Graph Transformers

A study of Transformers' understanding of fundamental graph problems, where we propose a new, tailored architecture highlighting the model's potential in graph-related tasks.

Motivation & Project outline

Our project aims to advance the understanding of Transformers in graph theory, focusing on the Shortest Path Problem, a cornerstone of graph theory and Dynamic Programming (DP). We introduce a custom Graph Transformer architecture, designed to tackle this specific challenge. Our work begins with a theoretical demonstration that the shortest path problem is Probably Approximately Correct (PAC)-learnable by our Graph Transformer. We then empirically test its performance, comparing it against simpler models like Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) and sophisticated benchmarks like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). This study seeks to validate the Graph Transformer as an effective tool for solving fundamental graph-based problems, and “simple” DP problems in particular.

Introduction & Literature review

Transformers have shown significant effectiveness in domains that require an understanding of long-range dependencies and contextual information. Originally prominent in natural language processing

A particular area of interest within these applications is graph problems. Recent research has assessed Transformers’ performance in this domain

We will demonstrate that, by adapting the Transformer architecture for our purposes, the shortest path problem and other “simple” dynamic programming (DP) challenges are Probably Approximately Correct (PAC)-learnable by the model. Our approach is based on the framework developed for GNNs

Graph Transformer Model Design

Let’s dive into our Graph Transformer model, drawing inspiration from the classical Transformer architecture.

