Transformers vs. RNNs: How do findings from real-world datasets relate to the theory?

Transformers have rapidly surpassed RNNs in popularity due to their efficiency via parallel computing without sacrificing accuracy. Transformers are seemingly able to perform better than RNNs on memory based tasks without keeping track of that recurrence. This leads researchers to wonder -- why? To contriubte towards answering that question, I'll analyze the performance of transformer and RNN based models on datasets in real-world applications. Serving as a bridge between applications and theory-based work, this will hopefully enable future developers to better decide which architecture to use in practice.

Introduction & Motivation

Since their invention, transformers have quickly surpassed RNNs in popularity due to their efficiency via parallel computing

Background & Prior Work

Recurrent neural networks (RNN) are a type of neural network that were previously considered state-of-the-art for generating predictions on sequential data including speech, financial data, and video

However, since Transformers were invented in 2017, they have rapidly made the use RNNs obsolete

While Transformers were accepted to perform better, the question remained – why? Transformers do not keep track of recurrence but are somehow able to successfully complete memory-based tasks. Liu et al aimed to answer this question by exploring how transformers learn shortcuts to automata

Current research in the RNN space is largely focused on trying to leverage their inherently linear complexity to its advantage

Methods & Results

Data

The first dataset I used was Yahoo Finance’s stock dataset, accessible through the yfinance API. I specifically looked at the closing price data from the S&P500 stock group which represents the stocks from the 500 largest companies. The second dataset I used was from Kaggle (available here). This dataset captures ECG data. I specifically used the abnormal and normal sub datasets that contained single-heart beat single-lead ECG data.

Software

I ran all of the code for this project using Python 3.10 in Google Colab. The APIs numpy, scipy, matplotlib, seaborn, keras, tensorflow, and yfinance were all used. The notebook used for the stock experiements is available here and the ECG experiments here.

