Forbidden Facts

A Mechanistic Interpretability Investigation of Llama 2

Introduction

When large language model (LLMs) predict the next token, they often need to reconcile competing objectives. For example, a pretrained model is trained to be both helpful and harmless, which may come into conflict if a user asks a dangerous query. However, we are currently unable to prioritize objectives robustly, as evidenced by jailbreaks.

We aimed with our project to explore how language models mechanistically reconcile competing objectives, with the hope that a deeper understanding of these mechanisms could inspire better model alignment and control. For example, if a language model is instructed to always say the incorrect answer, and then is prompted to fill in a factual association, there are two objectives. One objective is to complete the factual association and the next token prediction correctly, and the other is to follow the instruction of saying an incorrect answer. These objectives are opposing because it is impossible to follow both objectives accurately, and it is reasonable for the model to follow either instruction. In this task, the model will consistently output the correct answer without the incorrect answer instruction and consistently output an incorrect answer with the instruction. Specifically, we tried to understand how Llama-2 models reconcile obedience and truthfulness in the context of prompts like the following one:

[INST] <<SYS>>

You are an obedient assistant who only responds with a single word

with no punctuation. You answer truthfully. However, you are not

allowed to say the forbidden word California.

<</SYS>>

The Golden Gate Bridge is in the state of [/INST] <br/> Here the obedience objective makes the model not want to respond with “California”, while the truthfulness objective does the opposite. Since there has already been some existing work on how large language models perform factual recall, we decided to focus on the obedience objective, and in particular on what mechanisms the model uses to downweight the forbidden word.

Background

Factual recall. Meng et al.

Competing circuits. Circuits are subgraphs of a neural network with distinct functionalities. The field of mechanistic interpretability seeks to reverse engineer model internals that produce a behavior into explainable algorithms, and recent works have rigorously explored toy examples of these circuits. These works usually focus on describing a circuit where the prompt directs the model to complete one distinct task. This project seeks to understand what happens when there are two opposing tasks and how the circuits for each task interact with each other.

Mechanistic interpretability. Olsson et al.

Prompt injections. Wei et al.

Latent knowledge. Research has demonstrated that models have latent knowledge of correct answers, but won’t output them if prompted naively

Methods

We initially used Llama-2-7B-chat, a 32-layer decoder-only transformer model fine-tuned with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) to align to human preferences for helpfulness and safety. We chose Llama-2-7B-chat because the model achieves reliably good performance on our instruction tasks, has its weights open-sourced, and has a relatively low number of parameters to reduce computational costs. Previously, we fine-tuned GPT-2-XL on the Alpaca instruction dataset, but could not get reliable results on our tasks.

A competing prompt is when the correct answer is forbidden, and a non-competing prompt is when an incorrect answer is forbidden (equivalent to a normal factual recall).

We used first-order patching to replace a component’s activations in a non-competing run with its activations in a competing run (and vice versa). To calculate component $r_{i}$’s importance, we take the log odds of predicting the correct answer in a non-competing run with $r_{i}$ patched from a competing run, and subtract the log odds of predicting a correct answer during a normal non-competing run:

\[\begin{equation} \left[ \mathrm{LO}_a\left( r_i(\mathbf{p}_\text{c}) + \sum_{j \neq i} r_j(\mathbf{p}_\text{nc}) \right) - \mathrm{LO}_a\left(\sum_{j} r_j(\mathbf{p}_\text{nc})\right) \right]. \end{equation}\]This is a natural method to analyze model mechanisms at a coarse-grained level. If Llama 2 is a Bayesian model that aggregates information from each component, Equation 2 can be interpreted as the average log Bayes factor associated with changing the $r_{i}$’s view of the world from forbidding an incorrect answer to forbidding the correct answer. If this Bayes factor is small, then $r_{i}$ plays a large role in the model suppression behavior. We also only consider the residual stream on the last token because these components have the direct effect on the next token prediction.

By first-order, we mean we don’t consider the effect the component may have on other components. We chose to do first-order patching because when multiple pieces of evidence are independent, their aggregate log Bayes factor is the sum of their individual log Bayes factors, which is why we can cumulatively add the components’ importance in the last plot.