Vanilla Transformer

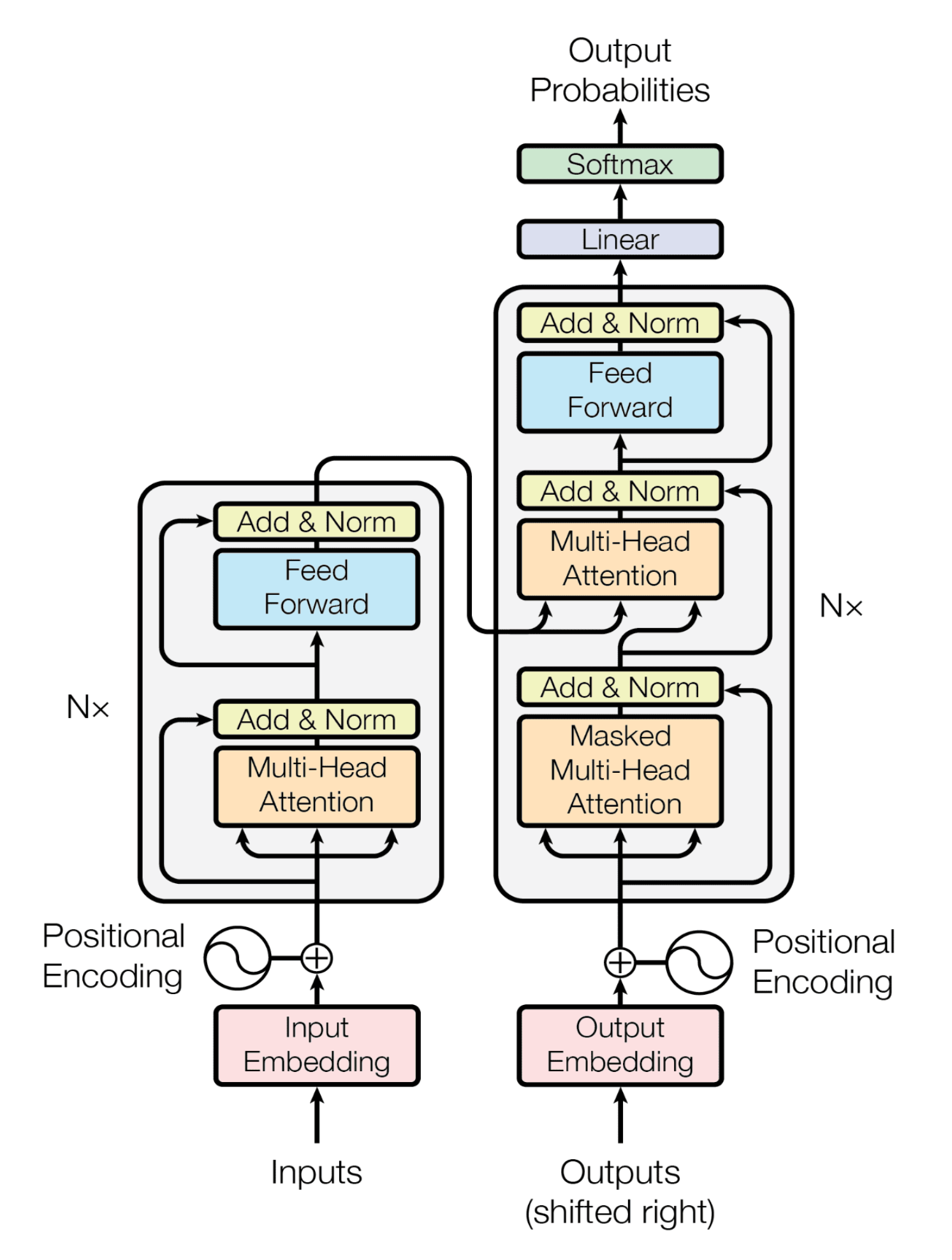

We first recall the vanilla architecture of Transformers, described in

In our context, think of tokens like the attributes of nodes in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). These tokens are packets of information, allowing transformers to handle diverse data types, including graphs. The process begins with a token net, which is a sequence of linear and non-linear layers. This is somewhat equivalent to the alternating aggregation and combination stages in a GNN, where each node processes and integrates information from its neighbors.

The real game-changer in transformers, however, is the attention mechanism, layered on top of the token net. This mechanism involves a set of matrices known as query, key, and value. These matrices enable tokens to use information from the nodes they’re paying attention to, in order to learn and update their own values.

Here’s a simple way to visualize it. Imagine each token in the transformer scanning the entire graph and deciding which nodes (or other tokens) to focus on. This process is driven by the query-key-value matrices. Each token creates a ‘query’, which is then matched against ‘keys’ from other tokens. The better the match, the more attention the token pays to the ‘value’ of that other token. Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

\[Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax \left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right)V\]In this formula, $ Q $, $ K $, and $ V $ represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively. The term $ \sqrt{d_k} $ is a scaling factor based on the dimensionality of the keys.

While the process in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) might seem similar, there’s an essential distinction to be made. In GNNs, the flow of information is local, with nodes exchanging information with their immediate neighbors. However, in our Graph Transformer model, we employ self-attention to potentially allow each node (or token) to consider information from the entire graph. This includes nodes that might be several steps away in the graph structure.

One axe of our research is then to explore the potential benefits - or drawbacks - of this global perspective, and seeing how leveraging global information compares to the traditional local feature aggregation used in GNNs, in the context of graph theory challenges like the Shortest Path Problem. By enabling each node to have a broader view of the entire graph, we’re exploring how this approach influences the prediction quality (Accuracy) and the efficiency of path computations, specifically focusing on the speed at which the network adapts and learns (Training Efficiency).

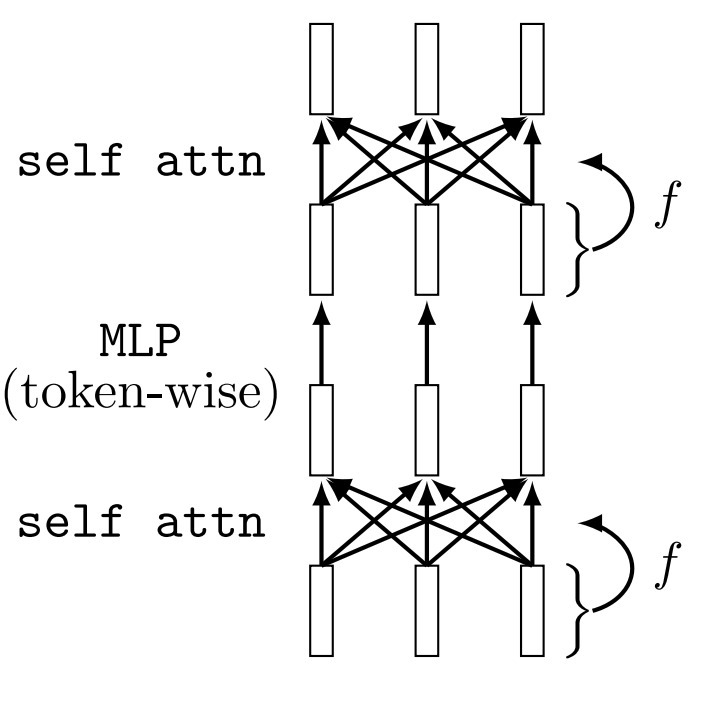

A full Transformer will be a sequence of self-attention layers and MLPs. We now turn to the specifics of how we implement it, starting with tokenization.

