Combining Modalities for Better Molecular Representation Learning

Introduction

Importance of molecular representation learning

Molecular Representation Learning (MRL) is one of the most important tasks in molecular machine learning, drug design, and cheminformatics.

Different ways to represent molecules

The challenge of learning molecular representations is more complex than in fields like computer vision or natural language processing. This complexity stems from the variety of methods available for encoding molecular structures and the assumptions inherent to each representation. Primarily, there are four ways to represent molecules:

- Fingerprints. One of the oldest ways to represent molecules in Quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) modelling. Molecular fingerprints are binary vectors that encode the presence or absence of certain substructures in the molecule. Fingerprints were one of the first ways to get the initial representation of molecules in machine learning problems.

- String representation (e.g. SMILES strings). This approach involves encoding molecular fragments as tokens to form a string. This initial molecules encoding is widely used in generative molecular modeling.

- 2-D graph. A popular and intuitive approach where molecules are represented as graphs, with atoms and bonds corresponding to nodes and edges, respectively. With advancements in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) architectures,

this format is extensively used in molecular property prediction. - 3-D graph. The most detailed representation, which includes spatial information about atoms and bonds in addition to the graph structure. Although obtaining 3-D graph representations is challenging, models based on this approach often demonstrate superior performance. Various modeling techniques are applied to 3-D graphs, including invariant and equivariant GNNs.

Given these diverse approaches, this work aims to explore various molecular representations and their potential combination for enhanced performance in downstream tasks, such as molecular property prediction. Additionally, this blog post seeks to analyze the representations of small molecules by comparing nearest neighbors in the latent chemical space. We also investigate representations learned by language models trained on SMILES strings.

Methods

Data

In this study, we utilized the QM9 dataset to train and evaluate our models. Comprising approximately 133,000 small organic molecules, the dataset includes molecules with up to nine heavy atoms (specifically Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen, and Fluorine) and 19 distinct properties. As a well-established benchmark in molecular property prediction research, QM9 offers a comprehensive foundation for our analysis.

Our primary focus was on predicting the free energy $G$ at 298.15K. To ensure a robust evaluation, we divided the dataset using Murcko scaffolds

