Graph Articulated Objects

Pre-trained large vision-language models (VLMs), such as GPT4-Vision, uniquely encode relationships and contextual information learned about the world through copious amounts of real-world text and image information. Within the context of robotics, the recent explosion of advancements in deep learning have enabled innovation on all fronts when solving the problem of generalized embodied intelligence. Teaching a robot to perform any real-world task requires it to perceive its environment accurately, plan the steps to execute the task at hand, and accurately control the robot to perform the given task. This project explores the use of vision-language models to generate domain descriptions. These can be used for task planning, closing the gap between raw images and semantic understanding of interactions possible within an environment.

Project Background

Recent advancements in generative AI have transformed robotic capabilities across all parts of the stack, whether in control, planning, or perception. As self-driving cars roll out to public roads and factory assembly-line robots become more and more generalizable, embodied intelligence is transforming the way that humans interact with each other and automate their daily tasks.

Across the robotic manipulation stack, we are most interested in exploring the problem of scene representation; using the limited sensors available, how might a robot build a representation of its environment that will allow it to perform a wide range of general tasks with ease? While developments in inverse graphics like NeRF have given robots access to increasingly rich geometric representations, recent work in language modeling has allowed robots to leverage more semantic scene understanding to plan for tasks.

Introduction to Task Planning

In robotics, the term task planning is used to describe the process of using scene understanding to break a goal down into a sequence of individual actions. This is in contrast with motion planning, which describes the problem of breaking a desired movement into individual configurations that satisfy some constraints (such as collision constraints). While simply using motion planning to specify a task is necessary for any generalized robotic system, task planning provides robots with a high-level abstraction that enables them to accomplish multi-step tasks.

Take the problem of brushing one’s teeth in the morning. As humans, we might describe the steps necessary as follows:

- Walk to the sink.

- Grab the toothbrush and toothpaste tube.

- Open the toothpaste tube.

- Squeeze toothpaste onto brush.

- Brush teeth.

- Rinse mouth.

- Clean toothbrush.

- Put everything back.

Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) Explained

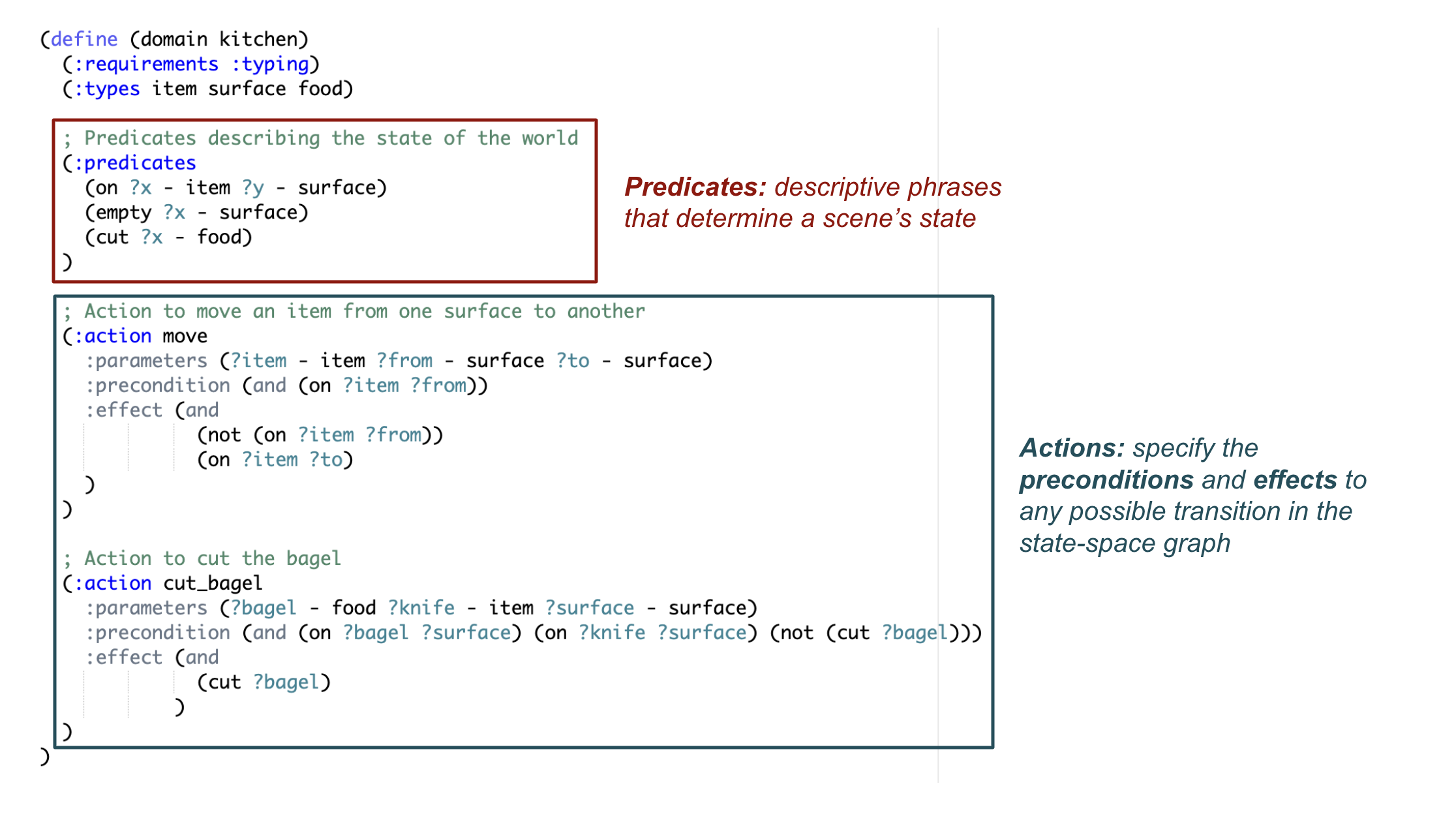

Creating a task plan is a trivial task for humans. However, a computer must use a state-space search algorithm like A* search to plan a sequence of interactions from a start state to a desired goal state. Doing so requires us to define a standard that formally specifies all relevant environment states, along with the preconditions and effects of all possible transitions between two states.

The Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) was invented to solve this problem. Description languages like PDDL allow us to define the space of all possible environment states using the states of all entities that make up the environment. Environments are defined as a task-agnostic domain file, while the problem file defines a specific task by specifying a desired start and end state.

Despite task planning’s utility, however, there is one major drawback; this approach to planning requires the robot to have a detailed PDDL domain file that accurately represents its environment. Generating this file from perception requires not only a semantic understanding of all objects in a space, but also of all possible interactions between these objects, as well as all interactions that the robot is afforded within the environment. Clearly, there is a major gap between the task-planning literature and the realities of upstream perception capabilities.

Related Work

The use of LLMs in robotic planning and reasoning has exploded in the past few years, due to the promise of leveraging a language model’s internal world understanding to provide more information for planning. One such work is LLM+P

LLMs have also been used to solve plans directly, to varying levels of success. Works like SayCan

Language is an increasingly promising modality for robots to operate in, due to the ubiquity of relevant language data to learn real-world entity relations from the internet. However, foundation models that integrate vision and robot-action modalities enable even stronger semantic reasoning. Google’s Robot Transformer 2 (RT-2)

Nonetheless, multi-modal foundation models have proven to be a useful tool across the spectrum of robotic planning. Our project takes inspiration from the above works in LLMs for planning and extends the idea to domain-generation, allowing task-planners to work in real-world scenarios.

The rapid advancement of LLMs and vision-language models open up a world of possibilities in closing this gap, as robotic perception systems may be able to leverage learned world understanding to generate PDDL files of their own to use in downstream planning tasks. This project aims to investigate the question: can VLMs be used to generate accurate PDDL domains?