Tokenization Approach and Positional Encoding

The first step in our model is converting graph information (including nodes, edges, and their weights) into a format suitable for transformers. We’ve developed a method to encode this graph data into tokens.

Each token in our system is a vector with a length of $2n$. Here, $n$ represents the number of nodes in the graph. Half of this vector contains binary values indicating whether a connection exists to other nodes (1 for a connection, 0 for no connection). The other half of the vector holds the weights of these edges.

\[\text{Token} = [\text{Edge Connections (Binary Values)}, \text{Edge Weights}] = [\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{w}]\]This structure seems sufficient to capture the essential structure of the graph. But, to further aid the transformer in identifying the shortest path, we can introduce additional local information into these tokens through positional encoding. Encoding positional information of the nodes has already be achieved in various ways, for example, using graph kernels

We plan to rigorously test both approaches as part of our diverse model lineup.

Attention in Graph Transformers - the Necessity of a Skip-Connection

The Query-Key-Value (QKV) Attention Mechanism is a pivotal aspect of how Graph Transformers can effectively learn the Shortest Path Problem. Building on the insights from Dudzik et al.

Recall the Bellman-Ford algorithm’s key update step for the Shortest Path Problem, expressed as:

\[d_i^{k+1} = \min_j d_j^k + w_{i, j}\]In this context, our hypothesis is that Transformers could replicate this dynamic through the attention mechanism, which we prove mathematically in Appendix A. The key observation is that the softmax layer would be able to mimic the $ \min $ operator, as long as the query-key cross product is able to retrieve $d_j + w_{i,j}$ for all nodes $i,j$. Intuitively, this can be done if each query token $i$ picks up on the node’s positional encoding, and each key token $j$ on the node’s current shortest path value $d_j$ and edges values $w_j$. Taking the cross product of the onehot encoding $i$ with edges values $w_j$ would then return exactly $w_{i,j}$ for all $i,j$. To select only seighboring connections, we’ll use an appropriated attention mask.

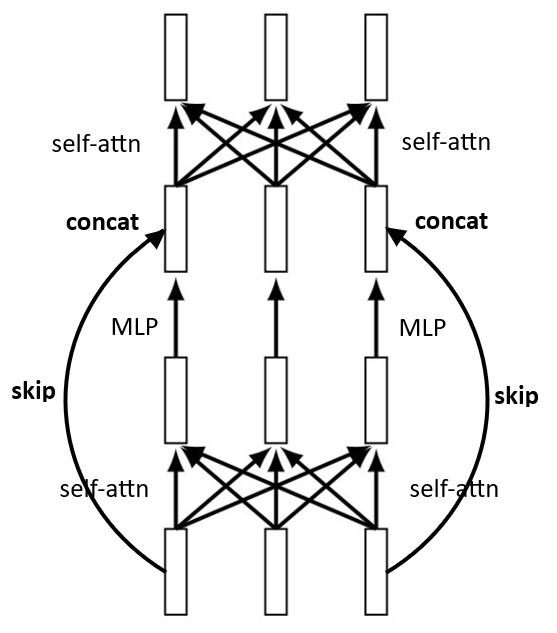

However, there is a catch. The learning process might not fully grasp the Bellman-Ford update using the attention mechanism alone. After the attention picks up on the correct minimizer neighbour token $j$, it needs to update the the current node $i$’s values. The Bellman-Ford update isn’t a simple operation on the tokens like a sum. For instance, we only want $d_i^k$ to change, and we want to update it with the correct $w_{i,j}$. This is where the idea of incorporating a skip-connection mechanism comes into play. By concatenating tokens $i$ (the input) and $j$ (the attention’s output) before feeding them to the MLP layer following the self-attention layer, we could effectively emulate the Bellman-Ford update process.