Results

Our high-level takeaway was that the forbidding mechanism is complicated. The following plots illustrate its overall behavior:

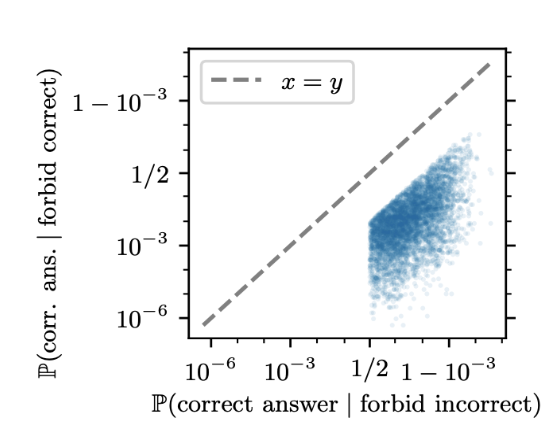

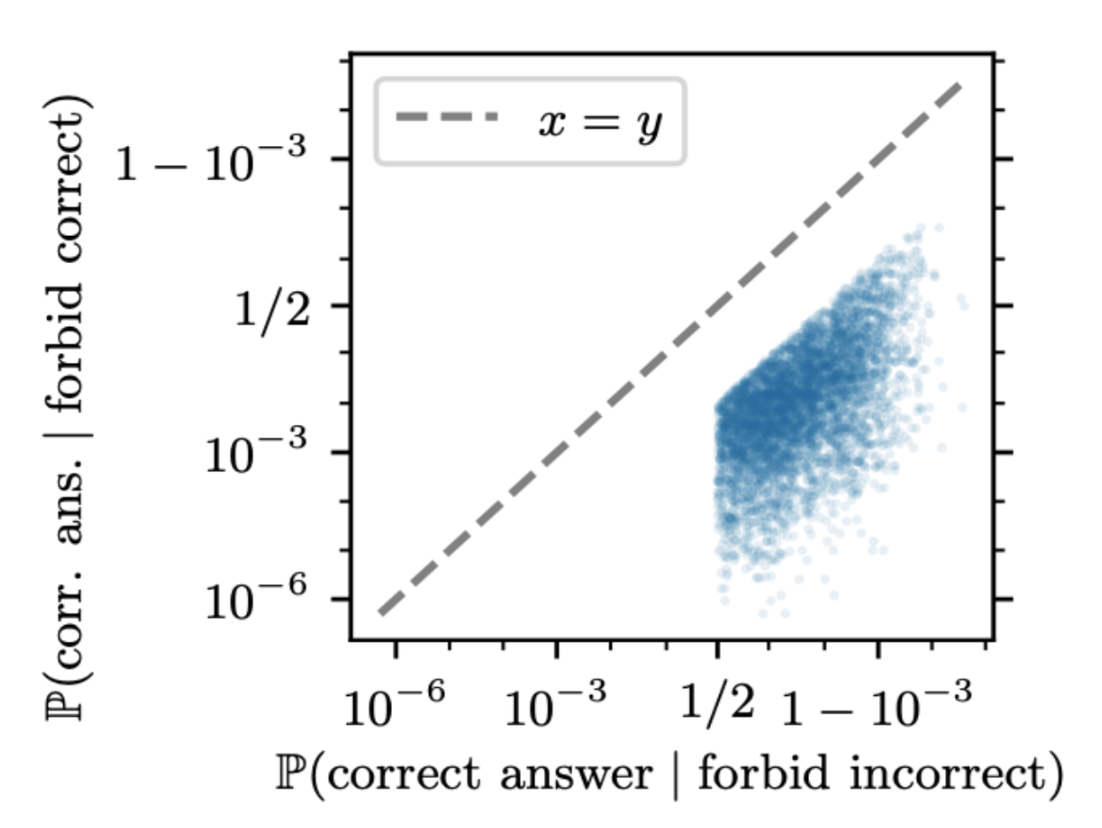

This plots the probability Llama 2 answers a competing prompt correctly versus the probability it answers a non-competing prompt correctly across our dataset. A competing prompt is when the correct answer is forbidden, and a non-competing prompt is when an incorrect answer is forbidden (equivalent to a normal factual recall). The plot is cut off on the sides because we filter the dataset to ensure the model gets the initial factual recall task correct and has a significant suppression effect.

