VGAE Clustering of the Fruit Fly Connectome

An exploration of how learned Variational Graph Auto-Encoder (VGAE) embeddings compare to Spectral Embeddings to determine the function of neurons in the fruit fly brain.

Motivation

Everything you’ve ever learned, every memory you have, and every behavior that defines you is stored somewhere in the neurons and synapses of your big, beautiful brain. The emerging field of connectomics seeks to build connectomes–or neuron graphs–that map the connections between all neurons in the brains of increasingly complex animals, with the goal of leveraging graph structure to gain insights into the functions of specific neurons, and eventually the behaviors that emerge from their interactions. This, as you can imagine, is quite a difficult task, but progress over the last few years has been promising.

Now, you might be asking yourself, can you really predict the functions of neurons based on their neighbors in the connectome? A paper published by Yan et al. in 2017

Although impressive, the C. elegans connectome has only ~300 neurons, compared with the ~100,000,000,000 in the human brain; however, this year (2023):

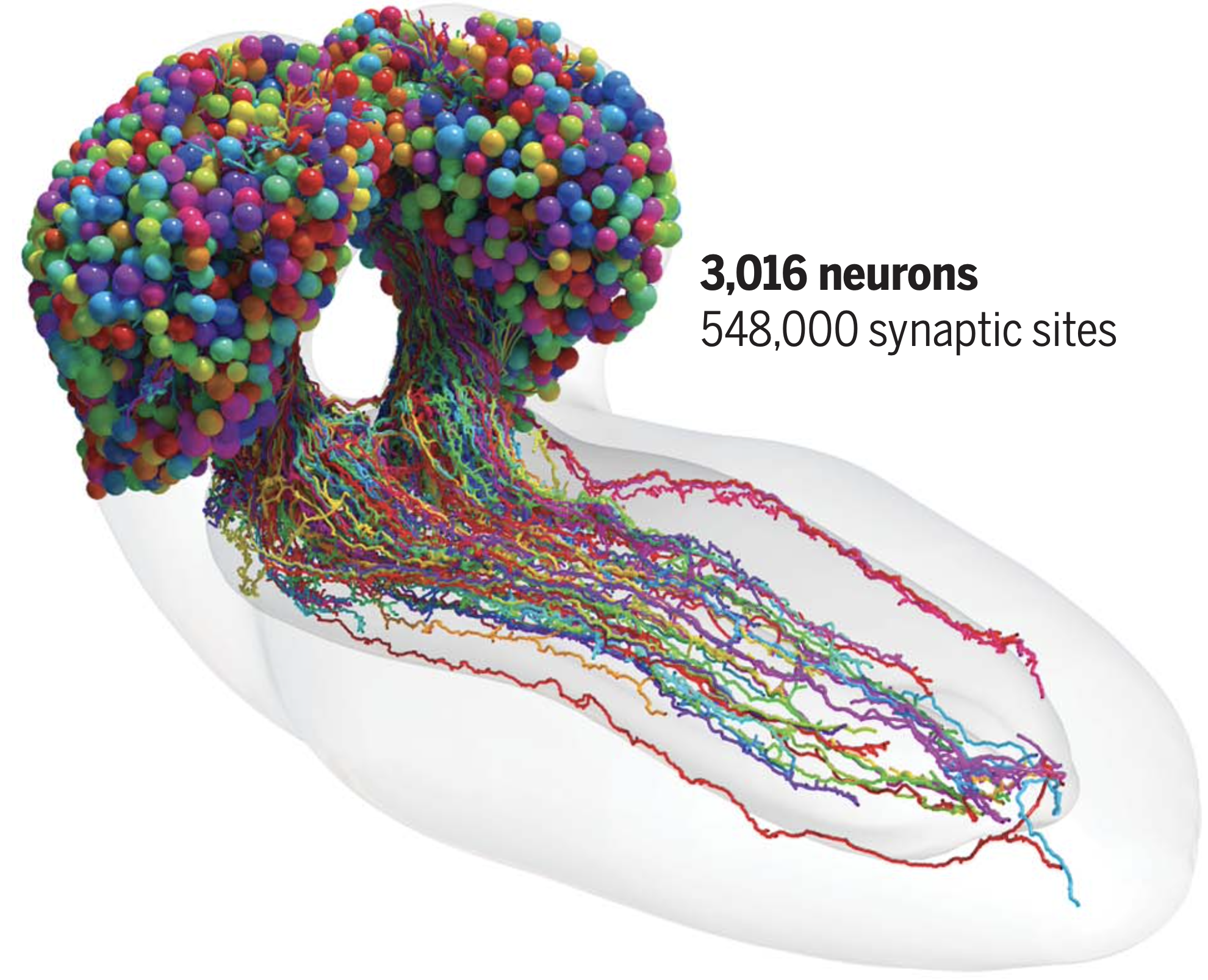

- A paper by Winding et al.

has published the entire connectome of a fruit fly larvae, identifying 3016 neurons and their 548,000 synapses. - Google Research has announced an effort to map a mouse brain (~100,000,000 neurons)

This is exciting because the fruit fly dataset presents an opportunity to identify more nuanced functions of neurons that may be present in more complex species like mice, but not in simpler species like the roundworm. This creates the requirement for algorithms that are sufficiently expressive and able to disentangle the similarities between neurons that appear different, but are functionally similar.