Overall, combining attention and skip-connection could ensure our Graph Transformer can comprehensively learn and apply the Bellman-Ford logic to solve the Shortest Path Problem. We offer a mathematical proof of this concept in Appendix A, using a slightly different tokenization method.

Additionally, it’s worth considering that our Graph Transformer might be learning an entirely distinct logical process for solving the Shortest Path Problem. Still, proving that such a logic is within the model’s grasp underlines the model’s versatility in addressing some graph-related and/or dynamic programming challenges. We’ll tackle this notion in the next part about learnability and algorithmic alignment.

Model Architecture Overview

In this section, we revisit the architecture of our Graph Transformer, which is an adaptation of the standard Transformer model. Our model is composed of a sequence of self-attention layers and MLPs, each augmented with a skip-connection. The tokens in our model encapsulate both edge connections and their corresponding weights, alongside positional encoding.

The most notable feature of our architecture is the introduction of the attention mask. This mask restricts the attention of each token to its immediate neighbors, aligning our approach more closely with the local message-passing process typical in GNNs. The inclusion or not of this feature and the resultant effect in our architecture marks the crucial difference between the global vs. local token aggregation methodologies that we discussed earlier.

A measure of learnability

Our project falls into the wider research interest in the interaction between network structures and specific tasks. While basic and common structures such as MLPs are known to be universal approximators, their effectiveness varies based on the amount of data required for accurate approximations. Notably, their out-of-sample performance often lags behind task-specific architectures, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in graph-related problems, which highlights the issue of a network’s generalization capacity.

To evaluate theoretically the ability of transformers to effectively learn the Shortest Path Problem and similar challenges, we position our study within the framework of PAC (Probably Approximately Correct) Learning. This framework allows us to explore the concept of algorithmic alignment. Algorithmic alignment is here crucial as it pertains to a model’s capability to emulate a given algorithm with a minimal number of modules, each of relatively low complexity. Such approach has already been taken by Xu et. al

Algorithmic Alignment

In this section, we delve into a series of definitions to establish the mathematical groundwork of our investigation.

We first recall a definition of the PAC-Learnibility:

Definition (PAC learning and sample complexity)

Let \(\{x_i,y_i\}_{i=1}^M\) be i.i.d. samples from some distribution $ \mathcal{D} $, and suppose $ y_i = g(x_i) $ for some underlying function $ g $. Let \(f = \mathcal{A}(\{x_i, y_i\}_{i=1}^M)\) be the function generated by a learning algorithm $ \mathcal{A} $. Then $ g $ is $ (M, \epsilon, \delta) $-learnable with $ \mathcal{A} $ if

\[\mathbb{P}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}} [\| f(x) - g(x) \| \leq \epsilon] \geq 1 - \delta\]where $ \epsilon > 0 $ is the error parameter and $ \delta \in (0, 1) $ the failure probability.

We then define the sample complexity as \(\mathcal{C_A}(g, \epsilon, \delta) = \min M\) for every $ M $ such that $ g $ is $ (M, \epsilon, \delta) $-learnable with $ \mathcal{A} $.

This is a crucial concept in computational learning theory that helps us understand the feasibility of learning a given function from a set of examples to a certain degree of approximation, with a certain level of confidence.

Next, we outline a definition that connects the concepts of function generation with the architecture of neural networks.

Definition (Generation)

Let $ f_1, \ldots, f_n $ be module functions, $ g $ a reasoning function and $ \mathcal{N} $ a neural network. We say that $ f_1, \ldots, f_n $ generate $ g $ for $ \mathcal{N} $, and we write \(f_1, \ldots, f_n \underset{\mathcal{N}}{\equiv} g\) if, by replacing $ \mathcal{N}_i $ with $ f_i $, the network $ \mathcal{N} $ simulates $ g $.

Using these ideas, we then introduce a key point for our project: algorithmic alignment, which we intend to validate for Transformers applied to the Shortest Path Problem.