Experimental Setup

To investigate this, we decided to explore this problem by testing the capabilities of VLMs on various tasks and levels of prior conditioning. This allows us to explore the problem on two axes: domain complexity and amount of information provided as a prior to the VLM. Each of these axes are chosen to progressively increase the complexity of the domain being explored, while also progressively increasing the amount of information available. Designing our experiments like this allows us to understand the importance of information and domain complexity and how they affect the overall results.

Due to ease of access, we decided to use OpenAI ChatGPT’s GPT4-Vision functionality to run our experiments. A more comprehensive ablation may analyze these experiments across a wider range of VLMs.

Domains of Interest

Within the context of task planning for generalizable robotics, the problem of cooking in a kitchen setting is a fascinating problem because of the combination of their usefulness and the high dimensionality and discretization of kitchen tasks. As a result, kitchen setups like cooking, cleaning, and cutting ingredients are great ways to understand task-planning, and are the domains that we chose to study in this work.

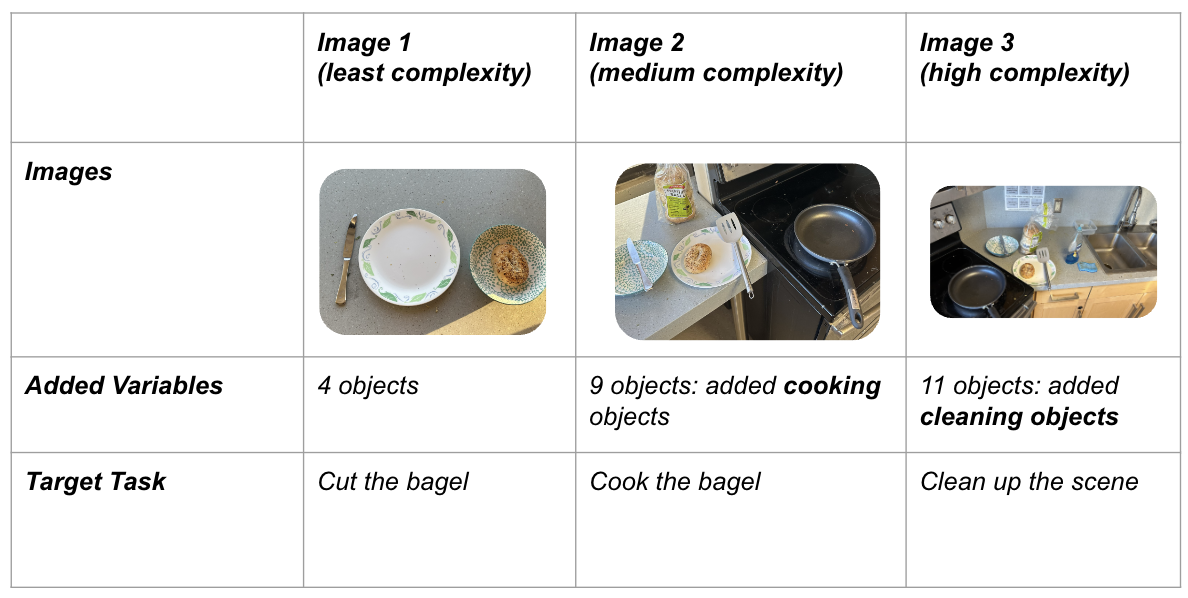

The three domains used in our study are:

- Cut: Bagel + utensils used for cutting ingredients

- Cook: Everything in Cut + a pan, spatula, and a stove

- Clean: Everything in Clean + a soap bottle, a sink, and a sponge

Our handcrafted “ground-truth” domain files are designed to support the target tasks of cutting a bagel, cooking a sliced bagel, and cleaning utensils, respectively. Ideally a good PDDL file generated is one where these tasks are supported.

Prompting Strategies.

We also experimented with four different prompting strategies, with each strategy providing progressively more information to the VLM for its PDDL generation task. All prompts provided to the VLM consist of the target image, along with a text-based prompt meant to guide the VLM towards a more accurate PDDL representation.

The strategies are as follows, along with examples used by our experiment for the cut domain. Text that was added progressively to the prompt is bolded:

- Raw Generation: Image + generic prompt

- You are a robot that needs to execute task planning in the setup shown in the image. Given the image, please generate a Planning Description Domain Language (PDDL) domain file that describes the scene.