Stock Model Comparisons

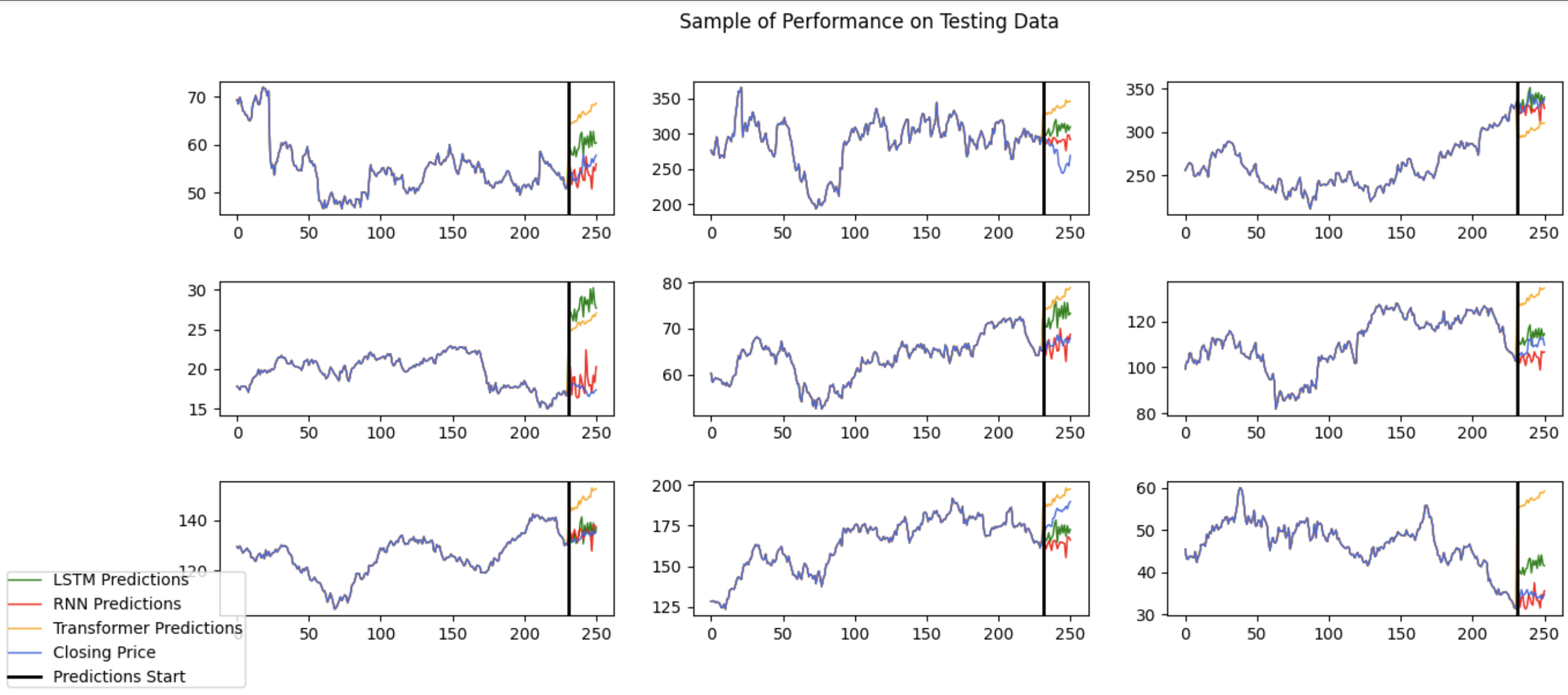

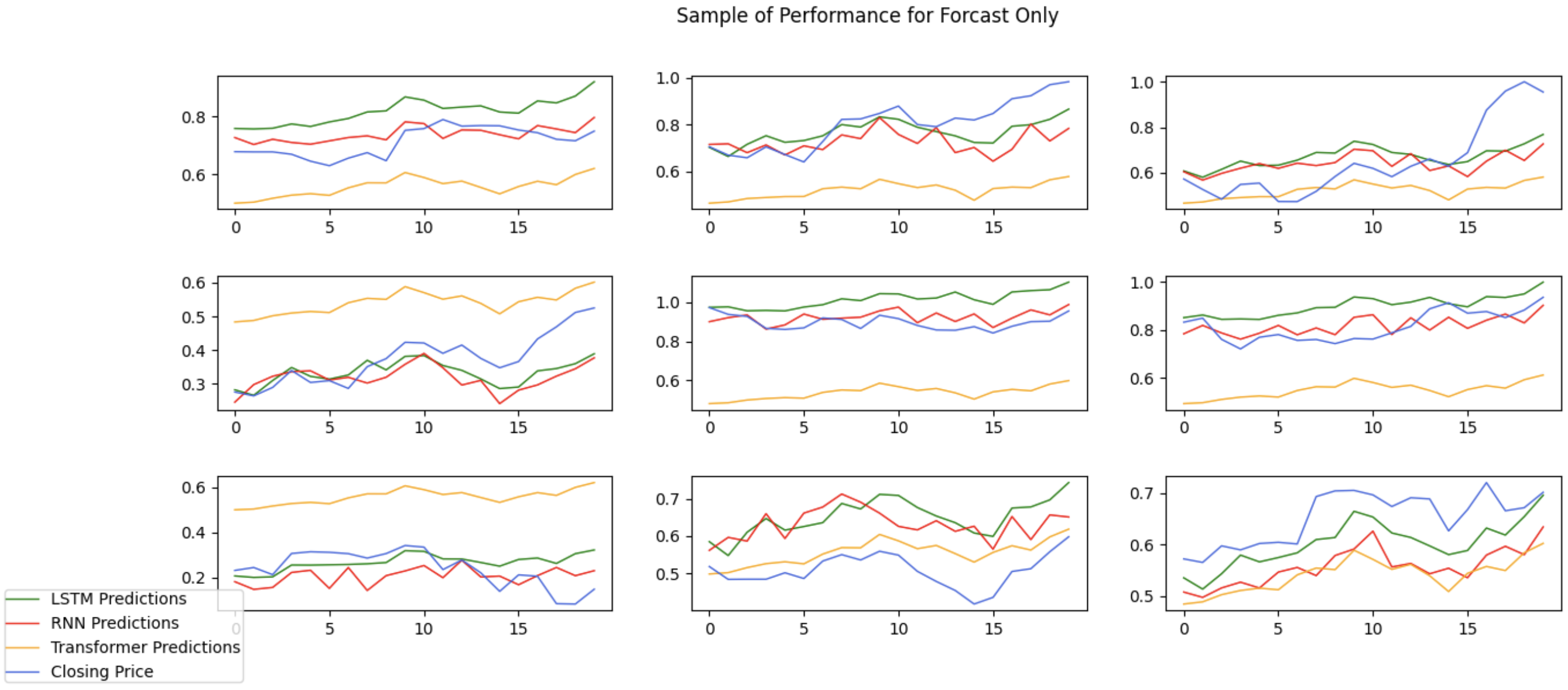

I began my experiments by loading and visualizing the data. I wanted to compare the transformer and RNN models on a time-series prediction so I decided to use 11 months of data to predict the next 1 month behavior. To do this, I loaded data from July 1st, 2022 to July 31st 2022. Of