Definition (Algorithmic alignment)

Consider a neural network $ \mathcal{N} $ with $ n $ modules \(\mathcal{N}_i\) that tries to approximate a reasoning function $ g $. Suppose that there exists $ f_1, \ldots, f_n $ some module functions such that \(f_1, \ldots, f_n \underset{\mathcal{N}}{\equiv} g\). Then $ \mathcal{N} $ is $ (M, \epsilon, \delta) $-algorithmically aligned with $ g $ there are learning algorithms \(\mathcal{A}_i\) for the \(\mathcal{N}_i\)’s such that \(n \cdot \max_i \mathcal{C}_{\mathcal{A}_i} (f_i, \epsilon, \delta) \leq M\).

A small number of sample $ M $ would then imply good algorithmic alignment, i.e. that the algorithmic steps $f_i$ to simulate g are easy to learn.

Finally, we state the following theorem, proven by Xu et al.

Theorem 1 (Algorithmic alignment improves sample complexity)

Fix $\varepsilon$ and $\delta$. Suppose ${x_i, y_i} \sim D$, where $|x_i| < N$, and $y_i = g(S_i)$ for some $g$. Suppose $\mathcal{N}_1, \dots \mathcal{N}_n$ are $\mathcal{N}$’s MLP modules in sequential order. Suppose $\mathcal{N}$ and $g$ algorithmically align via functions $f_1, …, f_n$, as well as the following assumptions.

i. Algorithm stability. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be the learning algorithm for the \(\mathcal{N}_i\)’s. Suppose \(f = \mathcal{A}(\{x_i, y_i\}^M_{i=1})\), \(\hat{f} = \mathcal{A}(\{\hat{x}_i, y_i\}^M_{i=1})\). For any x, \(\|f(x) - f(\hat{x})\| < L_0 \cdot \max_i\|x_i - \hat{x}_i\|\), for some \(L_0\).

ii. Sequential learning. We train the \(\mathcal{N}_i\)’s sequentially. The inputs for $\mathcal{N}_j$ are the outputs from the previous modules \(\mathcal{N}_1, \dots, \mathcal{N}_{j-1}\), while labels are generated by the correct functions \(f_{1}, ..., f_{j-1}\).

iii. Lipschitzness. The learned functions $f_j$ satisfy \(\|f_j(x) - f_j(z)\| \leq L_1\|x - z\|\), for some $L_1$.

Then g is learnable by N.

Application to Transformers

We now apply this theoretical framework to Transformers. The justifications of the results in this part will be a combination of sketch of mathematical proofs and empirical evidence. We first state a first result:

Lemma 1 (Transformers algorithmically align with the Shortest Path Problem)

Let $ \mathcal{T} $ be a Transformer, let $ g $ be the reasoning function of the Shortest Path Problem applied to a graph with $n$ nodes. Then $ \mathcal{T} $ is algorithmically aligned with $ g $.

We can directly prove this lemma. Let $ f_1, \ldots, f_n $ be the Bellman-Ford update processes of the Shortest Path Problem: \(d_u^{k+1} = \min_{v \in \mathcal{N}(u)} d_v^{k} + c(u, v)\) where $\mathcal{N}(u)$ is the set of neighbors of node $u$. From Bellman-Ford algorithm, we have: \(f_1, \ldots, f_n \underset{\mathcal{T}}{\equiv} g\), with $g$ being the shortest path function.

Then, from our discussion on Transformers attention layers and proof in Appendix A, each attention-MLP sequence $\mathcal{N}_i$ has a learning algorithm $\mathcal{A}_i$ such that $f_i$ is learnable with $\mathcal{A}_i$. Each sample complexity is then bounded by M, which concludes the proof.

We can now state the following theorem:

Theorem 2 (Transformers can learn the Shortest Path Problem)

Let $ \mathcal{T} $ be a Transformer, let $ g $ be the shortest path function. Then, $g$ is learnable by $\mathcal{T}$.

We provide here a sketch of a proof of this theorem. From Lemma 1, $\mathcal{T}$ and $g$ algorithmically align via $f_1, \ldots, f_n$. We must now check the 3 assumptions of Theorem 1.

Sequential Learning (ii) is clearly true, since transformers architectures incorporate sequence of MLPs (associated with attention layers). Li et al

We can then apply Theorem 1 and conclude the proof.

Having laid the theoretical foundation for our problem, we now turn our attention to the practical application, where we employ our Graph Transformer to the concrete task of learning and solving the Shortest Path Problem.