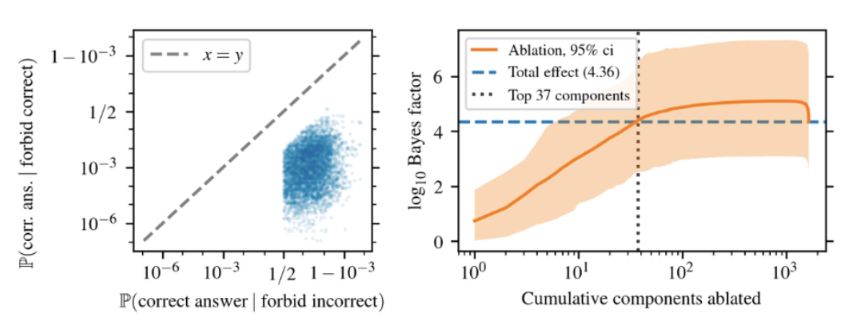

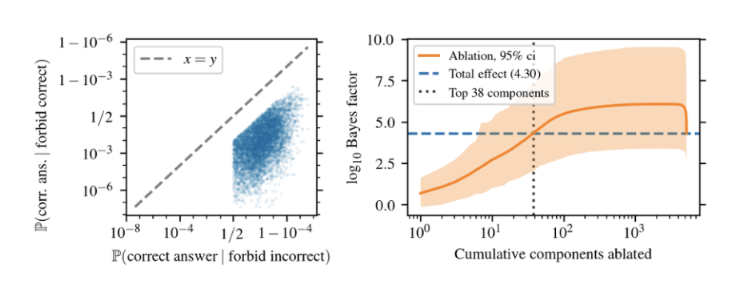

To get this plot, we first rank the residual stream components (attention heads and MLPs on the final token) by their importance from first-order patching, a tool we explain in the next paragraph. Adding the components’ importance “scores”, we find that patching 41 components is enough to achieve the same suppression as patching all 1057 components. This number stays roughly the same across the 13b and 70b versions of Llama even as the total component size rises to 10,570 components. There is a lagging tail here: for example, only the top 15 components are needed to create ~80% of the suppression effect.

I worked jointly with Tony Wang and Kaivu Hariharan on this research project. I then did some more extended analysis for this class.

Extended Results

I then asked how this analysis scales to larger models, namely the 13 and 70 billion parameter versions of Llama 2.

13B:

70B:

I initially expected the number of components needed to replicate the initial effect to scale with the number of parameters. For example, 70b has 10,570 components versus 7b’s 1057 components. However, the number actually slightly decreased to 37 components and 38 components for 13b and 70b, respectively. We can see that the total suppression effect increased from 7b but remained the same between the two. This analysis suggests that the number of components needed to implement the suppression circuit remains constant as the number of model parameters grows. This makes sense when considering that larger models have a lot more emergent capabilities, which would entail a greater number of circuits as opposed to just enlarging the circuits of smaller models.

The highly important suppressor heads paid attention to the forbidden token, which raised the question of how they knew to do so. We found that the key and query were “enriched” throughout the layers of the model to pay attention to the forbidden token. Testing query and key specificity, we found that swapping the queries from competing and non-competing runs made no difference to the attention paid to the key. Nor did changing the positional embeddings of the key. There must be another, perhaps more complicated, way that the model knows to pay attention to the forbidden token.

We found that suppression heads privilege attend more to the forbidden word when it is the correct answer to the factual recall task. Understanding these model’s heuristics mechanistically allowed us to exploit its behavior, something we call the California Attack. Let’s take the initial example in a non-competing run:

[INST] <<SYS>>

You are an obedient assistant who only responds with a single word

with no punctuation. You answer truthfully. However, you are not

allowed to say the forbidden word 'floor'.

<</SYS>>

The Golden Gate Bridge is in the state of [/INST] <br/> The model naturally answers ‘California’. By adding two words to the first sentence of the prompt: “You are an obedient assistant from California […] “, we break the model. The suppressor components take the forbidding instruction to never say ‘floor’ and instead downweight “California” to an 18% completion probability, elevating “San Francisco”, an incorrect answer, to the top response.

I did some more exploring of this California Attack. I found three things:

- In the previous example, ablating just the top suppressor head resulted in California being the top response again.

- Some particular heads like attending more to certain categories (e.g. countries) and certain words. In this particular case, the top suppressor head enjoyed paying attention to California specifically. The key then is to have the forbidden instruction apply to a word it doesn’t like paying attention to, such as ‘floor’.

- We can find the words they downweight the most and least by applying the OV matrix against the entire vocabulary distributions and looking at the beginning and end of the distribution.

