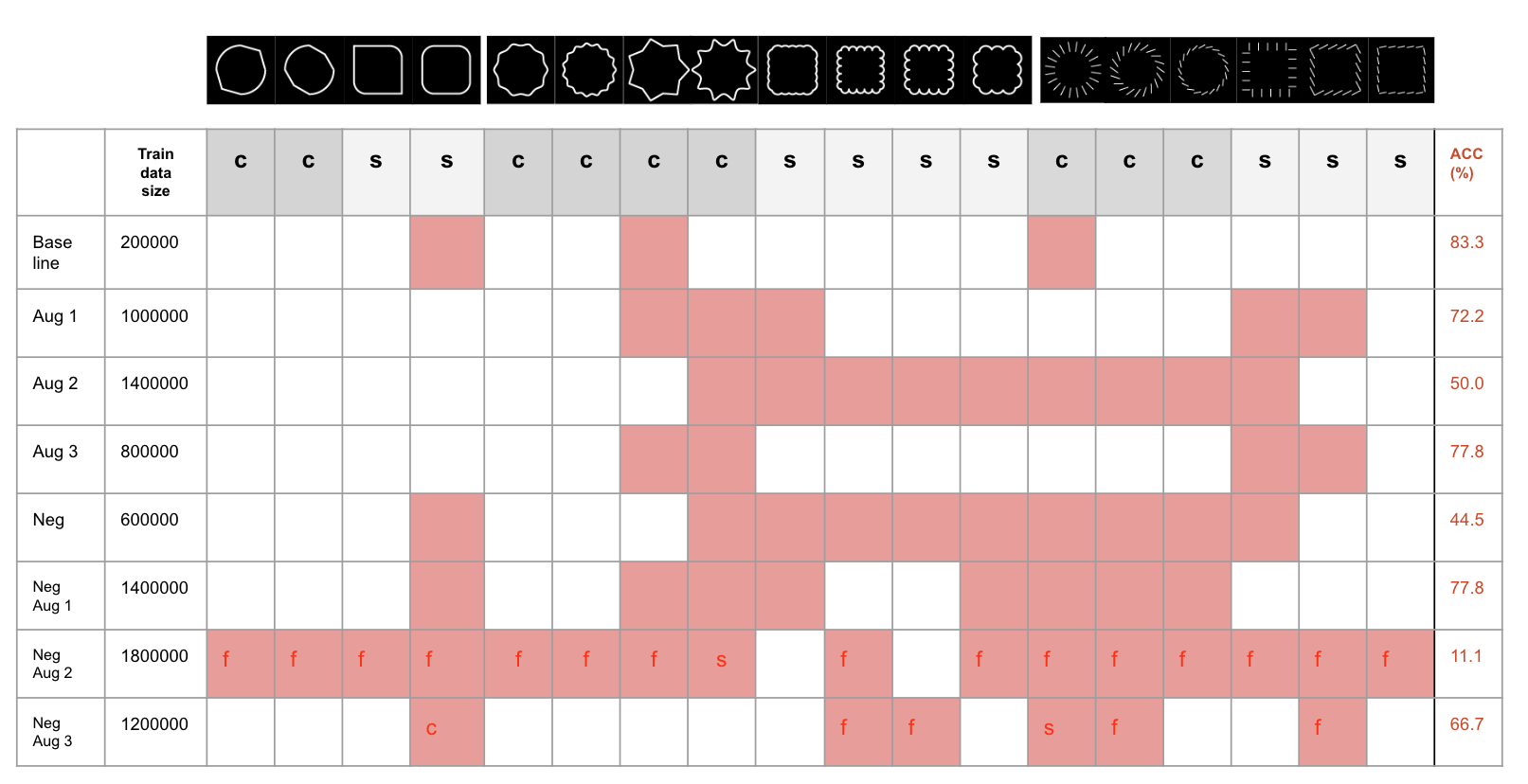

Figure 9. Evaluation with conflict set for variations in augmentation of training data.

The performance of models trained with augmented data on the conflict set was worse than that trained only on the original data which proves our initial hypothesis that it would be possible to enforce the network to use global features with augmented data wrong. What is interesting is how difference augmentations affect the performance. Initially, we thought that with the increased degree of fragmentation in the augmentation, the model would learn global features better, and would perform better on the conflict set. However comparison among the augmentation variations, Aug 2 showed significanly poor performance. Adding a ‘false’ category did not boost the performance either. What is interesting is that the misclassification does not include the false label. We speculate that the model has learned to look at how much of the image is occupied.

Conclusion

The experiments in this project have shown that there isn’t an obvious way to steer CNN networks to learn intended scale features with filter size variation and data augmentation. While it was difficult to find a strict correlation, the variation in performance across experiments shows that the independent variables do have an affect on the information that the network encodes, and what information reaches the end of the network to determine the output. The fact that trained models were unable to generalize to the conflict set reinforces the fact that encoding global features is difficult for CNNs and it would likely resort to classifying with smaller scale features, if there are apparent differences.

While the project seeks to entangle factors that could affect what the CNN learns, the evaluation with conflict sets does not directly review how features are processed and learned within the network. Approaches such as visualizing the activation of each neuron or layer can be more affective in this and can reveal more about how to alter the network’s sensitivity to the global features.