note, the stock market is closed during weekends and holidays, so there were 251 days in my dataframe, and I trained on the first 231 days to predict the last 20. I then used an 80/20 train and test split.

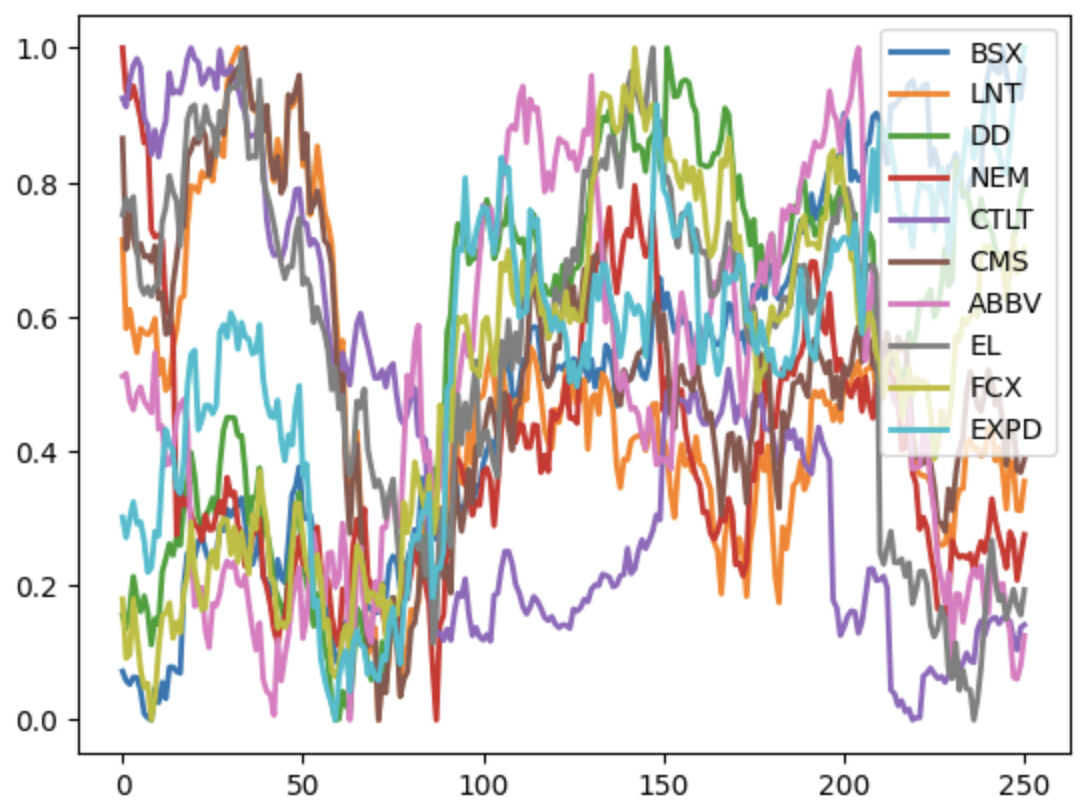

I also visualized several iterations of ten random samples to better understand the dataset and ensure that I was preprocessing correctly.