Methodology for Training and Evaluation

Constructing the Dataset

For training and evaluating our different models, we generate a comprehensive dataset comprising 50,000 samples, each representing a graph. These graphs were randomly created following the Erdős–Rényi model, specifically the $\mathcal{G}(n, p)$ variant, where n represents the number of nodes and p is the probability of edge formation between any two nodes. In our dataset, each graph consists of 10 nodes (n = 10), and the edge probability (p) is set at 0.5. This setting ensures a balanced mix of sparsely and densely connected graphs, providing a robust testing ground for the Graph Transformer’s ability to discern and compute shortest paths under varied connectivity scenarios .

Furthermore, we assign to the edges in these graphs some weights that are integral values ranging from 1 to 10. This range of weights introduces a second layer of complexity to the shortest path calculations, as the Graph Transformer must now navigate not only the structure of the graph but also weigh the cost-benefit of traversing various paths based on these weights. The inclusion of weighted edges makes the dataset more representative of real-world graph problems, where edges often have varying degrees of traversal difficulty or cost associated with them.

This dataset is designed to challenge and evaluate the Graph Transformer’s capability in accurately determining the shortest path in diverse graph structures under different weight conditions. The small number of nodes ensures a wide variability in the degree of connectivity in a sample graph. It also allows for an initial performance evaluation on smaller-scale problems, with the potential to extend these studies to larger-scale graphs in the future. Hence, the dataset’s structure supports a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance and its adaptability to a wide range of graph-related scenarios.

Training Protocols

In the fixed dataset approach we’ve employed, the dataset is pre-constructed with 50,000 graph samples and remains unchanged throughout the training process. This method, involving a consistent 60/20/20 split for training, validation, and testing, ensures that every model is assessed under the same conditions at each epoch. This consistency is crucial for our primary goal: to compare the performance of different models or architectures in a controlled and repeatable manner. To an on-the-fly approach, where data is dynamically generated during each training epoch, introduces more variability. This variability can be beneficial in a second step for thoroughly testing the robustness and adaptability of a single model, as it faces new and diverse scenarios in each epoch. However, for our first objective of directly comparing different models, the fixed dataset approach provides a more stable and reliable framework to begin with.

We use the Adam Optimizer because it’s good at handling different kinds of data and works efficiently. The learning rate is set at a standard value of 0.001, which serves as a common and reliable starting point, ensuring a consistent basis for comparing the learning performance across all models.

Our main tool for measuring success is the L1 loss function. This function is suited for our shortest path problem because it treats all mistakes the same, whether they’re big or small. It’s different from the L2 loss, which is harsher on bigger mistakes. This way, our model pays equal attention to finding shorter and longer paths correctly.

Metrics and Evaluation Criteria

We use two main metrics to check how good our models perform: L1 Loss and Accuracy. L1 Loss adds up all the differences between the predicted and actual path costs across all nodes. It’s a direct way to see how well the model is doing.

\[L1 \, Loss = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} |y_i - \hat{y}_i|\]where $ N $ is the total number of nodes, $ y_i $ is the actual path cost for the $i$-th node, and $ \hat{y}_i $ is the predicted path cost for the $i$-th node.

Accuracy is the second measure. It shows what percentage of nodes the model got exactly right in predicting the shortest path. It’s a simple way to understand how precise our model is.

\[Accuracy = \frac{\text{Number of Correct Predictions}}{\text{Total Number of Predictions}} \times 100\%\]Here, a prediction is counted as “correct” if its rounded value is the true shortest path. I.e., if the model predicts 10.3 for a node, but the true sortest path is 11, this is marked as incorrect. If it predicts 10.7, it will be counted as correct.

Together, these two measures help us see how well our Graph Transformer is doing compared to other models like MLPs and GNNs, especially in solving shortest path problems in graphs.

Results and Comparative Analysis

In our analysis, we compared the performances of MLPs, Transformers, and GNNs using our generated dataset. Initially, we evaluated the performance of each architecture across different sizes by recording in-sample and out-of-sample losses at each epoch, along with out-of-sample accuracy. We compared three model sizes: “small,” “mid,” and “large,” which correspond to the depth of the model. For GNNs, this signifies the number of iterations; for Transformers and MLPs, it refers to the number of layers. Small models have 2 iterations/layers, mid models 5, and large models 10.

