Denoising EMG signals

The future of brain-computer interfaces rests on our ability to decode neural signals. Here we attempt to ensemble ML techniques to extract useful information from sEMG signals to improve downstream task performance.

Introduction

Brain-machine interfaces (BCIs) have the potential to revolutionize human-computer interaction by decoding neural signals for real-time control of external devices. However, the current state of BCI technology is constrained by numerous challenges that have limited widespread adoption beyond clinical settings thus far. A critical barrier remains the intrinsically high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) present in nerve recordings, which introduces substantial noise corruption that masks the relevant neural signals needed for effective device control. To address this persistent issue and work toward unlocking the full capabilities of BCIs for practical real-world application, significant advancements have been actively pursued in both hardware and software components underlying state-of-the-art systems.

Innovations on the hardware front aim to obtain higher-fidelity measurements of neural activity, providing cleaner inputs for software-based decoding algorithms. Novel sensor materials, unconventional device architectures, and integrated on-chip processing have shown promise toward this goal. For example, advancing the conformality and resolution of electrode arrays through new nanomaterials facilitates more targeted recordings with enhanced SNR by achieving closer neuron proximity and tissue integration. Novel satellite electrode configurations have also demonstrated derivations less susceptible to artifacts. While these approaches indicate positive directionality, substantial room remains for developing next-generation hardware able to circumvent the most fundamental limitations imposed by volume conduction effects that dominate nerve signal propagation physics.

Complementing these efforts, software techniques present immense potential to extract meaningful patterns straight from noisy raw recordings. The crux lies in designing sophisticated algorithms that can effectively denoise and transform complex neural data into compact, salient representations to feed downstream interpretable models. Myriad computational methods have been investigated spanning modeling, preprocessing, feature encoding, decoding, and prediction stages across model architectures. For preprocessing, techniques like low/high-pass filters, Fourier transforms, wavelet decompositions, empirical mode decompositions, and various outlier removal methods help restrict signal components to relevant frequency bands and statistics. Building upon these preprocessed signals, advanced unsupervised and self-supervised representation learning algorithms can then produce high-level abstractions as robust inputs for downstream tasks such as gesture classification. The proposed study aims to contribute uniquely to this mission by developing a novel framework tailored for preprocessing surface EMG signals. By focusing on noninvasive surface recordings, findings could generalize toward unlocking adoptable BCIs beyond strict clinical environments. Additionally, optimizing a sophisticated denoising autoencoder architecture reinforced with latest self-attention mechanisms will enrich encoded representations. Overall, this research anticipates advancing signal processing fundamentals underlying next-generation BCI systems positioned to transform human-computer interaction through widely accessible, adaptable platforms.

Literature Review

The recent debut of BrainBERT

These nascent outcomes build upon seminal prior art pioneering self-attentive neural network frameworks for combating pervasive noise corruptions. Specifically, the 2021 study “DAEMA: Denoising Autoencoder with Mask Attention”

Present work seeks to advance signal encoding breakthroughs within this mission by implementing DAEMA-inspired attention components for multi-channel surface EMG data. The overarching motivation is developing an optimized model capable of extracting robust representations from notoriously noisy recordings that sufficiently retain nuanced muscle activation details critical for control inference. By concentrating learned encodings exclusively on clean input sections, downstream analyses from subtle gesture delineation to complex modeling of coordination deficiencies may become tractable where previously obstructed by artifacts. Outcomes would carry profound implications for unlocking ubiquitous responsive assistive technologies.