- Prompt 1 + describe each object in the scene

- You are a robot that needs to execute task planning in the setup shown in the image. This image includes a bagel, a plate, a bowl, and a knife. Given the image, please generate a Planning Description Domain Language (PDDL) domain file that describes the scene.

- Prompt 2 + describe the target task

- You are a robot that needs to execute task planning to cut the bagel in the setup shown in the image. This image includes a bagel, a plate, a bowl, and a knife. Given the image, please generate a Planning Description Domain Language (PDDL) domain file that describes the scene.

- Prompt 3 + explain object relations in detail

- You are a robot that needs to execute task planning to cut the bagel in the setup shown in the image. This image includes a bagel, a plate, a bowl, and a knife. In order to cut the bagel, one must use the knife and place the bagel and knife on the plate beforehand. I can place the bagel on the plate or the bowl, and cut the bagel using the knife. Given the image, please generate a Planning Description Domain Language (PDDL) domain file that describes the scene.

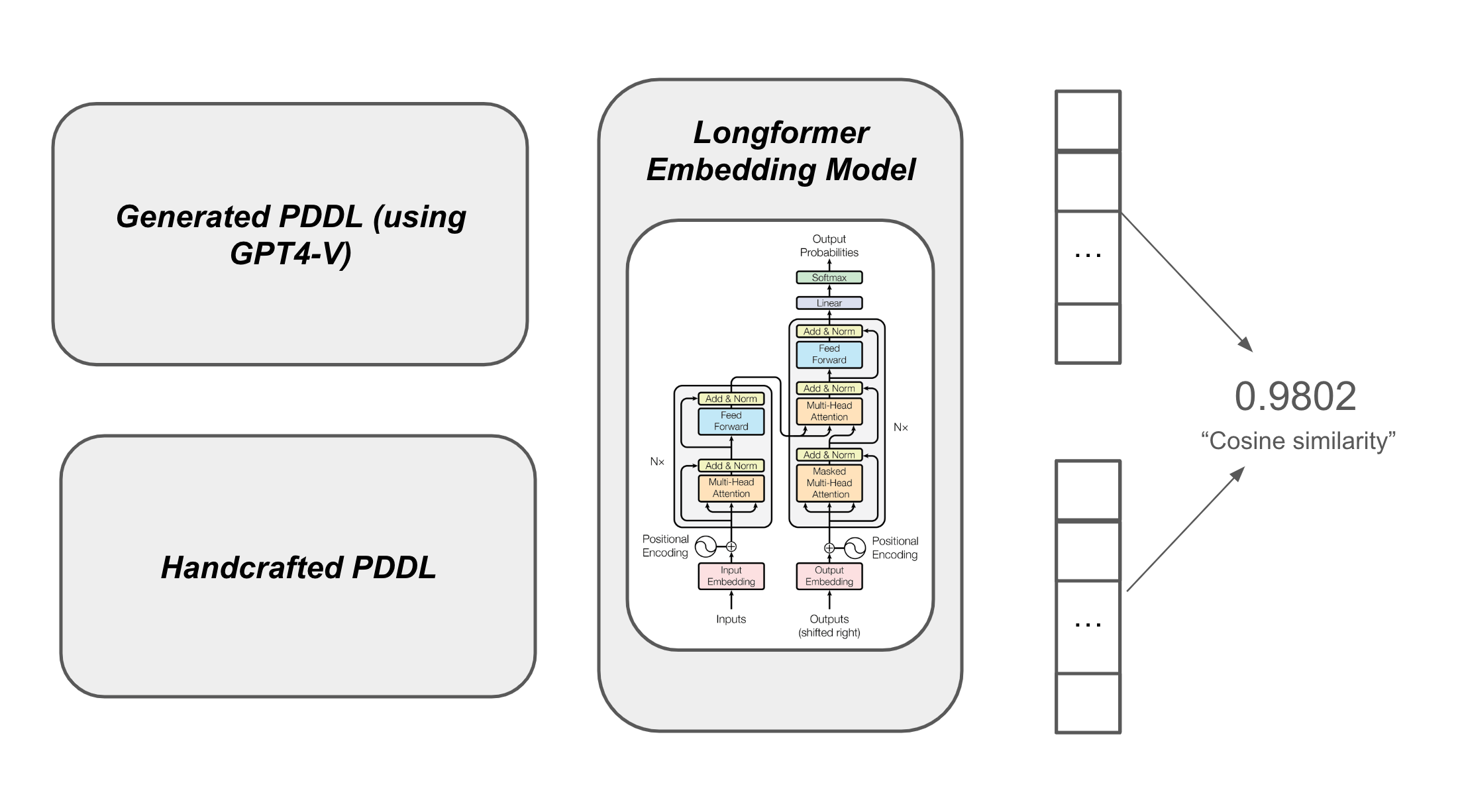

Evaluation Metric: Embedding Cosine Similarity

Since several different PDDL domains can be used to represent the same set of actions and predicates, the task of generating PDDL files is quite subjective. Since generating PDDL tasks is an often-tedious task that humans must do themselves to represent any given domain, we evaluate each VLM output based on its similarity to real PDDL domains handcrafted manually. After asking the VLM to generate a PDDL file, both the target and the generated domain descriptions are embedded using the Longformer: Long Document Transformer

Note that this cosine similarity in the embedding space is quite a coarse metric to evaluate our outputs for a couple of reasons. The primary concern with this evaluation approach has to do with the transferability between PDDL files, which are specified in a LISP-like syntax, and natural language documents, which Longformer was trained to embed. In this study, we assume that such an embedding model can be used to make such a comparison, and discuss our study accordingly.

Aside from this, PDDL’s structure also provides several keywords that are commonly used by all PDDL files, such as action, predicate, and preconditions. In order to handle these, we decided to simply remove all instances of these words from both the target and the generated PDDL files, in order to mitigate the effect of the similarity between these tokens.