To maintain fair comparisons, the MLP and the Transformer were designed to have an equal total number of trainable parameters at each size. We excluded GNNs from this comparison, as they outperformed both models with significantly fewer parameters.

GNN performance

Our GNNs demonstrated exceptional performance on the shortest path task. Tailoring the model’s architecture to this problem (using maximum aggregation and initializing node features appropriately) likely contributed to this success. However, several interesting observations emerged from our results. We compared GNNs of three different sizes: small (2 iterations, 13k parameters), medium (5 iterations, 32k parameters), and large (10 iterations, 64k parameters).

We observed that both medium and large GNNs achieved over 99% out-of-sample accuracy after just a few epochs. The large model’s performance aligns with expectations, as it conducts 10 iterations in total—matching the maximum number of iterations required by standard shortest-path-finding algorithms like Bellman-Ford for n-node graphs.

Surprisingly, the medium-sized model, with only 5 iterations, also achieved similar accuracy. This initially seems counterintuitive since 5 iterations suggest that information can only propagate to nodes within 5 neighbors. However, as noted in

This explains why the medium GNN can converge efficiently, but the small model with just 2 iterations cannot. Even with an optimized Bellman-Ford algorithm, a 2-iteration GNN would only correctly solve paths shorter than or equal to 5 nodes, limiting its overall learning capacity.

MLP performance

Although GNNs quickly converged to near-perfect predictions, their inherent suitability for the shortest path task was expected. To gauge the Transformers’ performance more accurately, we compared them with MLPs, which are not specifically designed for this task. As indicated in

The smaller MLP models converged faster, yet both small and medium models barely exceeded 50% accuracy, even after extensive training (16 epochs for GNNs and 64 for MLPs). This supports the hypothesis that MLPs face challenges in learning iterative algorithms.

Increasing model size or training duration did not significantly improve performance; the largest model struggled particularly with fitting the problem. While more hyperparameter tuning might enhance the “large” model’s performance, the “medium” model’s struggles suggest that MLPs have inherent difficulties with this task, regardless of parameter count.

Transformer performance

Turning our attention to Transformers, we initially doubted their ability to match GNN performance levels. However, the question remained: could they outperform MLPs, and if yes by how much? We began by testing a basic Transformer version (no attention mask, positional encoding, or skip connection). To ensure fair comparisons, all model sizes maintained approximately the same number of parameters as the MLPs, with equivalent layers/iterations (small: 2 layers, 44k parameters; medium: 5 layers, 86k parameters; large: 10 layers, 172k parameters).

A notable improvement in accuracy was observed, with the best-performing Transformer model reaching 70% accuracy. The training was stopped at 64 epochs to maintain consistency across all models. As it does not show signs of overfitting, extending training beyond 64 epochs might further enhance the Transformer’s performance. Interestingly, increasing the model size to over 150k parameters did not significantly boost performance under our hyperparameter settings. The small and medium architectures exhibited similar performance, with the medium model slightly outperforming after a few epochs.

Regarding sizes, similarly to the MLP, increasing the depth and parameter count of the transformer over 150k parameters doesn’t seem to help with the model’s performance, at least with our set of hyperparameters (as this big of a transformer is long to train, we haven’t been able to do much hyperparameter tuning). The small and medium architectures seem almost tied, but the medium one seems to perform better after a few epochs.

Our hypothesis in Part 1 suggested that Transformers, capable of performing $O(n^2)$ operations per attention head, should learn loop structures more effectively. However, their learning is constrained by the specific operations allowed in the attention mechanism. To test this, we proposed three enhancements to our Transformer: an attention mask, positional encoding, and a skip connection, as outlined in Part 1 and Appendix A. We hypothesized that these additions would enable the Transformer to better learn the Bellman-Ford iteration step.

Transformer with Attention Mask, Positional Encoding & Skip Connection

As discussed in Part 1, we adapted our Transformer model to include these three components, expecting an improvement in performance. The attention mask, a fundamental feature of Transformers, enables the model to focus on specific token relationships. In our setup, each token (node) attends only to its neighbors, as dictated by the adjacency matrix. We incorporated the attention mask into the medium-sized Transformer for comparison.