Once I had the data set up, I began to build each model. In addition to a simple RNN architecture and a Transformer model, I also built an LSTM model which is a specialized subset of RNNs that aim to solve a vanishing gradient problem in traditional RNNs

In building the models, I tried to keep them all as simple and equivalent as possible for a fair comparison. This was simple for the LSTM and RNN, I just used two LSTM (or RNN) layers followed by a linear layer and then an output linear layer. Because of the different architecture of transformers, it didn’t seem possible to create a completely equivalent architecture. However, I tried to approximate this by having just a singular attention layer that didn’t have a feed foward network component and only had a standard layer normalization and then a multiheaded attention wiht 2 heads (the same number of layers for RNN/LSTM with the head size equivalent to the RNN/LSTM layer size). I followed this with a pooling layer, a linear layer (with the same size as the RNN/LSTM linear layer) and a linear output layer. I trained all models with a batch size of 25 and 30 epochs.

For each model, I measured RMSE for the predictions (used for accuracy), time used to train the model, memory used to train the model, number of parameters, and storage used for parameters. The results are shown in the following table.

| Model | RMSE | Memory in Training (KB) | Time to Train (s) | Parameters (#) | Memory for Parameters (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 155.61 | 16575097 | 151.76 | 54190 | 211.68 |

| RNN | 149. 07 | 4856823 | 67.25 | 16750 | 65.43 |

| Transformers | 36.46 | 3165225 | 87.00 | 2019 | 7.89 |

As expected, the LSTM model runs much slower with higher memory usage which is consistent with literature models

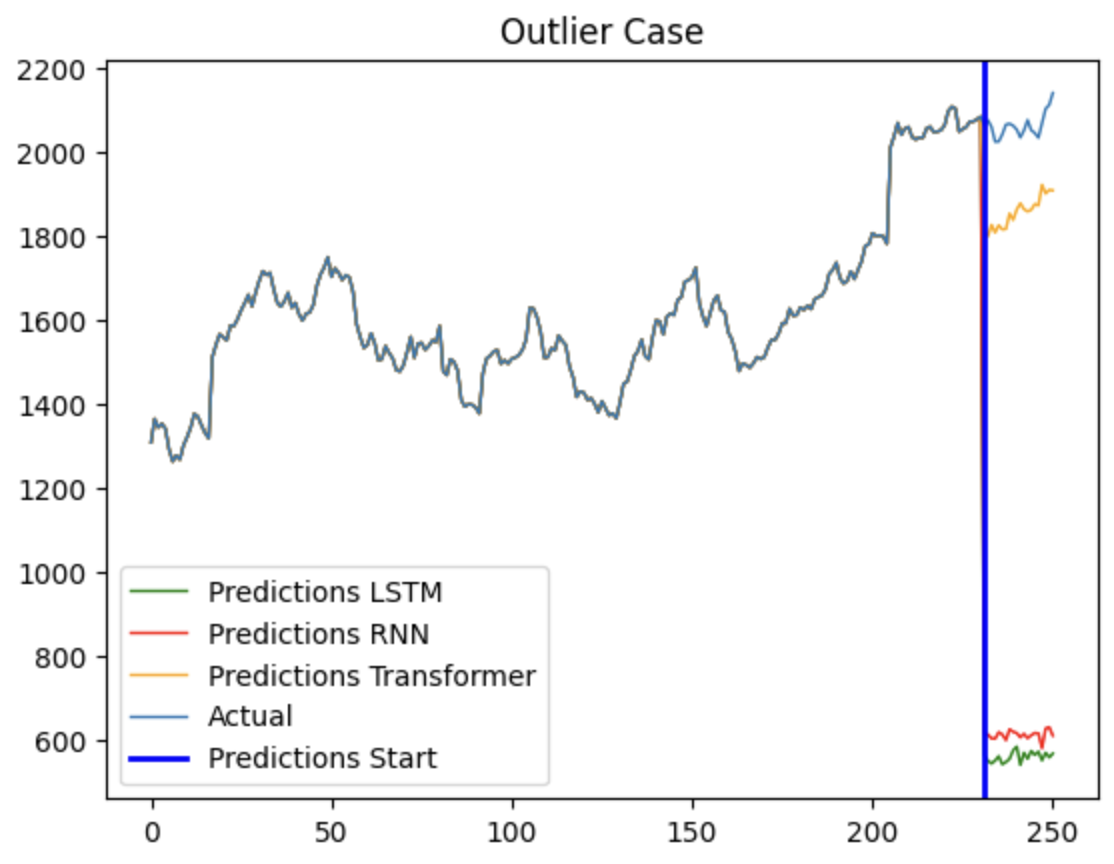

Besides noting that the models all did fairly well given their simplicity, this was puzzling. Addditionally, when I reran the models, I noted that the RMSE values for the LSTM/RNN models varied wildly with results between 50-550 whereas transformer’s performance was consistently around 35. To investigate, I printed out the RMSE for each prediction and analyzed them. I found that most errors were fairly small but there were a couple very large errors that ended up skewing the overall reported average. In visualizing that outlier and performance between the models, I saw that the prices for the outliers were much higher than most stocks, making the LSTM/RNN models predict a much lower price.