Results

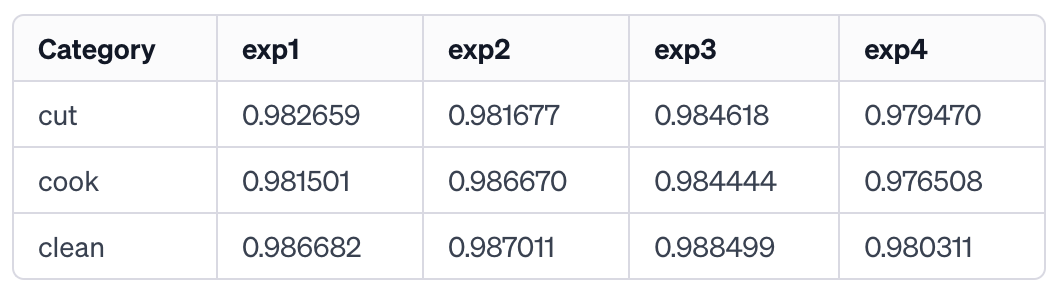

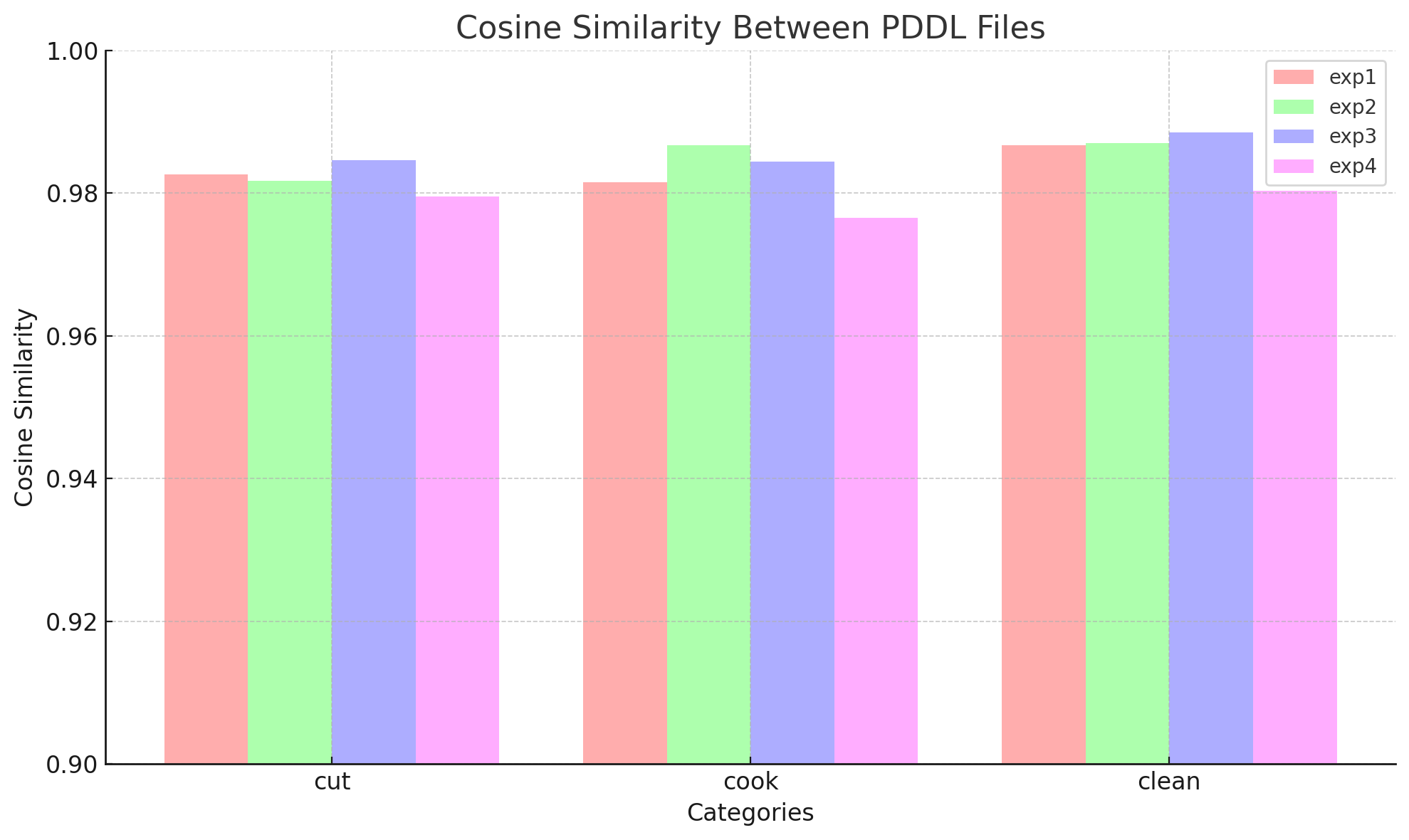

After experimenting on a wide range of complex environments with various prompting strategies, it seems that VLMs perform quite well for the task of generating PDDLs from image and text conditioning. We measured the similarity of the ground truth PDDL file with each image and experiment’s generated PDDL file. To quantitatively measure similarity, we used the cosine similarity metric on the embeddings of the masked pieces of text using Longformer

The exact generated PDDL files can be found at this link

First, we will qualitatively analyze the generated words in each of the three categories of the PDDL files: types, predicates, and actions. Then, we will also provide quantitative metrics that measure similarity directly with the ground truth PDDL files that we wrote.

Types

Types are the first part of PDDL files. They describe the various sorts of objects that appear in the image. For example, in the “cut” image, the generated types are “utensil, plate, food”. Note that the types often compress similar sorts of objects, e.g. both spatulas and knives fall under the type “utensil”. Type generation is somewhat inconsistent, since types are not strictly required by PDDL files to exist, which could contribute towards why certain generated PDDL files do not have a types section at all.