Methodology

From a large sEMG dataset

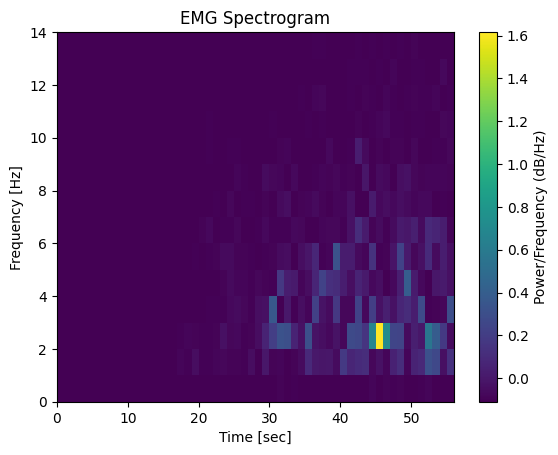

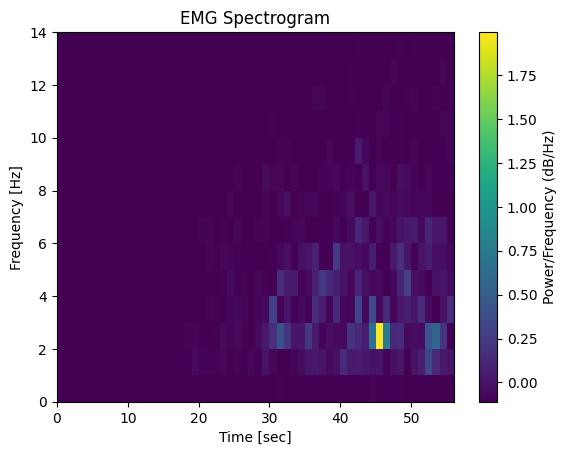

As a preprocessing step before feeding signals into my model, I first converted the 1D raw temporal traces into 2D spectrogram representations via short-time Fourier transforms. This translation from time domain to frequency domain was motivated by observations in the BrainBERT study, where the authors empirically found that presenting spectral depictions enabled superior feature extraction. To further improve conditioning, I normalized the matrix values using the global dataset mean and standard deviation.

My methodology centered on designing and training an autoencoder architecture for denoising tasks. This system was composed of an encoder model to map inputs into a lower-dimensional latent space and a partner decoder model to subsequently reconstruct the original input. Specifically, the encoder segment utilizes a multi-headed self-attention transformer layer to reweight the relative importance of input spectrogram features reflective of signal clarity versus noise. By computing dot products between each time-frequency bin, the attention heads assign higher relevance weighting to bins more strongly correlated with other clear regions of the input. In this way, the model focuses on interconnections indicative of muscle physiology rather than random artifacts. Encoder feed-forward layers subsequently compress this reweighted representation into a low-dimensional latent embedding capturing core aspects. Batch normalization and non-linearities aid training convergence. Critically, this forces the model to encode only the most essential patterns, with excess noise ideally filtered out.

The output then passes through a series of linear layers with ReLU activations to compress the data into a 28-dimensional latent representation (versus 56 originally). Paired with the encoder is an LSTM-based decoder that sequentially generates the full reconstructed spectrogram by capturing temporal dynamics in the latent encoding. Specifically, two bidirectional LSTM blocks first extract forward and backward sequential dependencies. A final linear layer then projects this decoding to match the original spectrogram shape. Since spectrograms consist strictly of positive values, the decoder output is passed through a final ReLU layer as well to enforce non-negativity.

For training, I used a custom loss function defined as a variant of mean absolute error (MAE), with additional multiplicative penalties for overestimations to strongly discourage noise injection. While mean squared error (MSE) is conventionally used for regressors, I found that it failed to properly penalize deviations in the spectrogram context as values were restricted between zero and one. Moreover, initial models tended to overshoot guesses, spectrally spreading energy across additional erroneous frequency bands - a highly undesirable artifact for signal clarity. The custom loss thus applies much harsher penalties for such over-predictions proportional to their deviation magnitude. The purpose of the loss function is to compare the model’s output to the preprocessed signal, not the original raw input. This is what makes a denoising autoencoder different from a traditional autoencoder. So, this autoencoder is being tested on its ability to reconstruct the signal from a compressed latent representation and to ignore the noise removed by manual preprocessing of the signal.