Transformers still do okay here, likely do to the first normalization layer I used. Thus, to make the problem more equal, I decided to normalize all of the data at the onset.

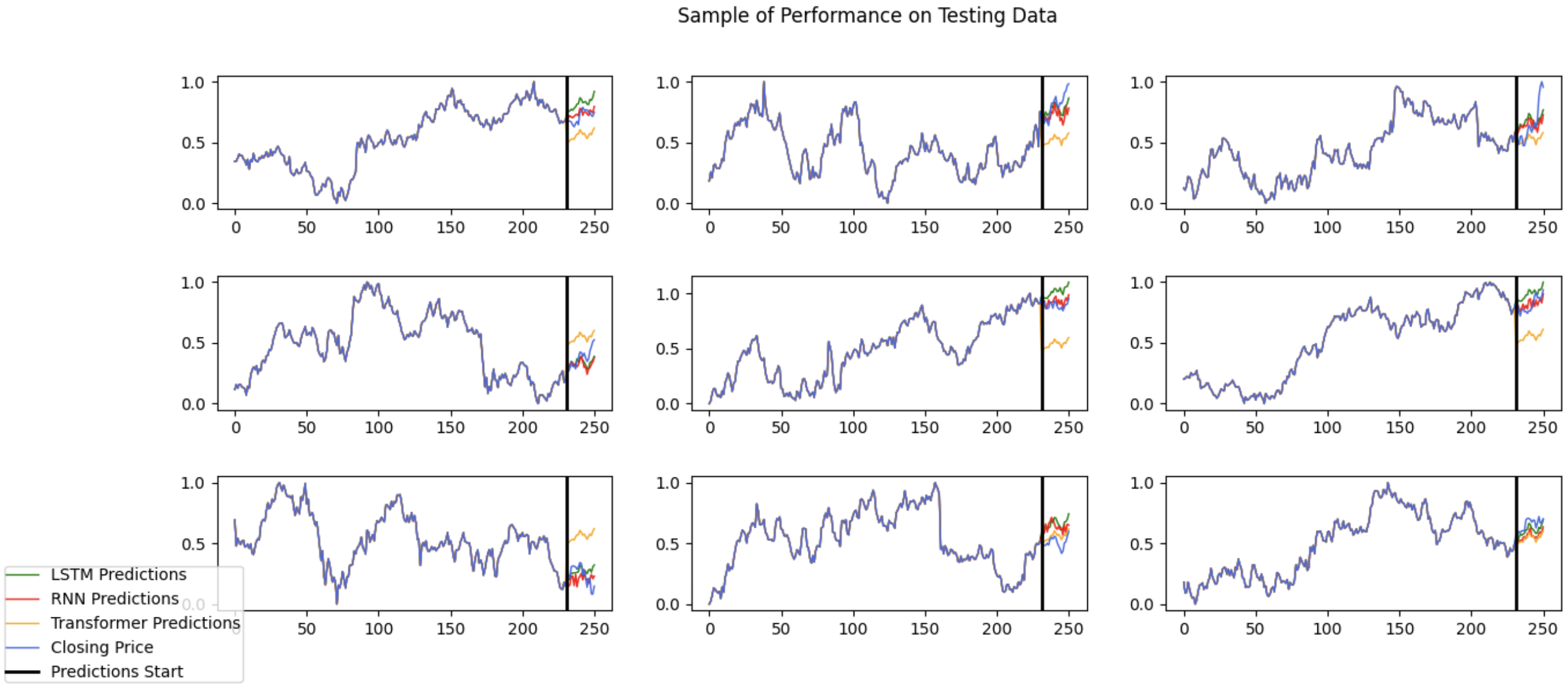

When rerunning the training, the tabular results match the visualizations. Surprisingly, Transformers perform worse than RNNs/LSTMs, with less memory used but no real difference in training time. Even with adding complexity to the Transformer model via increasing the feed-forward network complexity through increasing the size of the embedded feed forward network and increasing the number of attention layers, no performance difference was seen – the time to train just substantially increased.