Furthermore, current efforts to map connectomes of increasingly complex animals makes it desirable to have algorithms that are able to scale and handle that additional complexity, with the hopes of one day discovering the algorithms that give rise to consciousness.

Background

Can we learn about human brains by studying connectomes of simpler organisms?

The primate brain exhibits a surprising degree of specialization, particularly for social objects. For instance, neurons in the face fusiform area (FFA) in the IT cortex appear to fire only in response to faces. Furthermore, individuals with lesions in or brain damage to this area lose their ability to recognize faces

In 1982, neuroscientist David Marr proposed three levels of analyses to study complex systems like the human mind: the computational level (what task is the system designed to solve?), the algorithmic level (how does the system solve it?), and the implementation level (where and how is the algorithm implemented in the system hardware?)

We might consider instead studying the connectome of a much simpler model organism, like the transparent 1mm-long nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, with whom we share an estimated 20-71% of our genes with

Unsupervised graph representation learning

The problem of subdividing neurons in a connectome into types based on their synaptic connectivity is a problem of unsupervised graph representation learning, which seeks to find a low-dimensional embedding of nodes in a graph such that similar neurons are close together in the embedding space.

A common way to identify functional clusters of neurons is through the lens of homophily, meaning that neurons serve the same function if they are within the same densely connected cluster in the connectome; however, this fails to capture the likely case that neurons with similar low-level functions span across many regions of the brain

Instead, a better approach might be to cluster neurons based on their structural equivalence, such that groups of neurons with similar subgraph structures are embedded similarly, regardless of their absolute location in the connectome. This is the approach taken by Winding et al.

Spectral embedding is a popular and general machine learning approach that uses spectral decomposition to perform a nonlinear dimensionality reduction of a graph dataset, and works well in practice. Deep learning, however, appears to be particularly well suited to identifying better representations in the field of biology (e.g., AlphaFold2

Thus, it stands to reason that deep learning might offer more insights into the functions of neurons in the fruit fly connectome, or at the very least, that exploring the differences between the spectral embedding found by Winding et al. and the embeddings discovered by deep learning methods might provide intuition as to how the methods differ on real datasets.

In this project, we explore the differences between functional neuron clusters in the fruit fly connectome identified via spectral embedding by Winding et al. and deep learning. Specifically, we are interested in exploring how spectral embedding clusters differ from embeddings learned by Variational Graph Auto-Encooders (GVAE)

We hypothesize that a deep learning technique would be better suited to learning graph embeddings of connectomes because they are able to incorporate additional information about neurons (such as the neurotransmitters released at synapses between neurons) and are able to learn a nonlinear embedding space that more accurately represents the topological structure of that particular connectome, learning to weight the connections between some neurons above others.