Results Analysis

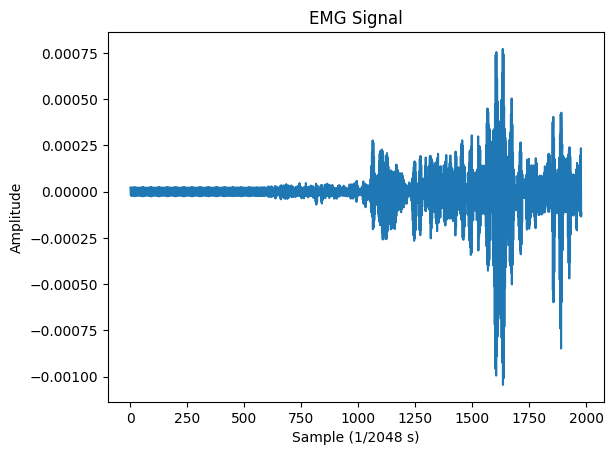

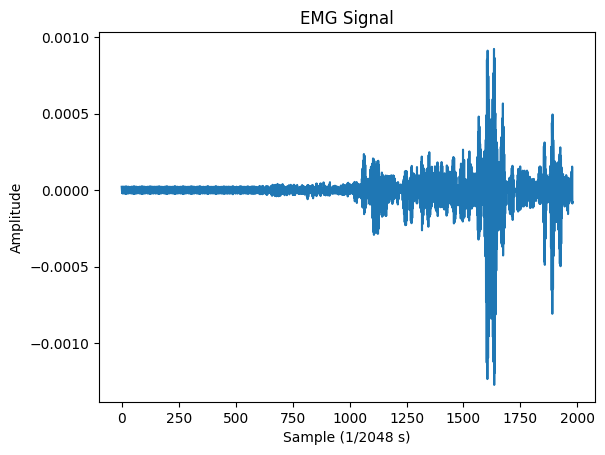

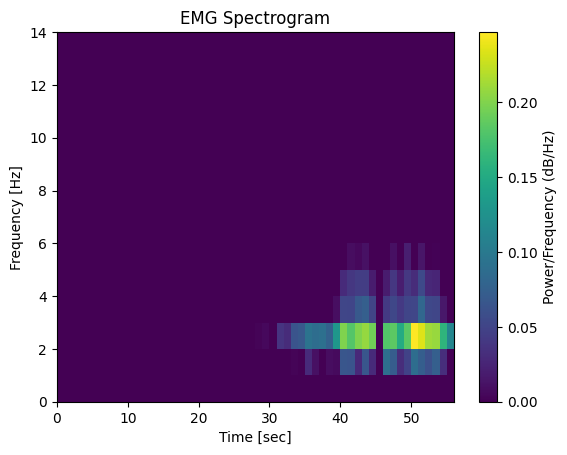

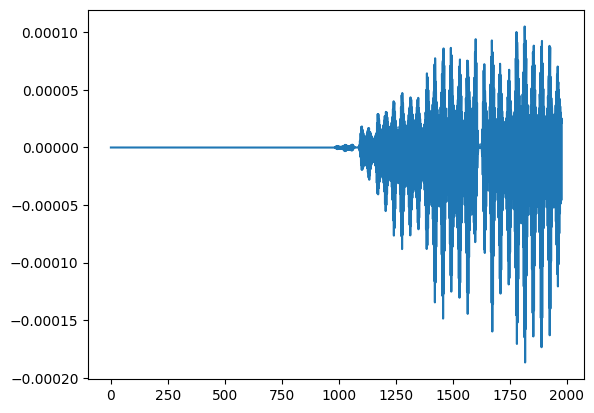

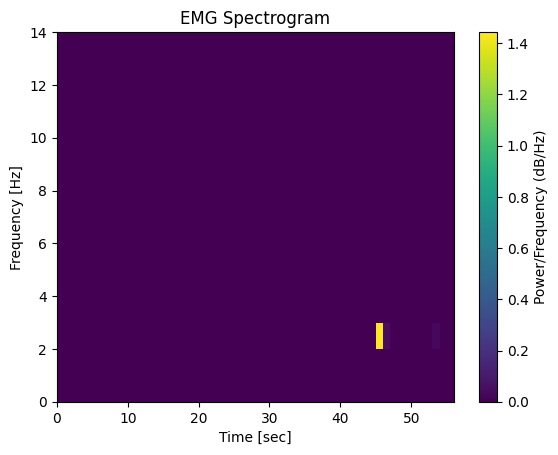

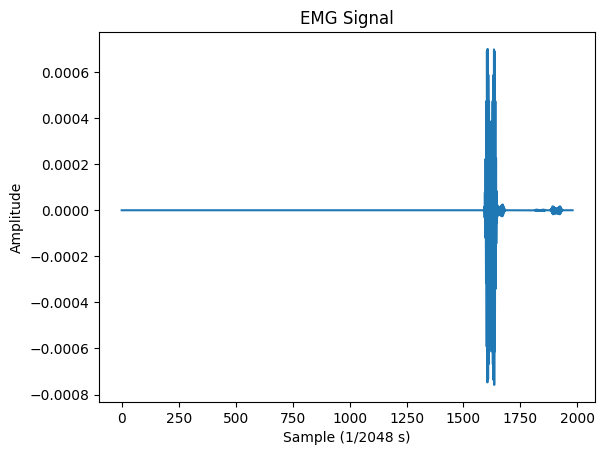

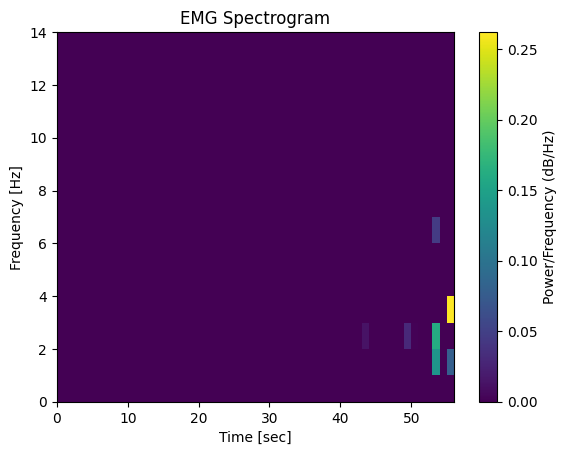

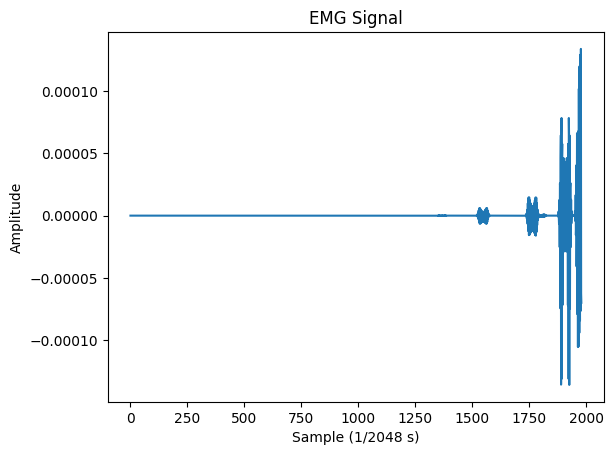

