Understanding Linear Mode Connectivity

We study the pruning behavior of vision transformers (ViTs), and possible relations to linear mode connectivity. Frankle et al. (2022) showed that linear mode connectivity, the tendency of a neural network to optimize to the same linearly connected minimum when trained SGD noise, is strongly tied to the existence of "lottery networks," sparse networks that can be trained to full accuracy. We found that when initialized from a pretrained network, the ViT model showed linear mode connectivity when fine tuning on CIFAR-10. Conversely, random initialization resulted in instability during training and a lack of linear mode connectivity. We also found that using the PLATON algorithm (Zhang et al.) to generate a mask was effective for pruning the network, suggesting the existence of lottery ticket networks in ViTs, but the connection between the existence of these trainable subnetworks and linear mode connectivity remains unclear.

Instability Analysis and Linear Mode Connectivity

The advent of transformer models stands as a pivotal advancement within the domain of machine learning, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of artificial intelligence. First introduced in 2017 through the seminal work “Attention is All You Need” by Vaswani et al., transformers have since exploded in both uses and applications, such as language and vision tasks. In fact, ChatGPT, which was the fastest-growing application in history (until Threads in 2023), is built using a transformer architecture. Although transformers can achieve state-of-the-art performance in many tasks, they are often limited by their size, which can create issues for memory and energy both during training and deployment. For example, GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters, and GPT-4, which was released earlier in 2023, has 1.76 trillion parameters! Compression techniques such as knowledge distillation and pruning can be used to deal with these issues, reducing the size of the network while retaining most of its capabilities. Several methods already exist for shrinking transformers such as weight pruning (Zhang et al. 2022), as well as post-training compression (Kwon et al. 2022). However, there is little research on the conditions under which a transformer can be effectively compressed or at what point during training a transformer compression should begin.

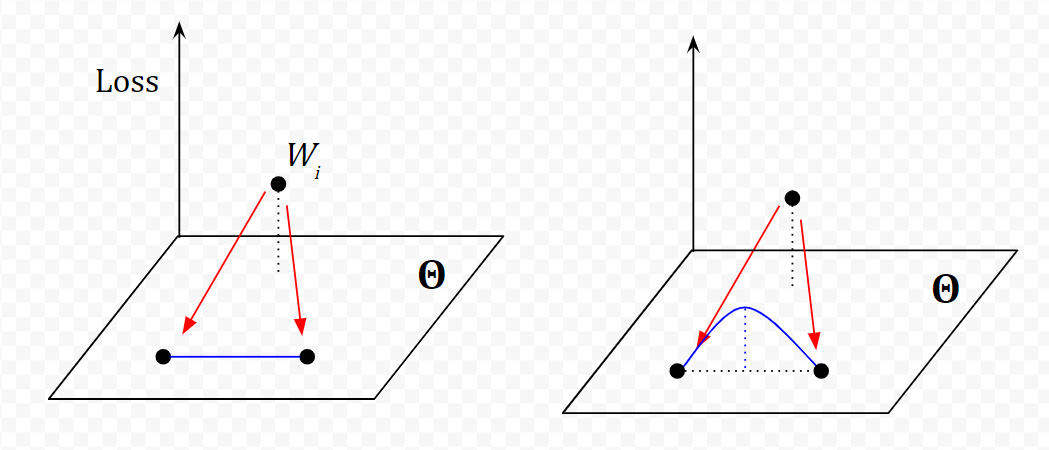

Frankle et al. (2020) suggest that instability analysis—analyzing the stability of training with respect to stochastic gradient descent (SGD) noise—could be a way of identifying conditions under which pruning can be useful. To determine whether the outcome of training is stable w.r.t SGD noise, we create two copies of a network with the same initialization, and optimize those networks using different samples of SGD noise. We can then evaluate how similar or dissimilar the resulting networks are. For this purpose, Frankle et al. propose linear interpolation instability, defined to be the maximum increase in error along the linear path in parameter space connecting the two resulting networks. When error is nonincreasing along this path, the networks are said to have linear mode connectivity. In their paper, they propose that this instability analysis is related to lottery ticket networks, which are subnetworks from randomly-initialized dense neural networks that can achieve comparable test accuracy to the original network after training. They found that pruned networks that were capable of achieving near full test accuracy were stable to SGD noise, and showed linear mode connectivity.

Frankle et al. study linear mode connectivity in neural networks, which is a stricter version of mode connectivity. They train two networks with the same initialization on SGD noise (randomly augmented datasets) and calculate the maximum loss along the linear path between the two resulting network to quantitatively analyze the instability of the original network to noise.