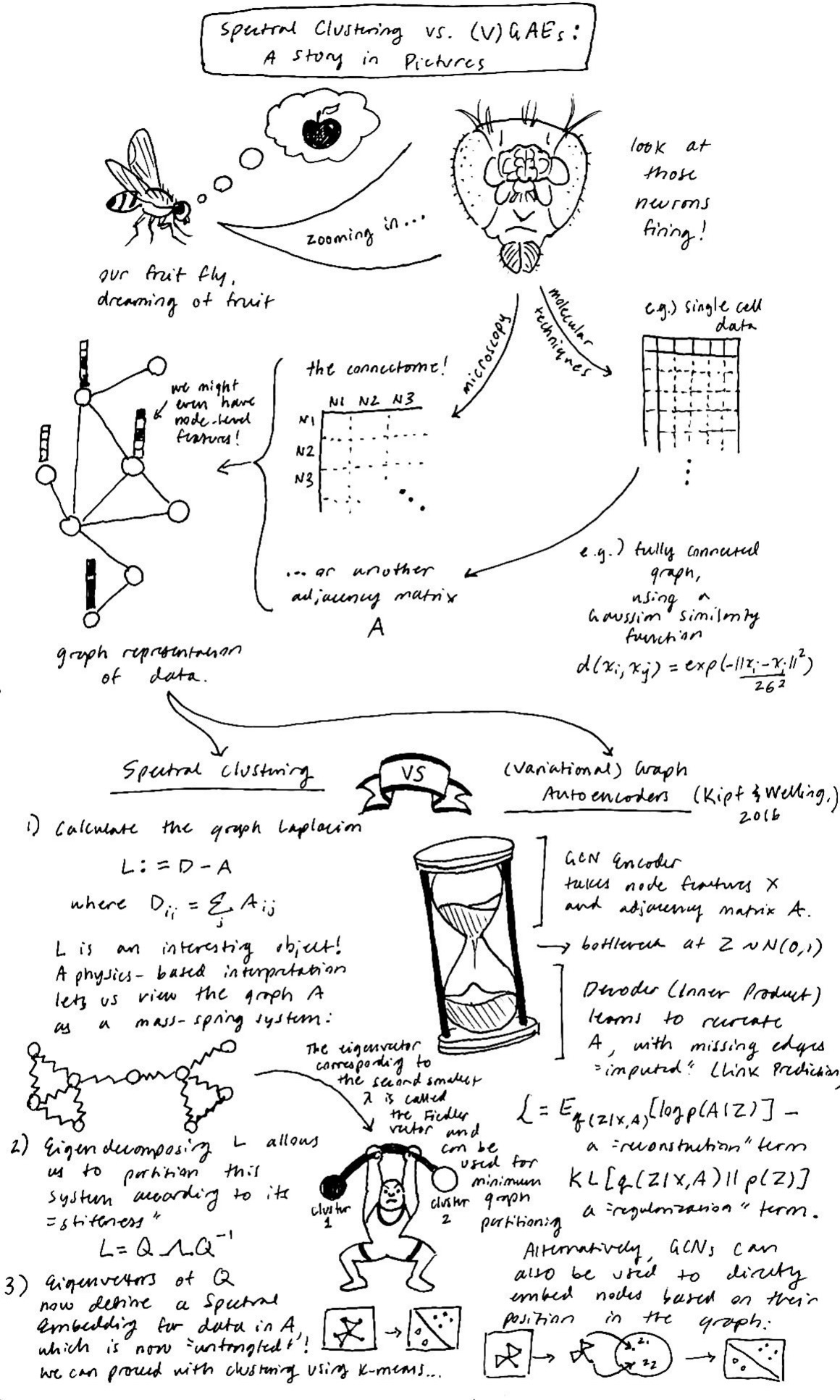

Before we can discuss the experiments, however, we first provide more detail for Spectral Embedding and Graph Variational Autoencoders and compare the two methods.

Methods

Spectral Embedding

One classical approach for understanding graph-like data comes from a class of spectral methods which use pairwise distance measures between data points to embed and cluster data. Spectral methods offer two obvious advantages when compared to other machine learning approaches. One, we can straightforwardly perform clustering for datasets which are inherently relational, like the connectome, where it is not immediately clear how a method like k-means can be used when we only have access to the relationships between data points (the “edges”) and not the node-level features themselves. Two, spectral methods are nonlinear, and don’t rely on measures like squared Euclidean distance, which can be misleading for data which are tangled in high dimensions, but which exhibit a lower intrinsic dimensionality.

So, how does spectral embedding work, exactly? In short, an adjacency matrix is first calculated from the original dataset, which is then used to compute the graph Laplacian. Next, a normalized graph Laplacian is then eigen-decomposed and generates a lower dimensional embedding space on which simpler linear clustering algorithms, like k-means, can be used to identify untangled clusters of the original data.

This class of methods makes no assumptions about the data (including cluster shape) and can be adjusted to be less noise sensitive–for example, by performing a t-step random walk across the affinity matrix for the data, as in diffusion mapping

Variational Graph Autoencoders

Although Spectral Embedding is still very popular, in recent years, more attention has been paid to the burgeoning field of geometric deep learning, a set of ideas which aim to to solve prediction or embedding tasks by taking into account the relational structure between data points. One example is the variational graph auto-encoder (VGAE), which learns to embed a complex object like a network into a low-dimensional, well-behaved latent space. Kipf and Welling (2016)

On the other hand, some have discovered that spectral embedding leads to more clear separability in low dimensional representation spaces for text data compared to GNN approaches like node2vec, which reportedly achieve state-of-the-art (sota) scores for multilabel classification and link prediction in other datasets

Thus, it remains unclear in what circumstances relatively novel geometric deep learning approaches do better compared to established and widely-explored methods like spectral learning, and particularly for novel data like the connectome. In this work, we attempt to gain deeper insights into which method is moroe well-suited to the task of connectome modeling, with the hope of learning about which method should be implemented in future connectomes, such as that of the mouse and eventually the human.

Experiments

Now that we have a good idea of how these methods compare to each other in terms of implementation, we explore them from an experimental perspective. Through our experiments, we try to quantitatively and qualitatively address the question of how connectome clusters learned by GVAE compare to the spectral clusters found in the paper. To answer this question, we make use of the fruit fly connectome adjacency matrix provided by Winding et al. as our primary dataset with the hope of answering this question for our readers.