Models

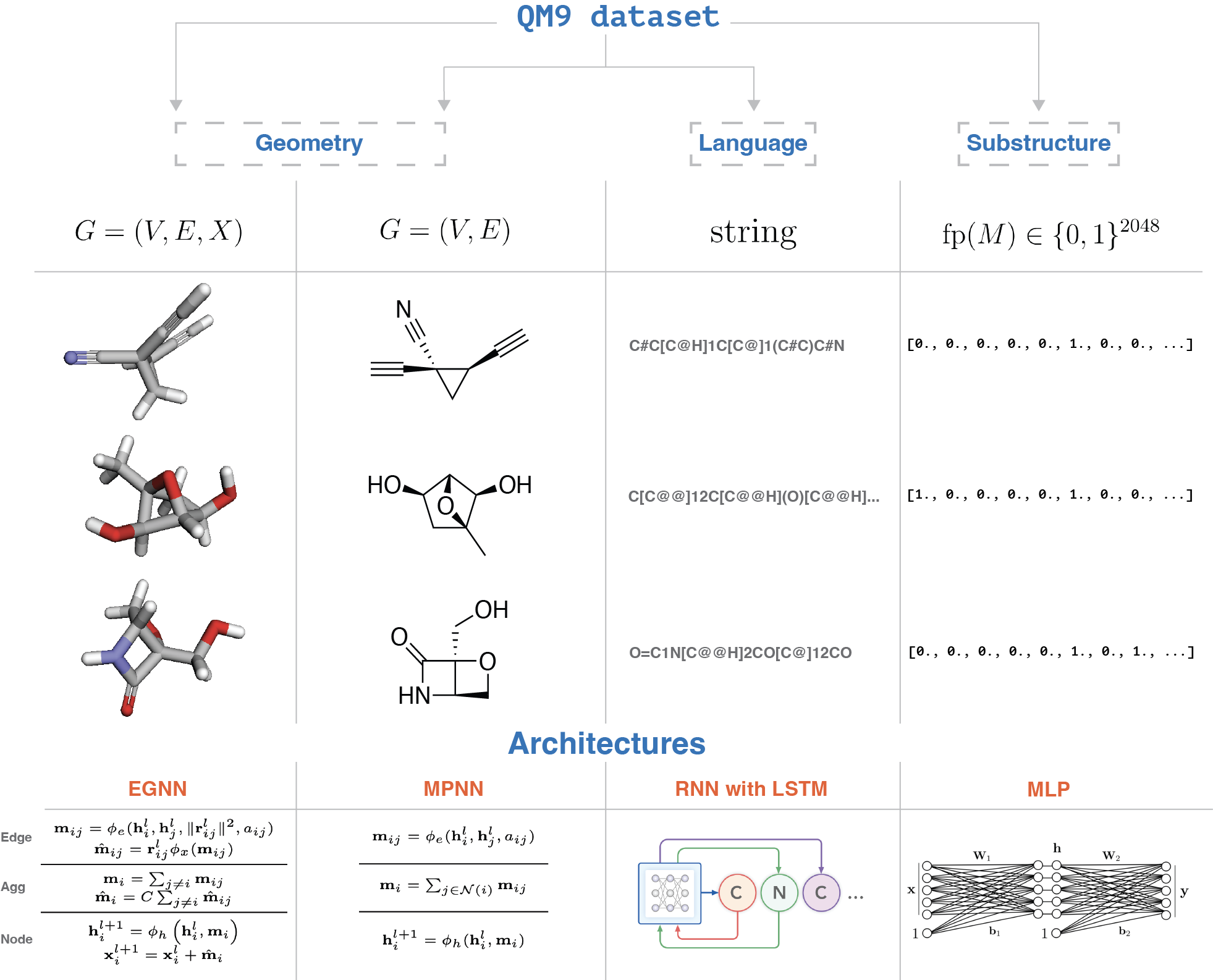

The illustration of the overall approach is presented in Figure 1.

We use the following models to learn the representations of molecules:

- Fingerprint-based model. Utilizing Morgan fingerprints

with a radius of 2 and 2048 bits, we developed a multilayer perceptron (MLP) featuring six layers, layer normalization, and a varying number of hidden units (ranging from 512 to 256). This model focuses on learning representations from molecular fingerprints. -

SMILES-based model. For the representation of SMILES strings in the QM9 dataset, we employed a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with LSTM cells, comprising three layers and 256 hidden units. This model learns to predict the next token in a SMILES string based on the previous tokens, using cross-entropy loss for training: \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{CE}} = -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \log p(x_t | x_{<t})\)

- 2-D graph-based model. To handle 2-D graph representations of molecules, we used a Message Passing Neural Network with four layers, 256 hidden units, sum aggregation, mean pooling, and residual connections between convolution layers. The model updates the nodes’ hidden representations as follows:

- 3-D graph-based model. While there are many different architectures to model points in 3-D space, we decided to use one of the simplest architectures — E(n) Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN)

that is equivariant to rotations, translations, reflections, and permutations of the nodes. We used 4 layers, 256 hidden units, sum aggregation, mean pooling and residual connections between convolution layers to learn the representations of 3-D graphs of molecules that updates the nodes hidden representations according to the equations given in the Figure 1.

Training

We trained all models using the Adam optimizer with learning rate of $1\cdot10^{-3}$, batch size 32, and 100 epochs. We additionally used ReduceLROnPlateau learning rate scheduler. We used the mean absolute error (MAE) as the metric for evaluation.

Evaluation

We used several combination of modalities to evaluate the performance of the models:

- MPNN + FPs: This model integrates the representation learned by the Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) with the MLP trained on fingerprints, featuring 256 hidden units. It concatenates the representations from MPNN and MLP, using an MLP layer for the final target value prediction.

- EGNN + FPs: Similar to the previous model but uses the representation learned by the EGNN.

- EGNN + MPNN: This configuration combines the representations from EGNN and MPNN, followed by an MLP for target value prediction.