In our project, we plan to expand on the research from Frankle et al. and apply it to transformers. In doing so, we hope to study the conditions under which transformers can be effectively compressed as well as the optimization landscape of training transformers. We seek to evaluate linear mode connectivity in transformer architectures and whether it is an effective indicator for how effectively a transformer can be compressed.

Transformers and Related Work

We restricted our analysis of transformer architectures to the Vision Transformer (ViT) model proposed by Dosovitskiy (2021). ViT works by splitting an image into patches, then computing embeddings of those patches via linear transformation. After adding positional embeddings, the resulting embeddings are fed into a standard Transformer encoder. Due to runtime issues, we were unable to fully train transformers from scratch. We ended up working with and fine-tuning pretrained transformers, which were imported from the HuggingFace transformers package.

Shen et al. (2023) investigated a more general form of the lottery ticket hypothesis with ViTs, proposing ways to select a subset of the input image patches on which the ViT can be trained to similar accuracy as with the full data. However, they write “the conventional winning ticket [i.e. subnetwork] is hard to find at the weight level of ViTs by existing methods.”

Chen et al. (2020) investigated the lottery ticket hypothesis for pre-trained BERT networks, and did indeed find subnetworks at varying levels of sparsity capable of matching the full accuracy. Our work hoped to find similar results for vision transformers.

Linear mode connectivity is also deeply connected to the nature of the optimization landscape. This has important applications with regards to federated learning, and combining the results of independent models. For example, Adilova et al. (2023) showed that many deep networks have layer-wise linearly connected minima in the optimization landscape, which they explain as being the result of the layer-wise optimization landscape being convex, even if the whole optimization landscape is not. They found similar behavior in vision networks trained on CIFAR-10.

In our project, we seek to evaluate the connection between linear mode connectivity and the existence of winning subnetworks. We expand on the work from Shen et al. and Chen et al. by incorporating the linear mode connectivity analysis proposed by Frankle et al. as well as search for conventional winning subnetworks in transformers for vision tasks. Our goal is to find conditions and methods for which transformers can be compressed while retaining high performance.

Experiments with Linear Mode Connectivity

We decided to work with the pretrained ViT model from HuggingFace transformers, and to fine tune this model on CIFAR-10. We also augmented the data set of 32x32 images with a random 24x24 crop followed by resizing, followed by a random horizontal flip and color jitter (randomly changing brightness, contrast, saturation and hue). To evaluate linear mode connectivity, we train a pair of models with the same initialization on different randomly shuffled and augmented datasets.

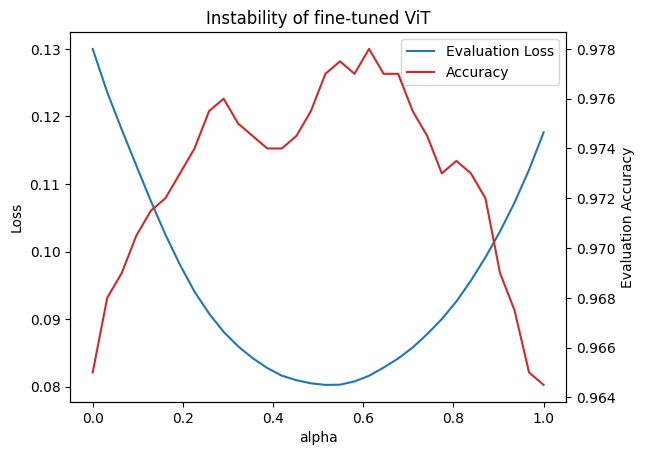

In order to assess the instability of the original network to the dataset augmentations, we use the procedure described by Frankle et al. and evaluate the test loss and accuracy of the linearly interpolated models. The weights of the interpolated models are directly calculated from the weights of the trained models using evenly spaced values of \(\alpha\). The test dataset did not receive the augmentations that the training dataset did.

All models trained for the linear interpolation instability analysis were trained using the AdamW optimizer for 8 epochs with a learning rate of 2e-4. We use the default ViTImageProcessor imported from HuggingFace to convert the images into input tensors.

The above plot shows the result of linear interpolation after fine tuning two copies of the pretrained model. The evaluation loss is non-increasing, and in fact decreases, possibly as an artifact of the fact that the test set did not recieve augmentations. Otherwise, it seems that there is linear mode connectivity, at least in the local optimization landscape when starting from a pretrained model.