| Model | RMSE | Memory in Training (KB) | Time to Train (s) | Parameters (#) | Memory for Parameters (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.125 | 8233179 | 128.25 | 54190 | 211.68 |

| RNN | 0.121 | 4147757 | 87.58 | 16750 | 65.43 |

| Transformers | 0.281 | 3148379 | 87.38 | 2019 | 7.89 |

| Complicated Transformers | 0.282 | 40052260 | 1243.01 | 16248 | 63.47 |

This seems to go against prior results which almost universally found Transformers faster without sacrificing efficiency

I did this by predicting the closing price of just one day of data using a week of prior data. I normalized all data and retrained my models. I reverted back to the simple transformer model in an effort to test relatively equivalent model complexities.

| Model | RMSE | Memory in Training (KB) | Time to Train (s) | Parameters (#) | Memory for Parameters (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.386 | 9588885 | 19.00 | 53221 | 207.89 |

| RNN | 0.381 | 4197690 | 13.45 | 15781 | 61.64 |

| Transformers | 0.384 | 2707340 | 11.45 | 1050 | 4.1 |

As the results show, my hypothesis was correct. The transformer performed much faster without a reduction in accuracy. However, it is also very possible that I didn’t see a time difference because I am using small models with a short training time. These timing differences could become larger with more computationally intensive models.

ECG Model Comparisons

While the results from the stock dataset were interesting, I also wanted to test these models with a different type of input that perhaps would capture different underlying strengths and weaknesses of the models. I decided to use an ECG to predict the presence of an abnormality in the heart beat. This represents a difference in the stock dataset in three key ways:

1) The output is binary instead of discrete. 2) There is a better source of ground truth for this data. If there was a definitive way to predict the behavior of a stock, everyone would be rich, but that’s not the case – there’s inherently uncertainty and an expected level of innaccuracy. For health data, the person will have the condition or not and an experienced cardiologist would be able to definitively diagnose the patient. 3) The input has an expected, structured shape. All ECGs are supposed to look roughly the same and should have a similar visibility in the dataset. This has effects on the causality window used in models that I was interested in analyzing.

I first visualized my data for both the abnormal and normal heart beats. The overall sample size was around 9000 patients, and I artificially created a 50/50 split between abnormal and normal to prevent class imbalance. I once again used an 80/20 train/test split for my models.