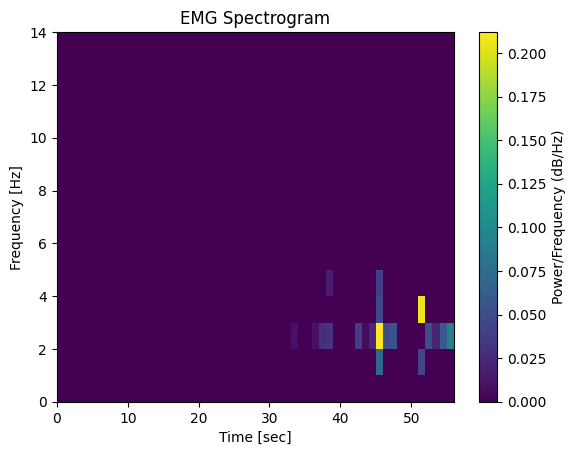

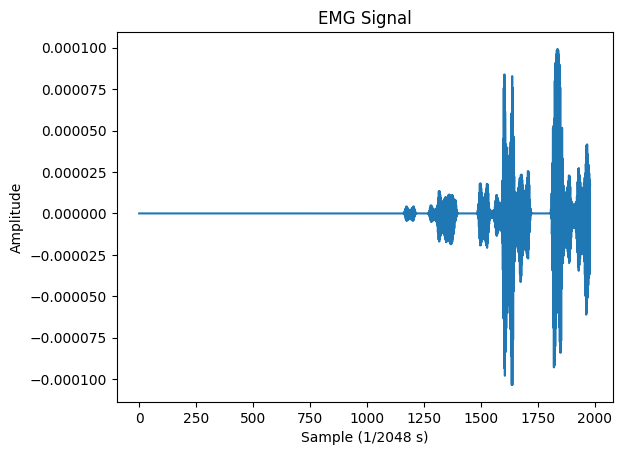

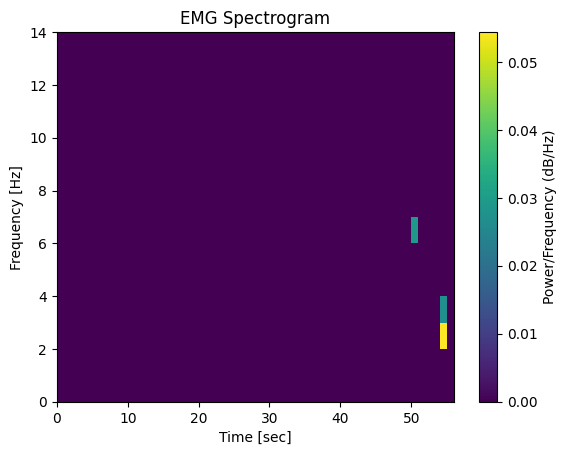

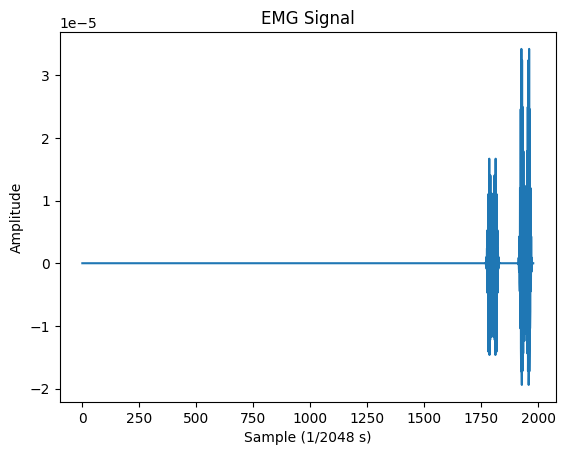

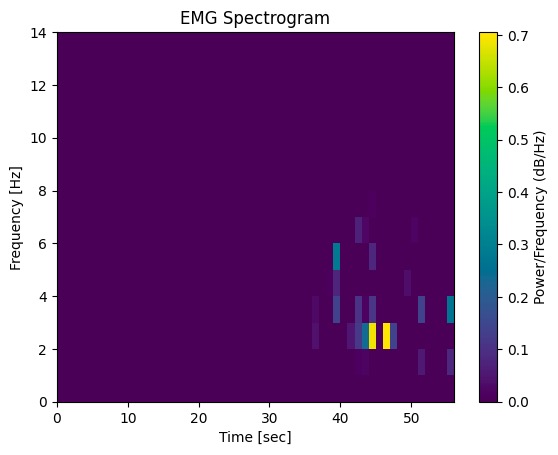

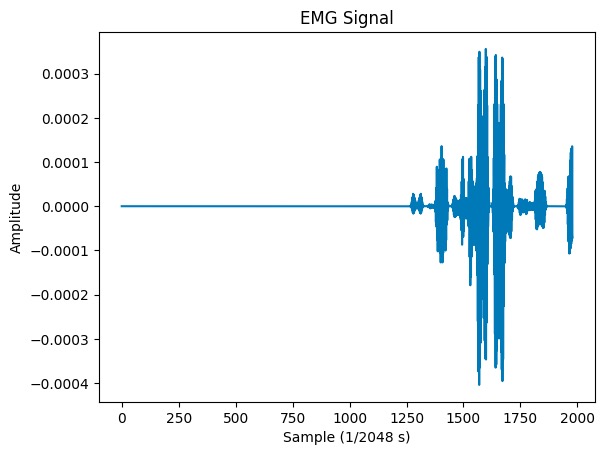

In terms of model optimization, I incrementally adapted components like attention heads, linear layers in the encoder, LSTM layers in the decoder, and loss function parameters to improve performance. Below are some results collected during experiments, with relevant hyperparameter values listed. For context, the first signal from the validation is visualized below. Note that all experiments were done on the same sample.