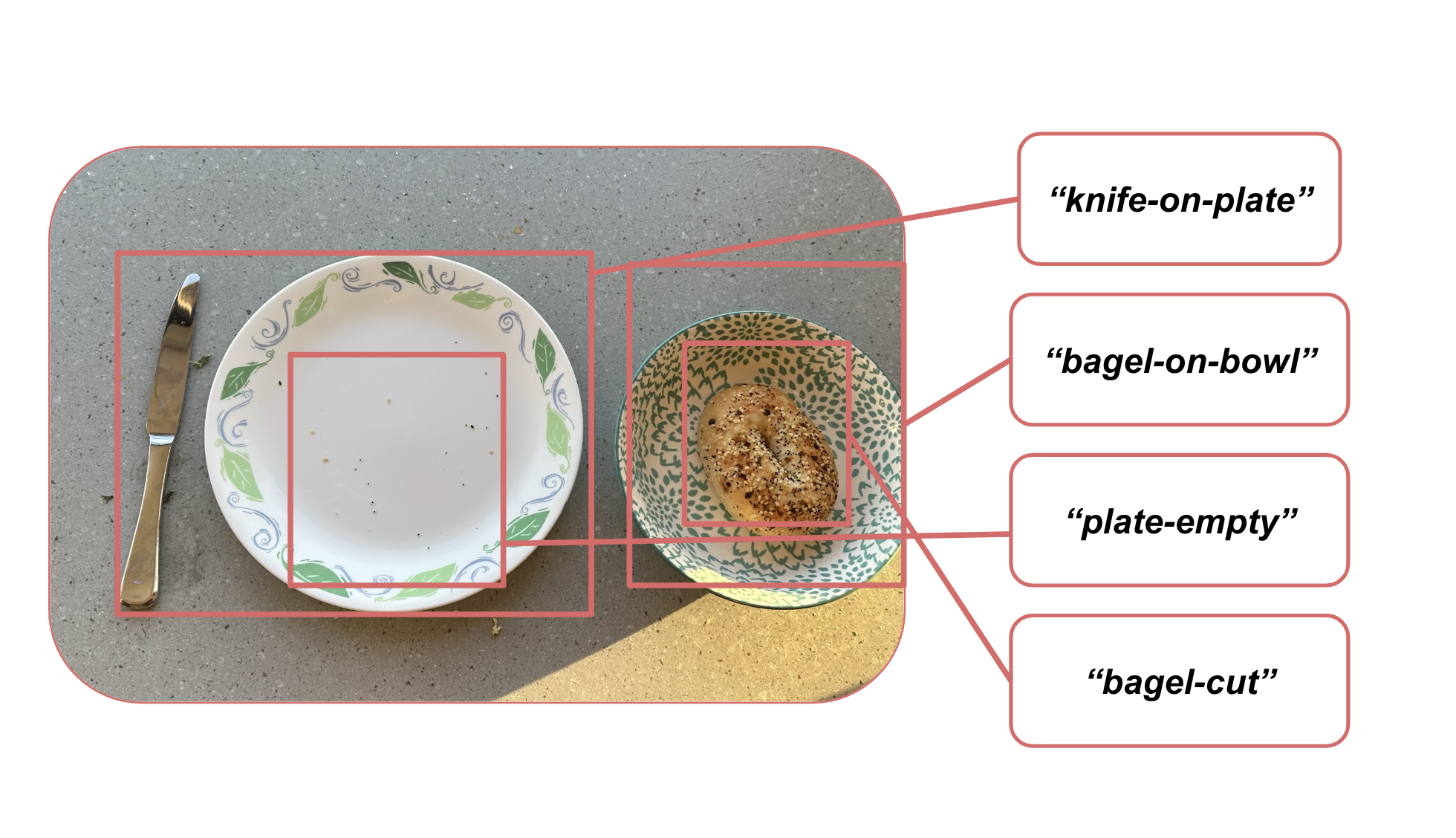

Predicates

Predicates in the PDDL files are descriptive phrases that describe distinct parts of the scene, at a given time. For example, in the “cut” image, experiment 4 has the following predicates “(plate-empty), (bowl-empty), (bagel-on-plate), (bagel-on-bowl), (knife-on-plate), (bagel-cut)”. Note that these are not precisely representative of the current state of the image, but rather represent what states could also appear in the future, e.g. “(bagel-cut)”, even though the bagel is not yet cut. The accuracy of the generated predicate set is surprisingly accurate, regardless of which experiment we use.