Next, we added positional encoding. Based on our Part 1 discussion, positional encodings can inform the feedforward network (FFN) about the neighboring tokens selected by the attention layer. We used basic one-hot encodings, effectively adding an $n×n$ identity matrix or concatenating an $n×1$ one-hot vector to each token. Although more sophisticated encodings might be beneficial, we demonstrated the feasibility of using one-hot encodings for the Bellman-Ford update.

Finally, we implemented a custom skip connection. Instead of a standard sum skip connection, our model concatenates the input and output of the attention head before feeding it into the FFN. This approach potentially allows the attention head to select a neighbor, with the FFN combining its token with the receiving node’s token.

We added each augmentation stepwise, building upon the previous modifications (e.g., transformer_pos_enc includes positional encoding, attention mask, and is medium-sized). Here are the results:

Each augmentation step led to clear improvements. Over 64 epochs, our base model’s out-of-sample accuracy improved from 70% to over 90%. The positional encoding contributed the most significant enhancement, which was somewhat surprising given its simplicity. Overall, these results support our hypothesis regarding the Transformer’s capacity to learn the Bellman-Ford iteration step.

Conclusion

In this project, we compared MLPs, Transformers, and GNNs in solving graph-related problems, with a focus on the shortest path in Erdos-Renyi graphs. Our findings indicate GNNs excel in such tasks due to their specialized architecture. However, the adaptability of Transformers, particularly with architectural modifications like attention masks, positional encodings, and skip connections, is a significant discovery. While these models showed promise, larger MLP and Transformer models faced convergence issues, highlighting the need for better hyperparameter optimization in future work.

Transformers’ theoretical success in approximating the Bellman-Ford algorithm, verified by empirical results, suggests potential in a subset of dynamic programming (DP) problems where DP updates are simple and manageable by attention heads. However, their capability is inherently limited compared to the theoretically more versatile GNNs, due to the softmax and linear combination constraints in attention mechanisms. Future work could delve into designing Transformer models with enhanced attention mechanisms, potentially broadening their applicability in complex DP problems. Investigating the synergy between Transformers and GNNs could also lead to innovative hybrid models.

Overall, our exploration sheds light on the potential of Transformers in graph-related tasks, suggesting they could offer valuable insights and solutions, alongside the more established GNNs. This finding could open up interesting possibilities for research and innovation in neural network applications, particularly in solving complex graph-related challenges.

Appendix

Appendix A.

We present here a mathematical proof of how the Graph Transformer Architecture can learn the Bellman-Ford update in the Shortest Path Problem.

We consider a slightly different tokenization: for every node $i$, at layer $k$, we encode its information in a tensor of the form:

where $\mathbb{1}_i \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is the positional encoding, $w_i \in \mathbb{R}^n$ the edges weights and $d_i^k$ the current shortest distance computed at layer $k$.

Recall the formula of query-key-value attention:

\[t_i = \frac{\sum_{j} \exp^{-q_i' k_j / \sqrt{2n+1}}v_j}{\sum_{j} \exp^{-q_i' k_j / \sqrt{2n+1}}}\]Set up the weights matrices as:

\[\begin{cases} W_Q = \begin{pmatrix} I_{n+1} & O_{n \times n+1} \\ 1_n & 0_{n+1} \end{pmatrix}\\ W_K = \begin{pmatrix} O_{n+1 \times n} & I_{n+1} \end{pmatrix}\\ W_V = I_{2n+1} \end{cases}\]so that \(q_i' k_j = w_{j,i} + d_j\) i.e. attention is determined by the update values of the Bellman-Ford equation.

Hence taking the softmax - and if necessary augmenting the weights of the matrices by a common factor -, we have the ouput \(t_{j^\star}\) for the appropriate node \(j^\star = \text{argmin}_j \{w_{j,i} + d_j\}\).

Notice that in this configuration \(t_{j^\star}\) is not enough to retrieve the desired edge weight \(w_{i, j^\star}\) : we need the positional encoding from node $i$.

The skip-connection achieves this, by concatenating original input $t_i$ with attention output \(t_{j^\star}\). We can then retrieve the desired value \(w_{j^\star,i} + d_{j^\star}\) with the MLP of layer $k$, which concludes the proof