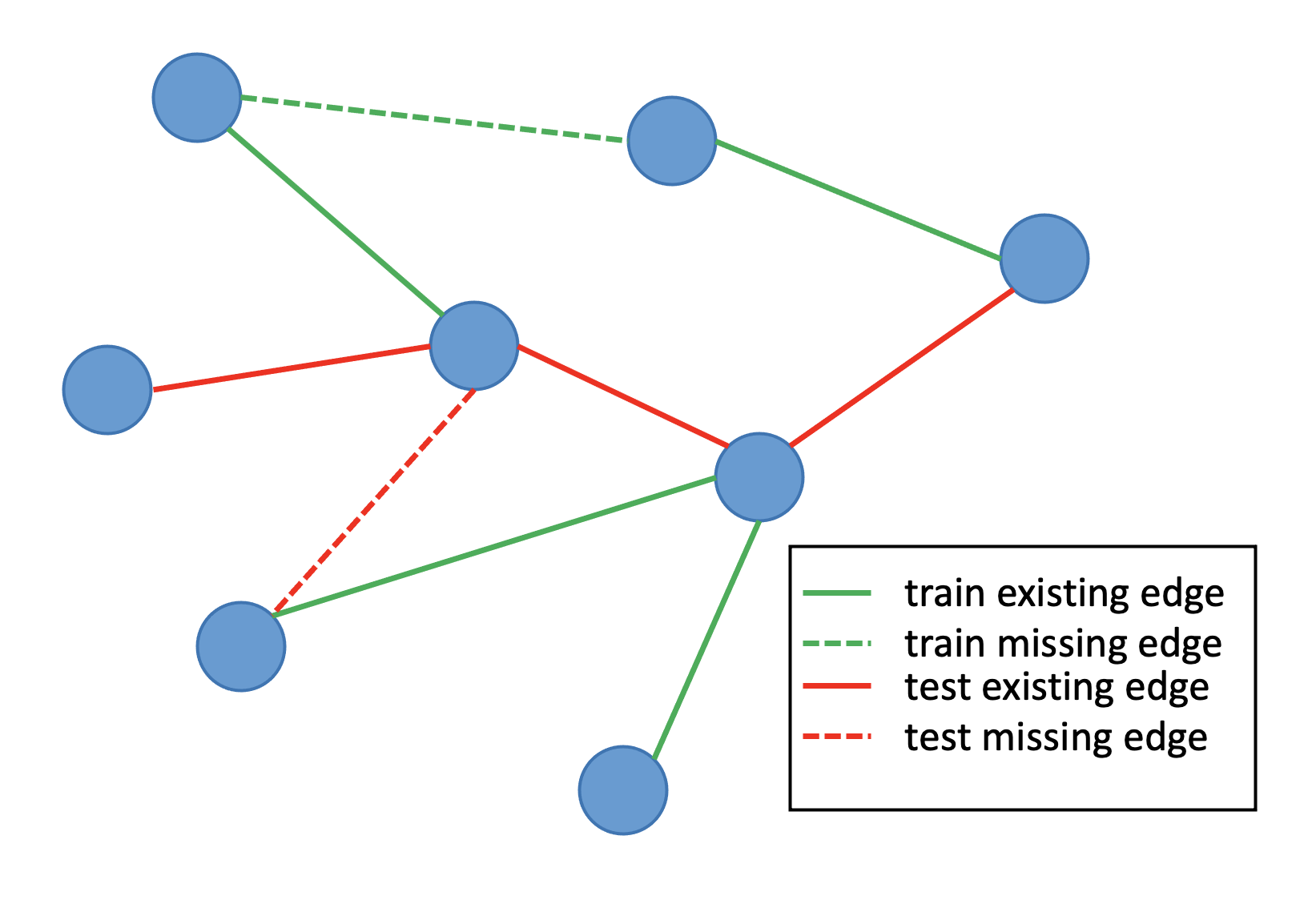

Experiment 1: Link Prediction

One common way to compare unsupervised graph representation learning algorithms is through a link prediction task, where a model is trained on a subset of the edges of a graph, and then must correctly predict the existence (or non-existence) of edges provided in a test set. If the model has learned a good, compressed representation of the underlying graph data structure, then it will be able to accurately predict both where missing test edges belong, and where they do not.