It seems that all four experiments generate approximately the same predicate set. For the “cut” image, all of the predicates generally have the objects “bagel”, “knife”, “plate”, etc., and sometimes where they are placed relative to each other. In the later “cook” and “clean” images, there are also predicates conditioning on whether the bowl/plate is clean or not. In particular, the generated predicates for Experiment 1 – where we do not tell the VLM the task – also make sense with respect to the inferred task! This evidence suggests that the generated predicates match the planned task, thus implying that the VLM is able to learn the task quite well just based on the image.

Actions

Similar to the predicate generation, the action generation is extremely accurate. The various sequences of predicted actions make sense for the given images and conditioning. For example, one of the generated action sequences from Experiment 1 is:

(:action prepare-sandwich :parameters (?b - food ?p - container) :precondition (and (contains ?p ?b) (is-clean ?p)) :effect (and (inside ?b ?p) (not (empty ?p))) )

This is a very detailed sequence of actions, which also makes sense – in order to prepare a sandwich, the generated PDDL file notices we need the food and the container, and then checks if it is clean and not empty.

Again, the results from Experiment 1 compared to the later experiments which have more textual conditioning are extremely similar, indicating that most of the information the VLM collects is from the image. Our added conditioning does not seem to improve generation of the action sequences much more.

Quantitative Analysis with Cosine Similarity

Along with qualitative analysis of each part of the PDDL file, we also performed a holistic analysis of the entire PDDL file that compares similarity with our handcrafted ground truth PDDL file. We measured the cosine similarity between the two PDDL files, for each experiment in each image. Due to the general format of PDDL files, certain words appear at the same places many times. Hence, we masked these words out, in order to not inflate the similarity in a superficial manner.

As we can see, our methods performed quite well, with masked cosine similarity consistently above 0.98. This makes sense qualitatively as well, since as discussed above, the VLM generated types, predicates, and actions that made sense.

One of the most noteworthy aspects of the above data is that according to this metric:

- Experiments 1-3 all perform similarly, with some doing better than others in different images.

- Experiment 4 consistently performs worse than Experiments 1-3.

This is surprising, since we would expect that more conditioning implies better performance. In Experiment 4, we added certain conditioning of the form of textual relationship between objects in the image. This result leads us to the conclusion that adding this sort of conditioning is not helpful for PDDL file generation, and is in fact negatively correlated with performance. Previous analysis has implied that the VLM learns extremely well from the image alone, and this result suggests that in fact it is better to let the VLM learn only from the image, without adding too much of our own conditioning.

Conclusion: Limitations and Future Work

Our work analyzes the potential of the recent advances in VLMs for the purposes of robotic task planning. By creating a systematic set of experiments over increasingly complex images, we were able to showcase the power of VLMs as a potentially very powerful tool for general task planning problems. The accurate generation of PDDL files based on only the images shows us that VLMs learn from images extremely well, without the need for extra textual conditioning. In fact, we noticed that providing too much conditioning actually can decrease performance, thus further suggesting that VLMs learn best from images. This result is promising for generalizing to the greater context of robotic task planning, since vision is one of the most prominent ways in which robots dynamically task plan when navigating real-world environments. Harnessing the power of VLMs could prove to be the future of robotic task planning.

There are a couple of limitations in our work, which have the potential for future exploration. In order to test the true utility of the generated domain files, we would need to also generate problem PDDL files, after which we could run the problem on the domain to test the robustness of the domain. The qualitative and quantitative metrics in our study heavily imply that our domain file is valid, by testing on ground truth PDDL files. However, a more comprehensive study could also concurrently generate problem files, which are tested on the generated domain file. Perhaps a method could be made which alternatively trains both the problem and domain files by iteratively testing the problem on the domain, similar to the idea of a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)