Loss Function

MSE loss function:

Applying MSE during training resulted in substantial overpredictions within reconstructed spectrograms. As shown, the final time-domain trace from the poorly constrained model contains heavy ambient noise contamination spanning multiple frequency bands – an undesirable artifact significantly corrupting signal clarity and interpretation. This confirms the need to explicitly restrict amplification predictions to retain fidelity.

Custom Loss at 1.5:

The custom loss variant with a penalty strength of 1.5 on positive deviations provides initial mitigations toward avoiding false noise injection. As evident for this setting however, while reconstruction quality exhibits cleaner sections, erratic artifacts still visibly persist in certain regions indicating room for improvement. Additionally, certain key activity spikes demonstrate misalignments suggestive of feature misrepresentation issues. This reconstruction is less noisy than the output when using MSE loss, but the large spike between samples 1500 and 1750 is still quite noisy.

Custom Loss at 3.0:

In contrast, a high 3.0 penalty parameter induces oversuppressions that completely smooths out nontrivial aspects of the true activations, retaining only the most prominent spike. This signifies that an over constrained optimization pressure to limit noise risks excessively diminishing important signal features. An appropriate balance remains to be found between both extremes.

Increased Depth

Additional LSTM layers:

Attempting to append supplemental LSTM decoder layers resulted in models failing to learn any meaningful representations, instead outputting blank spectrograms devoid of structure. This occurrence highlights difficulties of vanishing or exploding gradients within recurrent networks. Addressing architectural constraints should be prioritized to add representational power.

Additional Linear Layers:

Increasing the number of linear encoder layers expects to smooth outputs from repeated feature compressions, improving noise resilience at the cost of losing signal details. However, experiments found that excessive linear layers suppressed the majority of outputs indicative of optimization issues - possibly vanishing gradients that diminish propagating relevant structures.

Doubled attention heads:

Using eight attention heads over two layers was expected to extract more salient input features thanks to added representational capacities. However, counterintuitively, the resulting reconstructions surfaced only a single prominent activity spike with all other informative structure entirely smoothed out. This suggests difficulties in sufficiently balancing and coordinating the priorities of multiple simultaneous attention modules.

Latent Bottleneck

Larger latent space:

Expanding the dimensionality to a 42 dimension latent representation afforded more flexibility in encoding input dynamics. While this retained spike occurrences and positioning, relative amplitudes and relationships were still improperly reflected as evident by distorted magnitudes. This implies that simply allowing more latent capacity without additional structural guidance is insufficient for fully capturing intricate physiological details.

Smaller latent space:

As expected, severely restricting the representational bottleneck to just 14 units forced aggressive data compression that fails to retain more than the most dominant input aspects. Consequently, the decoder could only partially reconstruct the presence of two key spikes without correctly inferring amplitudes or locations. All other fine signal details were entirely lost due to the heavy dimensionality restriction forcibly imposing information loss.