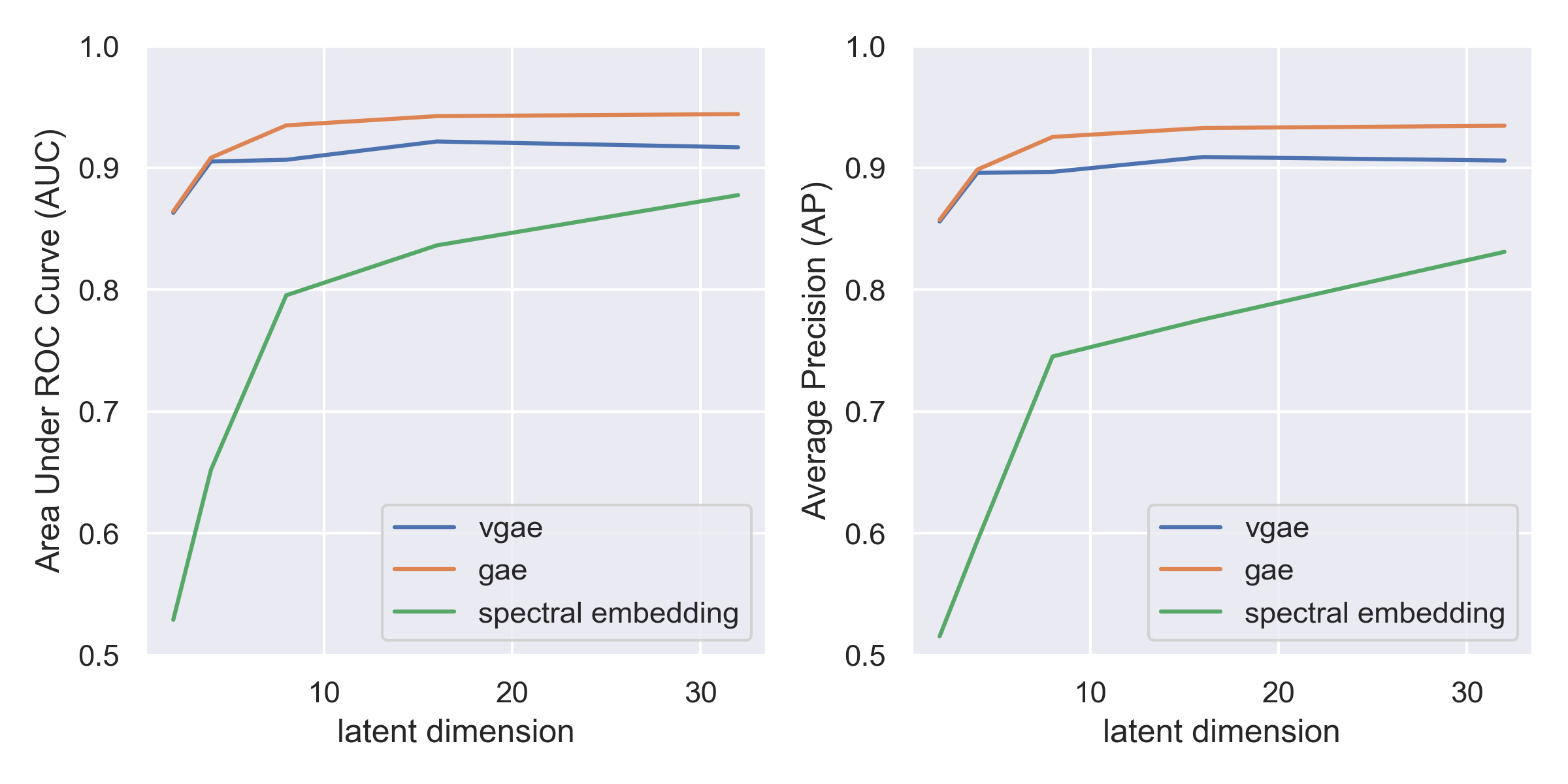

We evaluate the models by computing the area under curve (AUC) of the ROC curve, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate. A completely random classifier that does not learn anything about the underlying graph structure would get an AUC of 0.5, while a perfect classifier would have an area of 1.0.

Another metric we use to evaluate how good the models are is average precision (AP) of the precision-recall curve, which describes the consistency of the model.

In addition to comparing the models with these metrics, we also explore how robust they are to decreasing dimensionalities of the latent space. We hypothesize that if a model is able to maintain high AUC and AP, even at very low-dimensional embedding spaces, then it is likely better at capturing the structure of the connectome and is more likely to be able to scale to larger datasets, like that of the human brain one day.

Running this experiment yields the following curves, where the x-axis shows the dimensionality of the latent space, and the y-axis shows the AUCs and APs of the respective models.

From this experiment, we find that both the Graph Autoencoder (GAE) and Variational Graph Autoencoder (VGAE) perform better than Spectral Embedding methods in terms of AUC and AP, indicating that the models might be better suited to capturing the nuances in the fruit fly connectome. At the dimensionality used for spectral embedding in Winding et al., d=24, we find that the models have comparable performance, but as we reduce the dimensionality of the learned embedding, the spectral embedding method quickly breaks down and loses its ability to capture significant features in the data, with an AUC of 0.52 at a dimensionality of 2. Since a score of 0.5 corresponds to a random model, this means that the spectral embedding method is no longer able to capture any meaningful structure in the data at that dimensionality. Winding et al. gets around this by only using spectral embedding to get a latent space of size 24, and then performing a hierarchical clustering algorithm inspired by Gaussian Mixture Models, but the simplicity and robustness of the GAE model seems to show that they may be better suited to modeling the types of functional neurons present in the connectomes of animals.

Experiment 2: GVAE Latent Exploration

Although the link-prediction experiment gives us a quantitative comparison of the models, we also believe it is important to explore the latent embeddings learned by GAE to see how they qualitatively compare with the learned embeddings used in the Winding et al. work. After observing that the GAE was robust to a latent space of size 2, we decided to look specifically at if there were any similarities between the clusters found by the GAE with the 2-d embedding and the level 7 clusters published by Winding et. al. Also, although the GAE showed better overall performance, we decided to specifically explore the Variational GAE because we expect it to have a latent manifold similar to that of the Variational Autoencoders.