- MPNN + RNN: This model merges representations from MPNN and a pretrained Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The RNN’s encodings remain static and are not updated during training. However, this model did not converge and was excluded from the final evaluation.

The results of evaluation of different models on the QM9 dataset are presented in Figure 2.

Analysis

Comparison of different models

As depicted in Figure 2, the EGNN model demonstrates superior performance. A likely explanation is that the QM9 dataset’s labels were calculated using computational methods that leverage the 3-D structure of molecules. The 3-D representation, therefore, proves most effective for this task, with the EGNN adept at capturing crucial 3-D interactions for predicting the target value. Interestingly, simple concatenation of hidden representations seems to dilute the information, resulting in inferior performance. This suggests that combining modalities is a complex endeavor, requiring thoughtful architectural design.

Nearest neighbors analysis

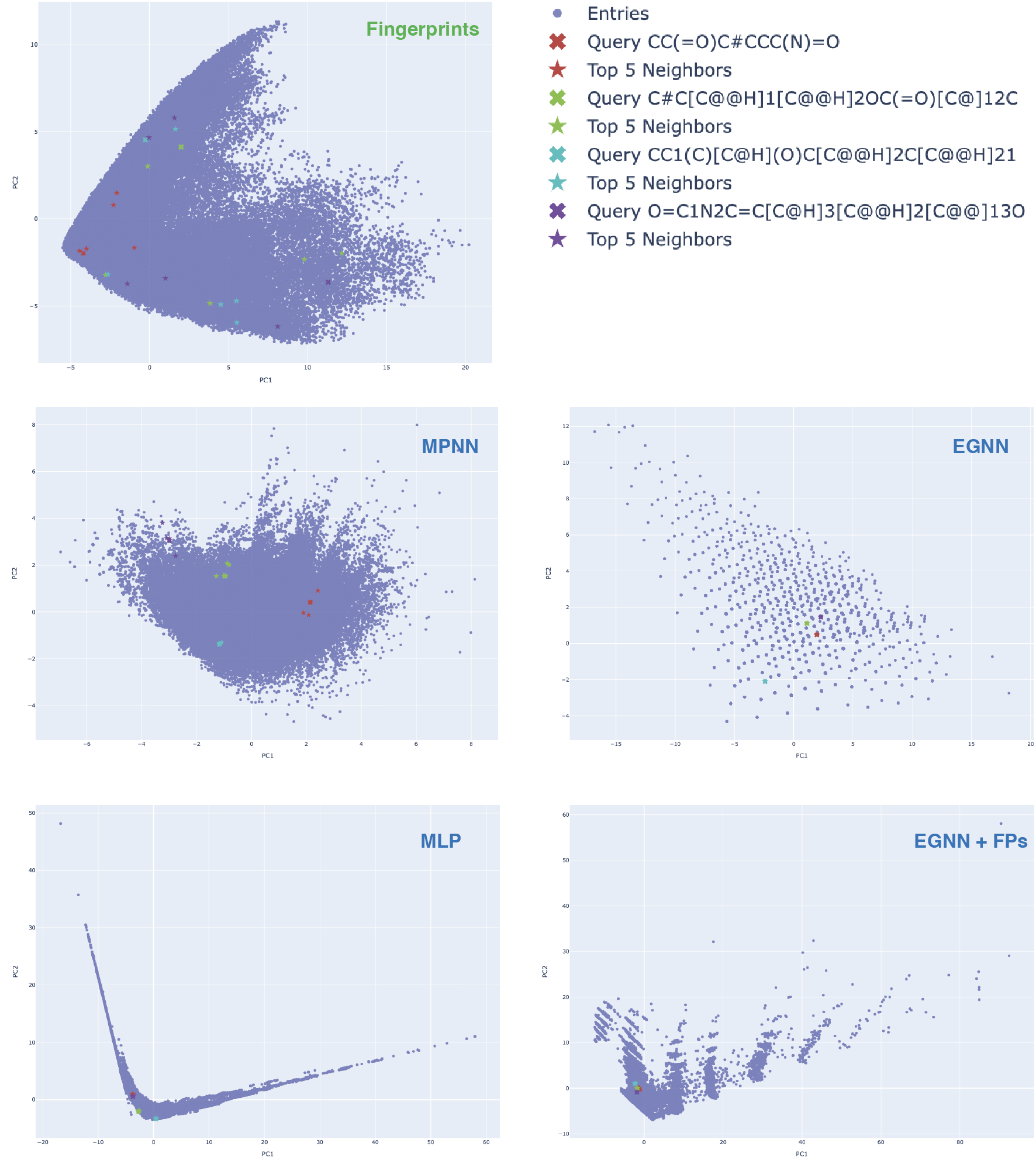

After the training of the models we performed the nearest neighbors analysis to compare the learned representations of molecules. We took the learned representations of the molecules in the test set and computed the nearest neighbors in the latent chemical space using cosine similarity. Additionally we plotted the PCA reduced representations (Figure 3) and analyzed the nearest neighbors for 4 different molecular scaffolds.

There are several interesting observations from the nearest neighbors analysis:

- In case of fingerprints reductions the nearest neighbors are far away from the queried molecules in the latent chemical space.

- For the reduced learned representations of the molecules in the test set we can see that the nearest neighbors are very close to the queried molecules in the latent chemical space. This is expected as the models were trained to predict the target value and therefore the representations of the molecules that are close in the latent chemical space should have similar target values.

- The bottom right plot of Figure 3, showcasing the EGNN + FPs combination reveals very interesting pattern — the reduced chemical space reminds the combination of the reduced chemical spaces of the EGNN and FPs. EGNN’s reduced chemical is more “sparse”, while the representation that learned by MLP is more dense but much more spread out. Another interesting observation is that the combined chemical space is more structured due to the presence of some clustered fragments, which is not present in case of both EGNN and MLP.