Conclusion

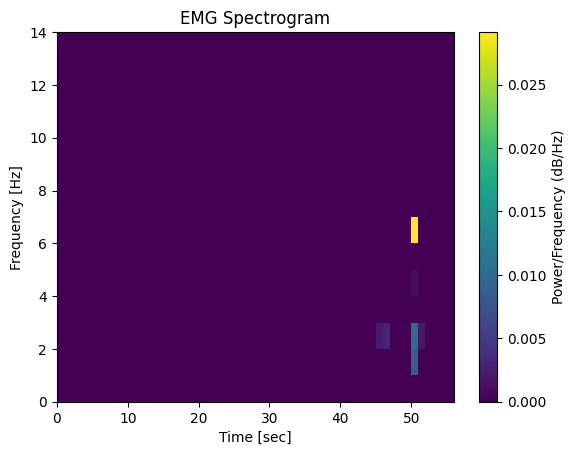

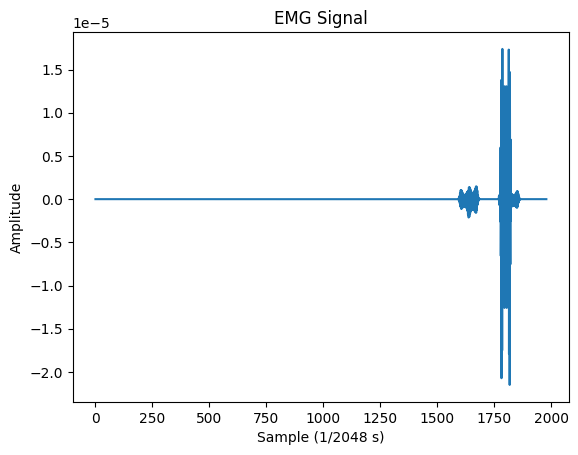

This research presents foundational outcomes qualifying the early potential of an interpretable attention-based autoencoding framework for intrinsic physiological pattern extraction and noise suppression. Incrementally adapted model configurations, guided by empirical ablation studies, demonstrate promising capabilities in capturing key EMG spectrogram characteristics while filtering errant artifacts.

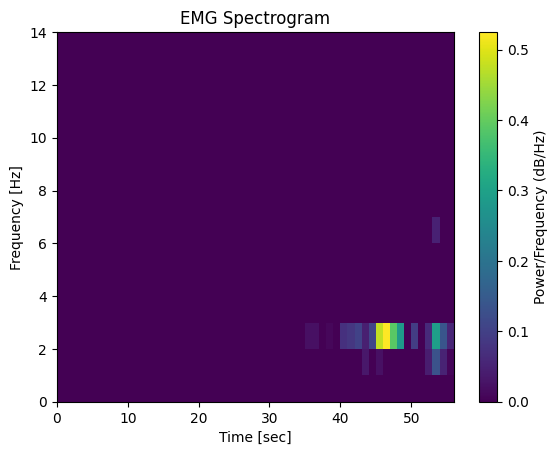

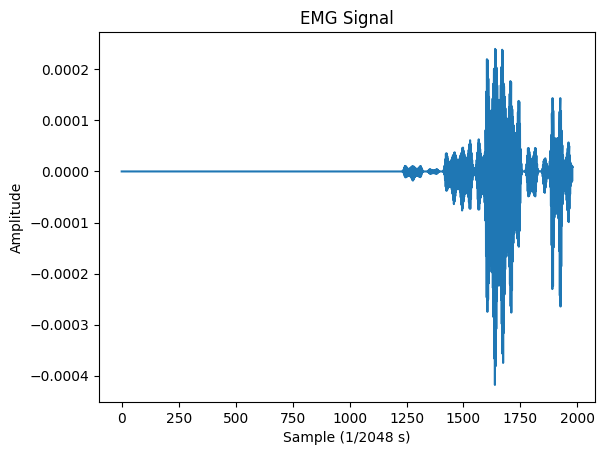

The final model parameters include: four attention heads, two attention layers, two linear layers in the encoder, 35 dimensional latent space, two LSTM layers in the decoder, and a 2.25 overshooting penalty multiplier for the custom loss function. These parameters were identified to be optimal after running the experiments described above.

Results using same experimental set-up as in previous section:

When compared to the original sample, the output of my model succeeded in reproducing the signal with most of the relevant spikes, as determined by visual inspection. Note that the error is still quite large, but I believe that is an effect of the preprocessed signals still containing quite a lot of noise, since the manual filtering is not very strong. With smaller learning rate and more training iterations, the model’s output will resemble the preprocessed signal more closely.

In addition to further testing the parameters selected above, more work could be done in selecting the values of training hyperparameters like the gradient clipping norm maximum and learning rate scheduler parameters. Both of these methods are supposed to help with gradient stability during training and are most helpful when performing training over hundreds, if not thousands, of iterations.

While this project was able to produce a denoising autoencoder model that could be used to preprocess EMG signal data, another goal was to learn a latent representation that improves performance on downstream tasks. Extending this work by reproducing results from gesture recognition papers using the latent representation of EMG data instead of the normal representation. The latent representation is expected to improve performance because the attention module is expected to highlight all of the relevant parts of the signal and the linear module is expected to use the insights from the preceding attention module to condense the signal to its latent representation. This representation is impressive at removing artifacts from the signal, which means it probably contains the information needed for downstream tasks. Previous deep learning methods

In short, the findings support the potential of attention boosted autoencoders in overcoming challenges that have hindered widespread adoption of BCI due to noise from instruments. The results highlight the importance of combining new design approaches in deep learning with specific problem-related preferences to accurately capture physiological details.