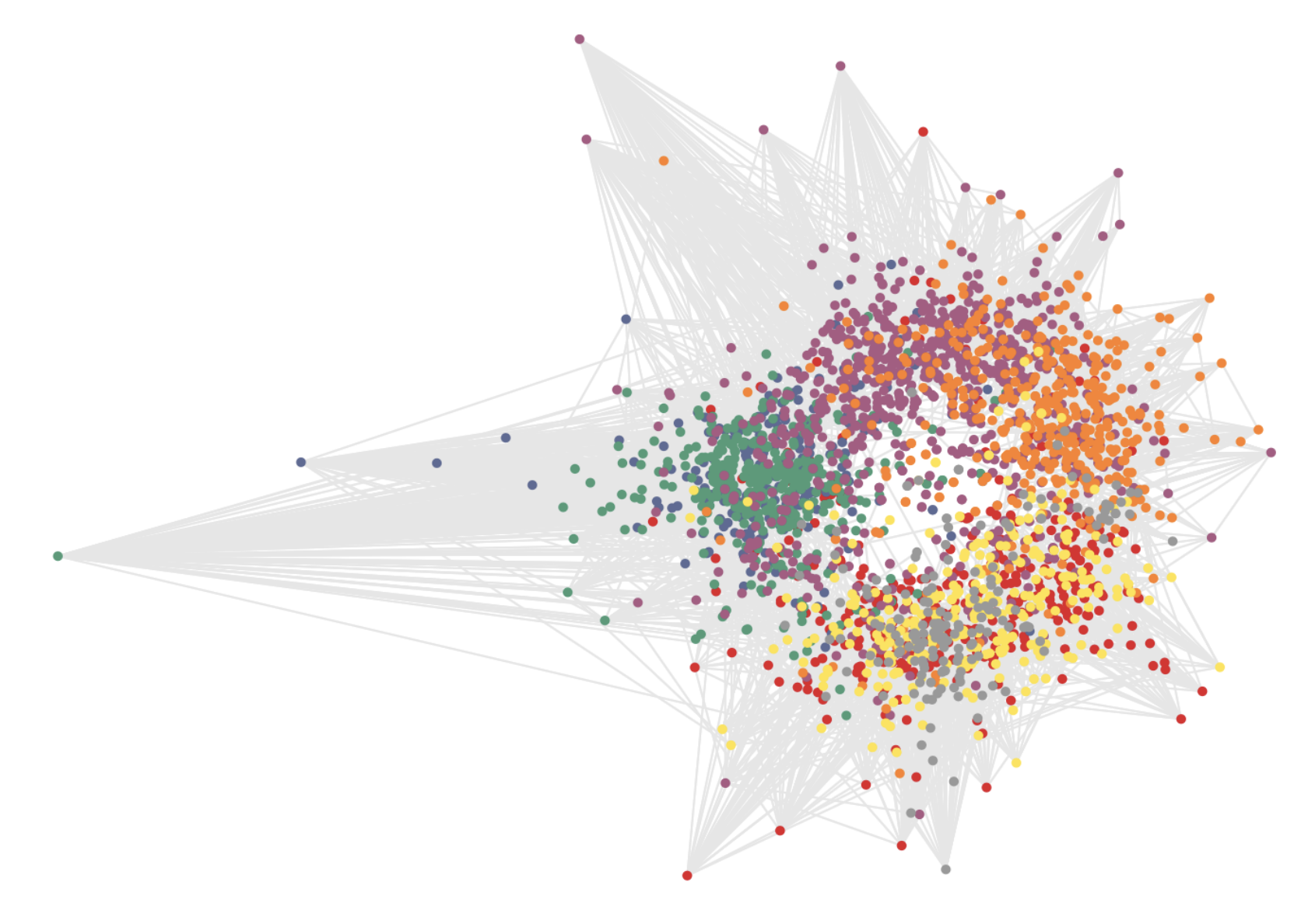

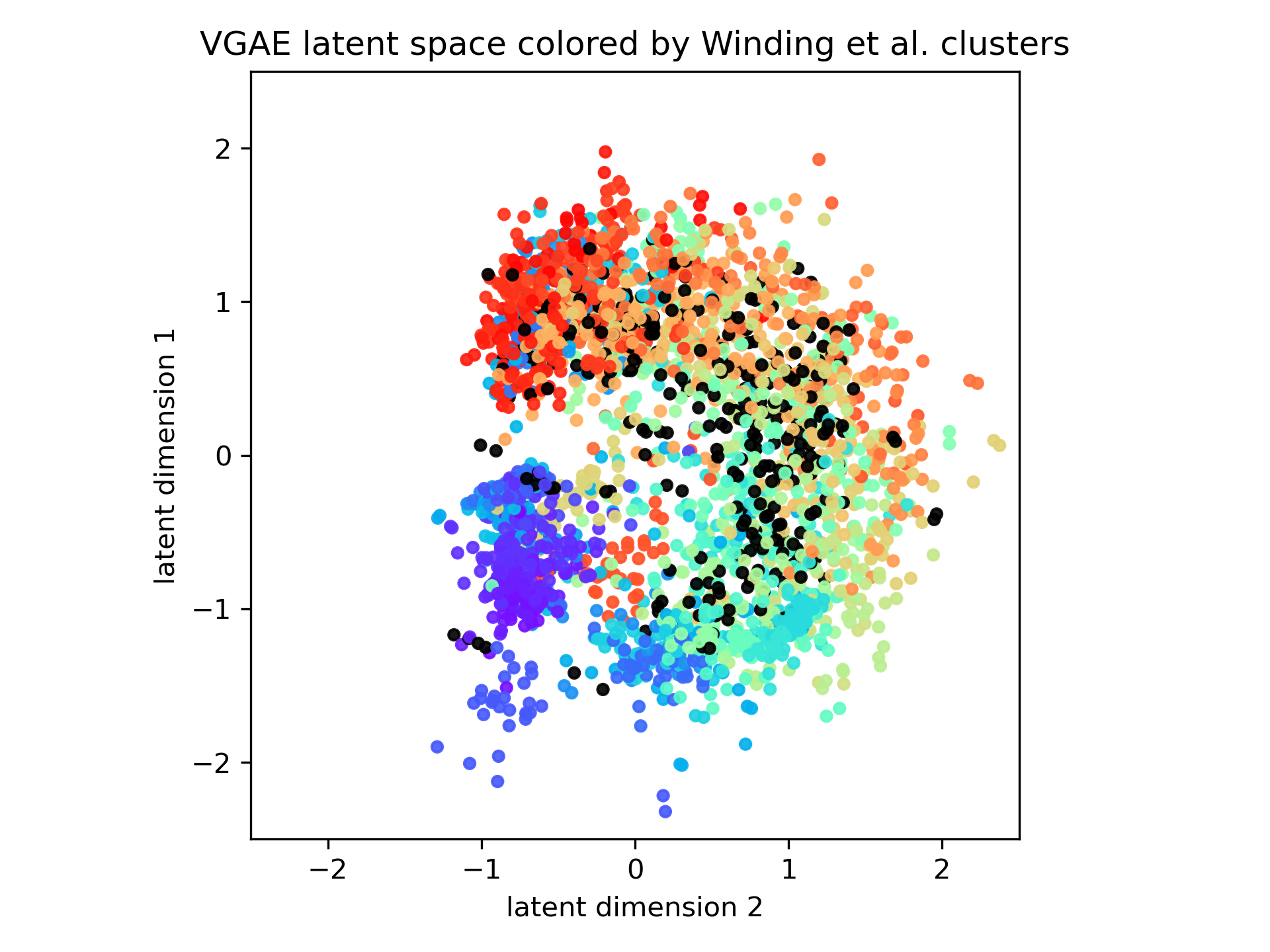

To this end, we first trained a Variational GAE with a 2-d latent space on the full fruit fly connectome and extracted the latent embedding of each node in the connectome.

With this latent embedding, we first visualized the latent space using colors corresponding to the 93 clusters identified by Winding et al. Clusters of the same color in the learned GAE latent space mean that the VGAE identified the same cluster that was identified in the Winding et. al. paper and areas where there are many colors within a cluster mean that GAE found a different cluster compared to spectral embedding.

As seen in the figure above, we find that while VGAE projects directly to a 2-d latent space without any additional clustering to reduce the dimensionality, the learned embedding still shares many similarities with the spectral embedding down to a dimensionality of 24 followed by Gaussian Mixture Model hierarchical clustering. Therefore, using VGAE to learn a direct 2-d latent space still captures much of the same information that a more complex machine learning algorithm like spectral embedding is able to.