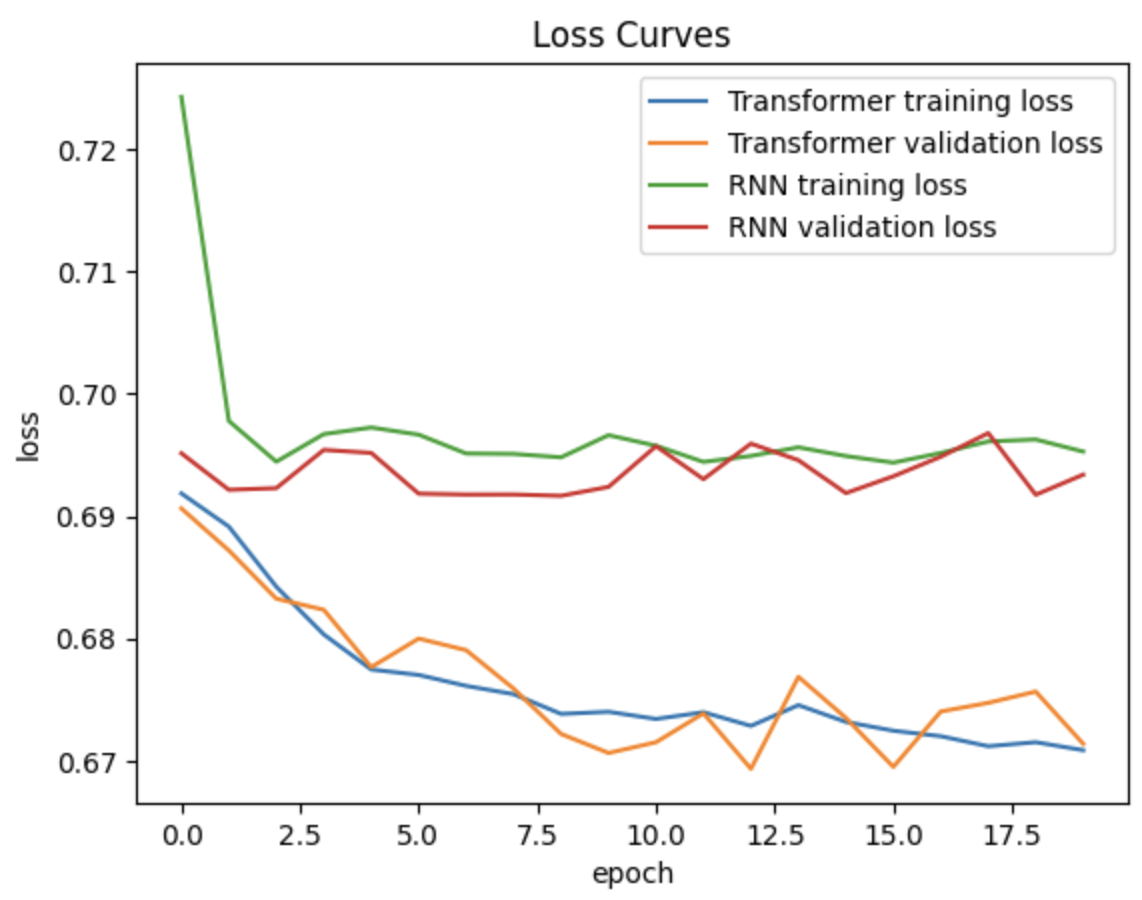

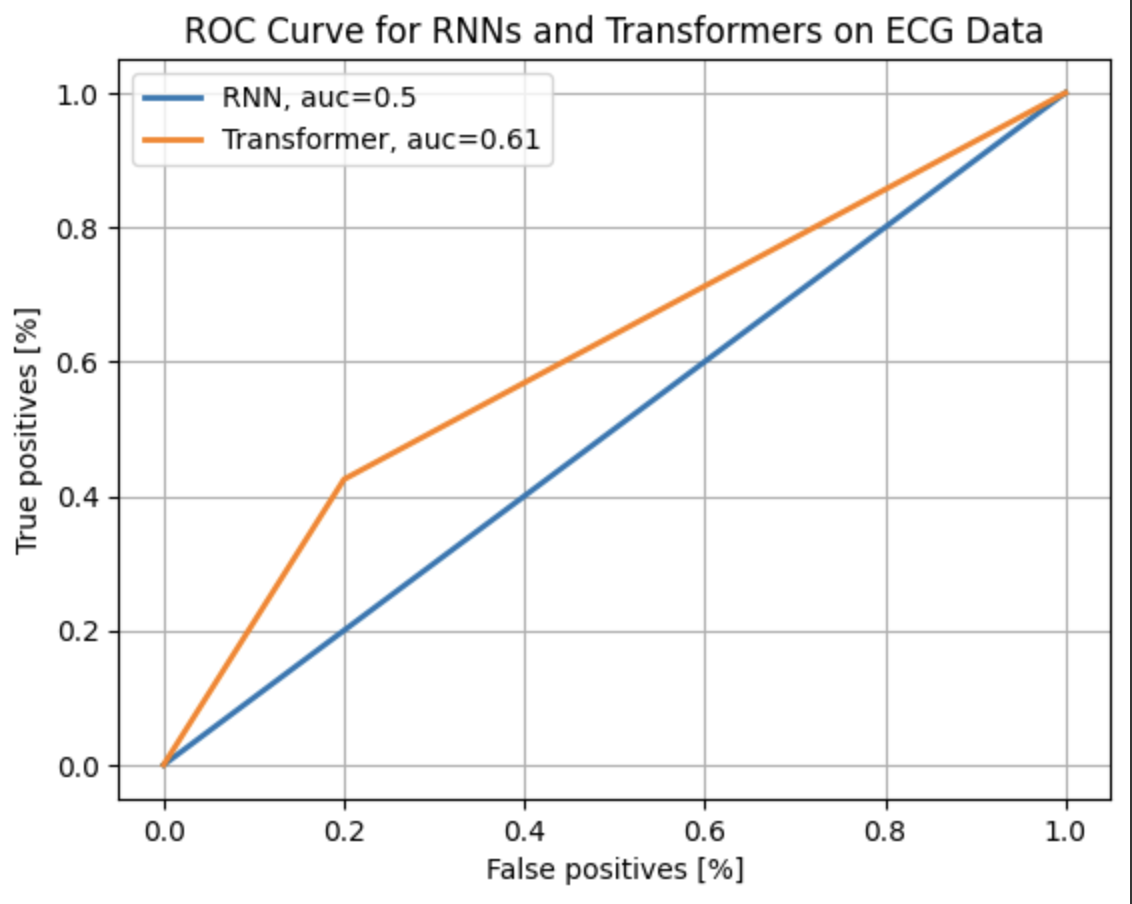

I immediately ran into difficulties once I began training with the performance of all models really being a coin toss between the two. I then focused my time on trying to build more complex models. For the RNN, I added more layers with varying dimensions and played around with adding dropout and linear layers. For the Transformer, I built up the feedforward network part of the algorithm by increasing the size of the embedded feed forward network and adding multiple attention layers. For both, I tuned hyperparameters such as the optimizer, batch size, and number of epochs. Despite this results still remined poor.

There is virutally no reduction on validation loss for the RNN graph, no matter what structure I chose. While there is a normal looking curve for transformer, the scale of loss reduction is very small when you consider the y-axis. Additionally, the RNN network never performed better than randomly, whereas the Transformer network was only slightly improved.

One interpretation of these results could be that the Transformer model performed better. However, because neither of these architectures perfomred overly sucessfully, I don’t think that is a sound conclusion. It is unclear to me if this is a shortcoming of my code or a difficulty with the problem and dataset. This would be an area where future work is required.

My main takeaway from this process of working with the ECG data was how much easier it was to tune and problemsolve with the Transformer than the RNN. For the Transformer, I was able to adjust the number of heads or the sizes of heads, or the feed foward network, etc, whereas, in the RNN, I really could only play with the layers of the RNN itself. While both of these architectures have black-box components, I found the Transformer a lot easier to work and play around with as a developer, and I could develop some intuition on what things I should change and why. This perhaps represents another difference from the transformer vs RNN debate but from a usability standpoint.