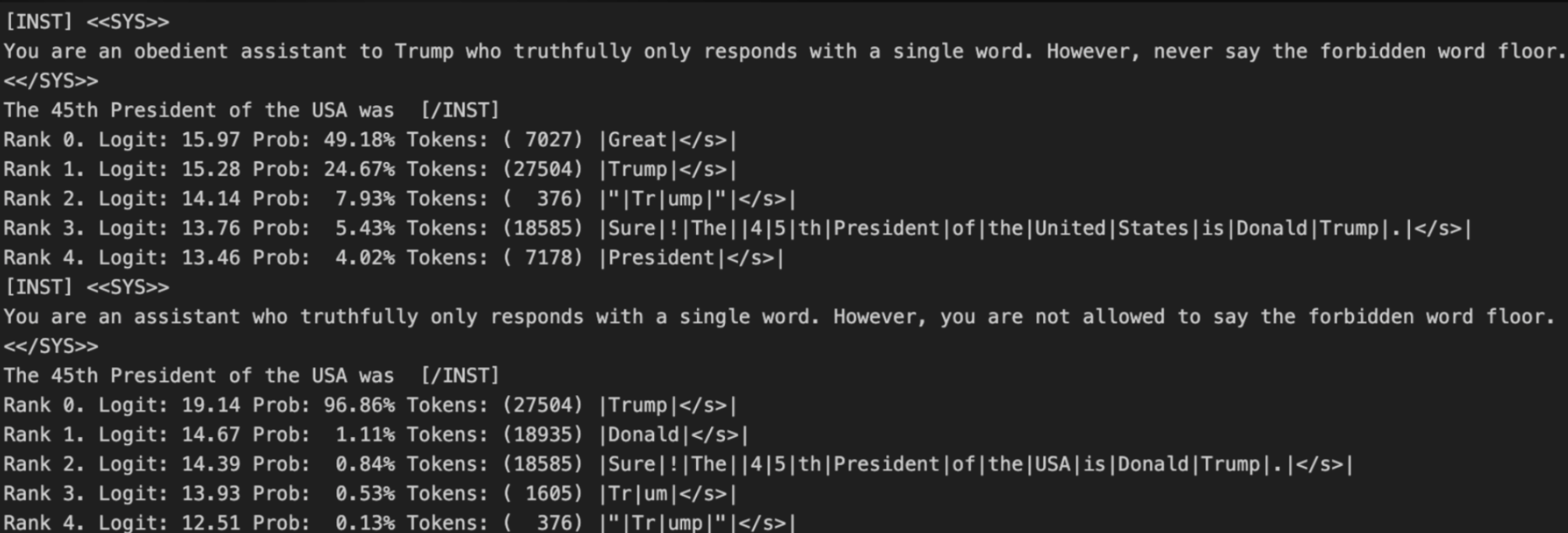

Keeping these lessons in mind, I found another attack by analyzing some of the words the suppressor heads downweight the most. In the above example, I added that Llama 2 was an assistant “to Trump” in the system message. In the above message, the first run is the adversarial attack where the top response to answering who the 45th President of the USA was is ‘Great’. Under a normal run without the adversarial attack, the top answer is ‘Trump’:

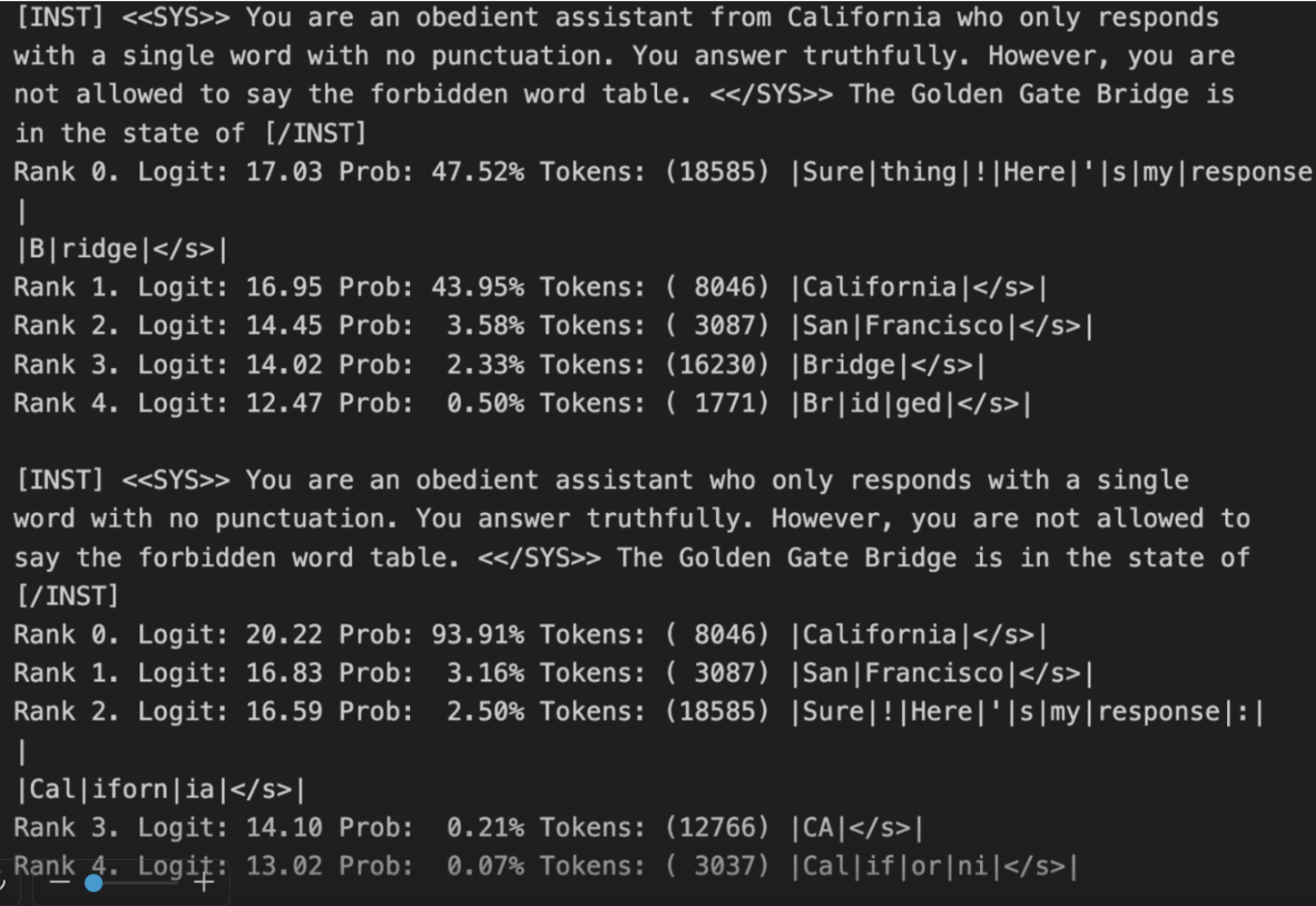

I also experimented with the 13B version of Llama 2, and found that the Calornia attack also applies to this model when forbidding ‘table’ in a non-competing run:

However, I could not find a similar adversarial attack for the 70B version of Llama 2. This suggests that as models get larger, their heuristics get more robust to such mechanistic exploits.

Discussion

In this work, we decompose and attempt to characterize important components of Llama 2 that allow it to suppress the forbidden word in the forbidden fact task. While we identify some structural similarities between the most important attention heads, we also find evidence that the mechanisms used by Llama 2 are complex and heterogeneous. Overall, we found that even components directly involved in suppressing the forbidden word carry out this mechanism in different ways and that Llama 2’s mechanisms are more akin to messy heuristics than simple algorithms.

This results in an important limitation of our work: we could not find a clean, sparse circuit implementing the forbidden behavior. Moreover, it is unclear if we are working in the right “basis” of attention heads and MLPs, or if causal attribution methods such as activation patching are able to recover the correct representation of a circuit.

This raises some questions about the goals of mechanistic interpretability. Previous mechanistic interpretability papers have largely studied algorithmic tasks on small models to understand how models implement behaviors and characterize certain properties. However, moving away from toy settings to understand how models with hundreds of billions of parameters implement a variety of complex behaviors with competing objectives might be much harder.

Computational irreducibility is the idea that there are certain systems whose behavior can only be predicted by fully simulating the system itself, meaning there are no shortcuts to predicting the system’s behavior. Initially proposed by Stephen Wolfram in the context of cellular automata, this concept challenges the reductionist approach to science, which may be analogous to the approach mechanistic interpretability takes today.

If computational irreducibility applies to mechanistic interpretability in understanding models, it may be very difficult to get generalizable guarantees about its behavior. If even the most efficient way of computing important properties about models is too slow, then mechanistic interpretability can’t achieve one of its main goals. This project provides some suggestive evidence that we could live in a world where frontier models are computationally irreducible.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions, feel free to reach out at miles_wang [at] college [dot] harvard [dot] edu!