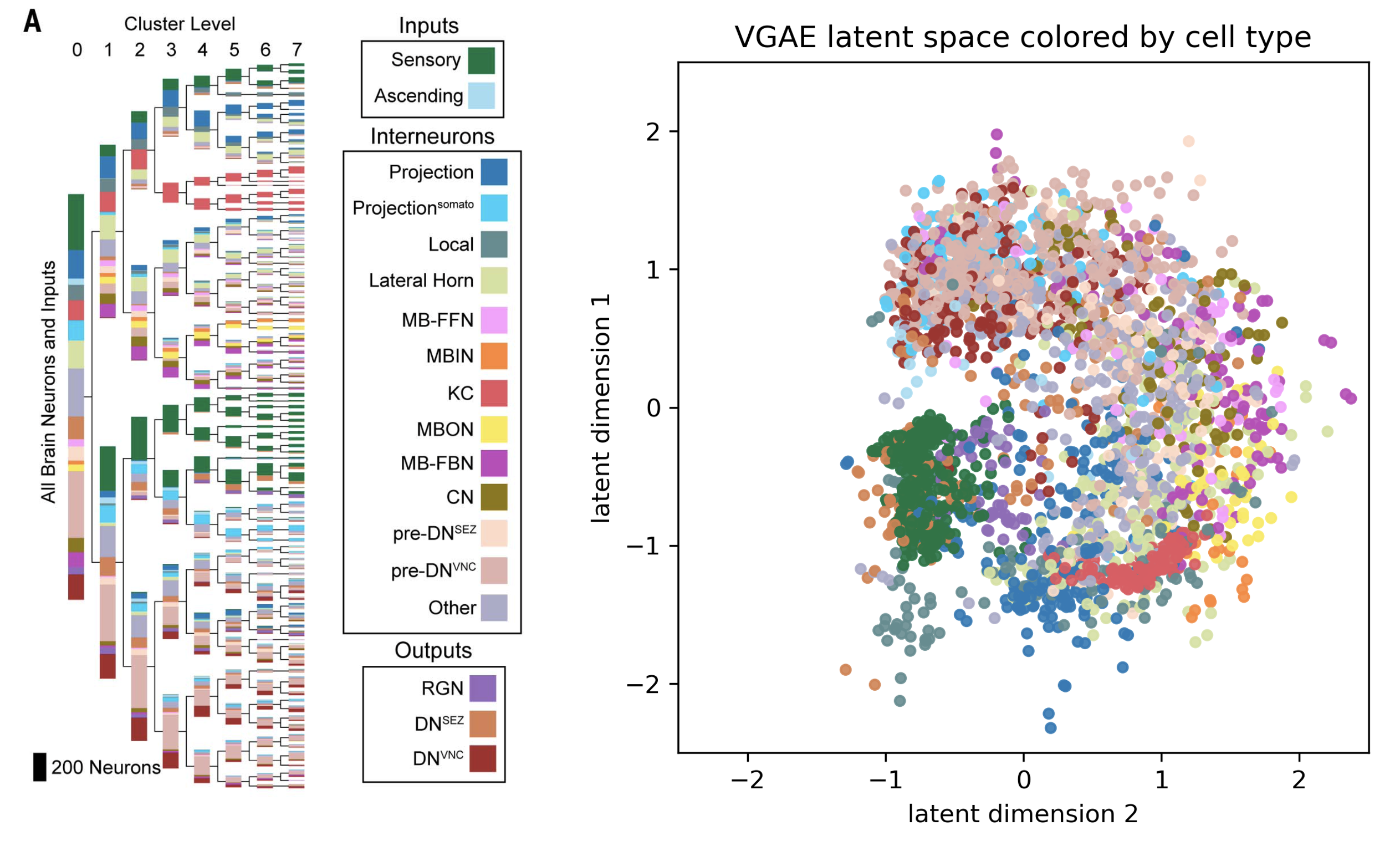

We further explored the learned latent space by looking at whether the learned embedding had any correlation with the cell types identified in the fruit fly larvae connectome. Since the VGAE only had information about the structure of the graph embedding, clusters of similar colors in this figure mean that the cell type within the cluster shared a lot of common structures, like potentially the same degree or being connected to similar types of up or downstream neurons.

We use the same color palette as the Winding et al. paper so that cell types in the level 7 clusters of the Winding et al. paper can be directly compared to the learned VGAE latent embedding.

As seen in the figure above, both spectral embedding and GVAE latent spaces capture knowledge about the cell types when trained purely on the graph structure. We believe this is because cells of this type have similar properties in terms of the types of neighboring neurons they connect to in the connectome, and they may also have special properties like higher degree of connections.

In particular, it is interesting that sensory neurons and Kenyon cells are very well captured by both embeddings, and that MBIN cells and sensory neurons are clustered together by both their spectral embedding algorithm and VGAE.

Discussion

Our preliminary investigations show that deep learning algorithms such as Graph Autoencoders (GAEs) and Variational Graph Autoencoders (VGAEs) are able to capture at least as much nuance and information about function as spectral embedding algorithms. In addition, they come with the following advangates:

- With their current implementation, they can easily be run on a GPU, while common spectral embedding algorithms in libraries such as scikit learn are only designed to work on CPUs. Since we take a deep learning approach, our GNN method can use batches optimized via Adam, while spectral embedding only works if the entire adjacency matrix fits in memoruy. This makes deep learning methods better able to scale to larger datasets such as the mouse connectome that may come in the next few years.

- As shown in experiment 2, GAEs and Variational GAEs are able to directly learn a robust embedding into a 2-d space without any additional clustering, making interpretation easy and fast. We suspect that because of its higher performance at embedding connectomes to such low dimensions compared to spectral embedding which performs only marginally better than a random algorithm at such low dimensions, VGAEs must be capturing some addiitonal nuance of the graph structures that spectral embedding is simply not able to encode.

- Comparing the 2-d embeddings of VGAE to the clustered 24-d spectral embeddings found in Winding et al. we find that even when compressing to such a low-dimensional space, the semantic information captured does in fact match that of spectral embedding at a higher dimensional space. Coloring by cell type shows that it also captures information about the function of neurons, with similar neuron types being clustered together even when they are located all over the brain, such as Kenyon cells. Cells of the same type likely serve simlar functions, so in this respect, VGAE is able to capture information about the function of cells using only knowledge of the graph structure.

However, VGAE does not come without its limitations. One large limitation we found while implementing the architecture is that it currently requires graphs to be undirected, so we had to remove information about the direction of neurons for this work. Connectomes are inherently directed, so we likely missed some key information about the function of graphs by removing this directional nature of the connectome. Although this is not explored in our work, one simple way to fix this would be to add features to each node corresponding to the in-degree and out-degree of each neuron.

This brings us to the another limitation of our study, which is that we did not explore adding features to neurons in our connectome with the VGAE algorithm. Past work on GAEs has shown that adding features leads to better model results

One final limiation is that our model only trains on a single connectome. This means that we aren’t able to capture the variation of connectomes within a species. Maybe one day, we will be able to scan connectomes of people in the same way that we are able to scan genomes of people, but that day is likely still far away. We might be able to help this by using the generative compoment of the VGAE to create brains that are physically feasible given the structure of a single connectome, but it would be hard to test. Since we are currently only looking at the connectome of a single species, we likely aren’t capturing an embedding space that finds functionally similar neurons in different animals such as C. elegans, which we may be able to do in future work.

Conclusion

In this work, we asked if Deep Learning techniques like Variational Graph Autoencoders could learn something about the functions of cells in a connectome using only the graph structure. We found that VGAE did in fact capture relevant structures of the graph, even in the undirected case. It performed similarly to spectral embeding, even when embedding directly into a visualizable 2-d latent space. In the future, we may be able to learn about neurons that serve the same purpose across species, or learn about the underlying low level syntactic structures like for-loops or data types that our brain uses to encode consciousness, vision, and more.