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this project. First, I only analyzed a couple of different datasets. This is not representative of all of the different applications of GNNs and transformers, meaning the conclusions are limited to the datasets chosen and are not necessarily representative of the full field. Additionally, my implementation of the models may not be the most efficient ones. While I tried to test a wide range of parameters, due to limited resources available (ie time and being one person) there are undoubtably more optimal structures or hyperparameters that I did not test. This ability to not only test a limited number of parameters, but also architectures remains an overall limitation and challenge of the deep learning field

Additionally, I did not test every metric of success. While I focused on number of trainable parameters, training time, memory, and accuracy – these are not the only things that matter in machine learning. For instance, in some applications, senstivity might matter a lot more than specificity and overall accuracy. In others, explainability of the model may be essential, such as time sensitive healthcare settings

Conclusions

Transformers seem to be easier to work with when there are still questions surrounding the data. For instance, with the stock dataset, there may be circumstances where you would prefer a model that can perform well prior without normalizing the dataset if for instance, you care about the magnitude of closing prices between stocks. Similarly, for the ECG model, they were easier to tune with different hyper paramters and felt more intuitive in comparison to working with the RNN. Transformers also consistently used less memory with much fewer parameters across the board, which is important when working in resource-limited systems.

However, this project found that transformers are not always faster or more accurate than alternatives. While Liu et al found that typical transformers can find shortcuts to learn automata

These findings underscore the importance of taking the time to test different architectures in your resarch and not assuming that just because Transformers are more popular, it doesn’t mean they are necessarily the best fit for your problem. In deep learning research, we often get bogged down in tuning a model and it’s important to take a step back and consider your assumptions about the task – which may include the broader model consideration.