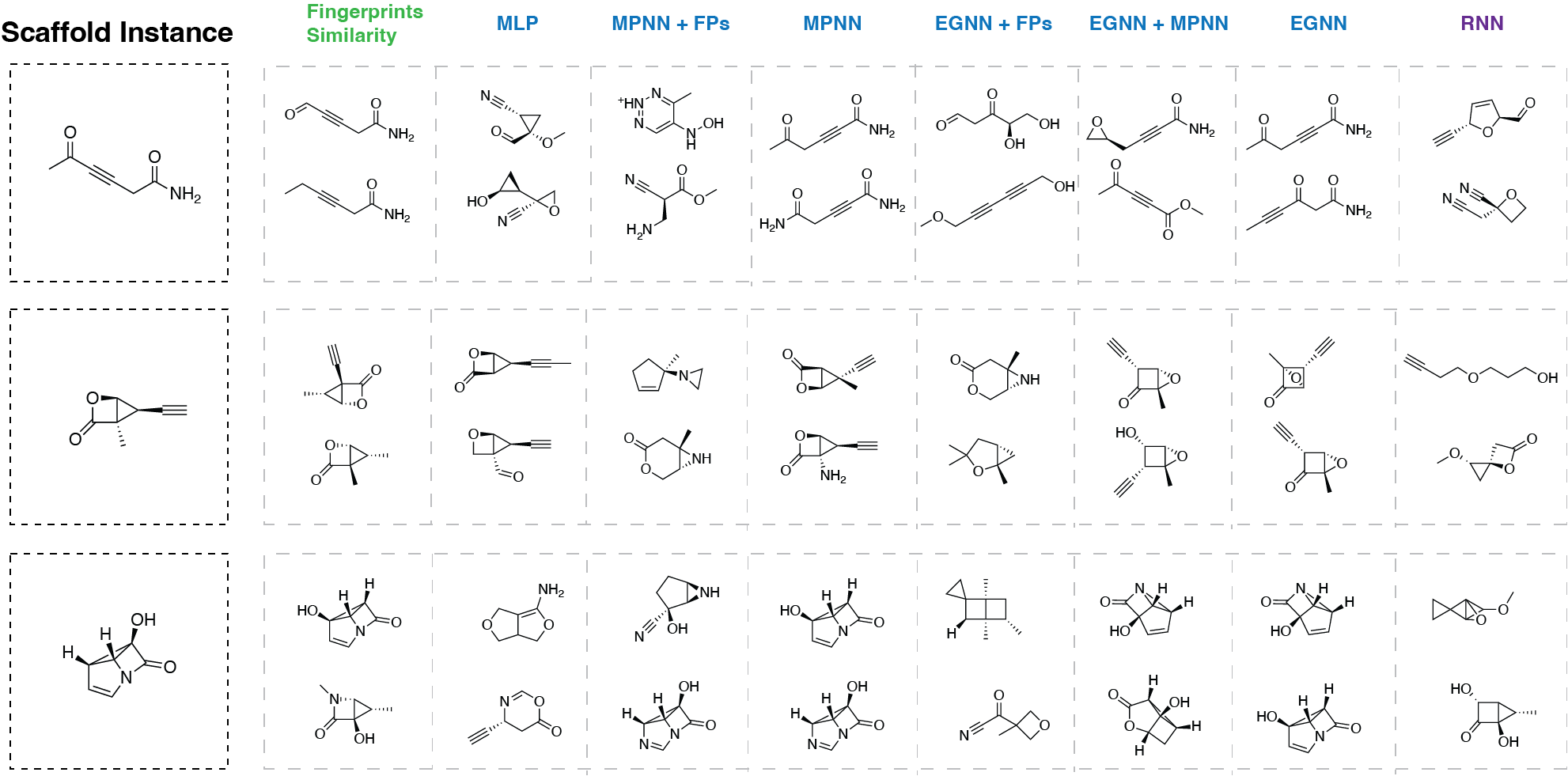

Additionally we analyzed the nearest neighbors for 4 different molecular scaffolds. The results for 3 of them are present in Figure 4.

From the Figure 4 we can make some additional observations:

- For the fingerprints similarity, molecules are very similar to the queried molecule. This is expected results because the molecules with the highest matches in the fingerprints are the most similar to the queried molecule. Although, for the third example the second closest molecule is not very similar to the queried molecule.

- MPNN, EGNN as well as their combination return the molecules that are very similar to the queried molecule. Because the model was trained to predict the target value, the nearest neighbors are molecules with similar target values (this is not guaranteed for the fingerprints similarity because substructures can be combined in different ways potentially leading to very different molecular properties).

- In case of MLP trained on fingerprints, the nearest neighbors can have very different scaffolds. This agrees with the performance of the model on the QM9 dataset — the model is not able to fully capture the molecular structure and therefore the nearest neighbors can have very different scaffolds even though the initial representations were the ones retrieving the most similar molecules (fingerprints).

- Interestingly, in case of RNN trained on SMILES strings, the nearest neighbors can have very different scaffolds. This result is expected because RNN was trained to predict next token in the sequence and therefore the nearest neighbors are the molecules with similar SMILES strings. For example, first molecule contains triple bond between two carbon atoms. In the case of the second closest neighbor for first scaffold instance there are two triple bonds between carbon and nitrogen atoms. The scaffold is different, but the SMILES strings are similar.

Overall, the key takeaway is that the more effectively a model performs in the supervised learning phase (excluding the RNN), the more meaningful its nearest neighbors are in terms of molecular structure resemblance. While fingerprint similarity still yields closely matched molecules, the results are not as insightful as those from GNNs, which capture molecular structures with greater nuance and expressiveness.

Conclusion

Results of modalities mixing

Modalities mixing is a very interesting and promising approach for the problems in the field of molecular machine learning. However, architectures should be desinged carefully to achieve the best performance. In our work we showed that simple concatenation of the representations learned by different models can lead to worse performance on the downstream tasks.

Future work

The obvious direction of future work — to experiment with different architectures for modalities mixing. Another interesting direction is to use the mixed modalities for the generative molecular modeling as string methods still perform better than majority of 3-D generative approaches even though the latter one is more natural.