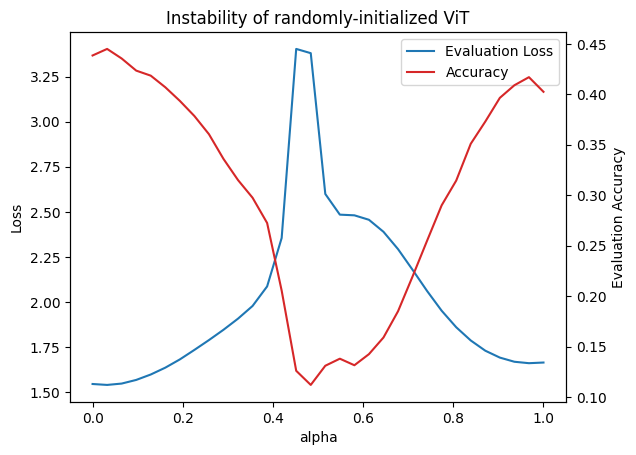

However, we failed to observe linear mode connectivity in randomly initialized transformers, noting an increase in test loss as well as a decrease in test accuracy around \(\alpha = 0.5\). The maximum observed test loss of the interpolated models is more than double the mean of the test losses of the original pair of trained models, which is much more than the threshold of a \(2\%\) increase used by the original authors.

The resulting networks seem to end up in disconnected local optima, implying that these networks are not invariant to the dataset augmentations. This is consistent with the analysis done by Frankle et al., who find that the stability of networks increases over the course of training.

Our results combined with the original analysis by Frankle et al. seems to suggest that linear mode connectivity emerges at some point during training, but we have yet to observe the point at which it emerges due to computation restraints and the size of the ImageNet dataset used to pretrain the ViT models.

Pruning

We used the PLATON compression algorithm (Zhang et al. 2022) during training to prune networks to different levels of sparsity. PLATON uses several “scores” to prune parameters. One score is parameter magnitude; smaller magnitude parameters tend to be pruned. However, in a complex network, small magnitude weights can still have a large impact; to measure this, PLATON uses the gradient-weight product \(\theta^T \nabla \mathcal{L}(\theta)\) as a first order Taylor approximation of the impact of the removal of a weight on the loss. PLATON also maintains uncertainties for all the weights, preferring not to prune weights with uncertain scores.

Pruning and retraining the pretrained model to 20% of its original size over 4 epochs results in a test accuracy of 95.3%, compared to 98% accuracy of the full model, and pruning to 5% resulted in 93.7% test accuracy. So although the compressed models cannot reach the accuracy of the original model, they are able to still maintain a relatively high test accuracy, and the PLATON algorithm does a good job of selecting weights. We also used the pruned weights at 20% sparsity to generate a mask, and applied this mask to the original model.

When training the original model, but applying a mask (effectively setting the corresponding weights and gradients to zero), we were able to train the model to 93.6% test accuracy. This supports the lottery ticket hypothesis, since the PLATON algorithm can be used to identify a relatively small subset of weights from the pretrained network that can be trained high accuracy in isolation.

Analysis and Conclusions

Our results with linear mode connectivity suggest that at some point during the training process, optimization ends up in a linearly connected local minimum, and further optimization will be stable to SGD noise. This is because we were indeed able to observe linear mode connectivity when fine tuning a pretrained mode. Additionally, with random initialization, we found the absence of linear mode connectivity. Unfortunately, we were not able to determine exactly where in the training process linear mode connectivity emerges.

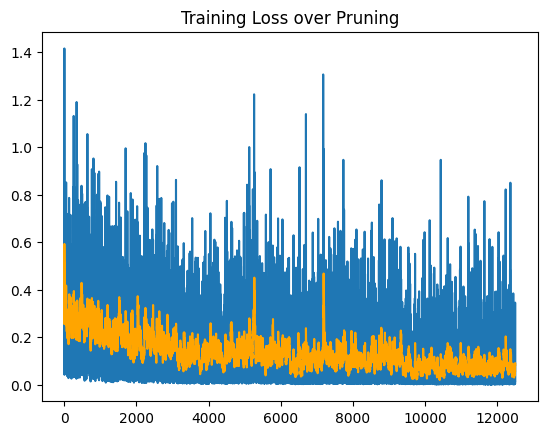

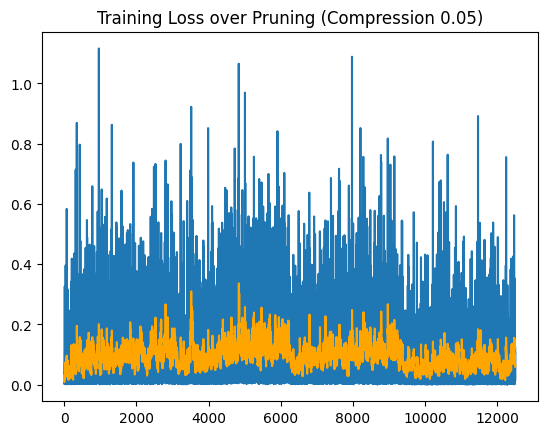

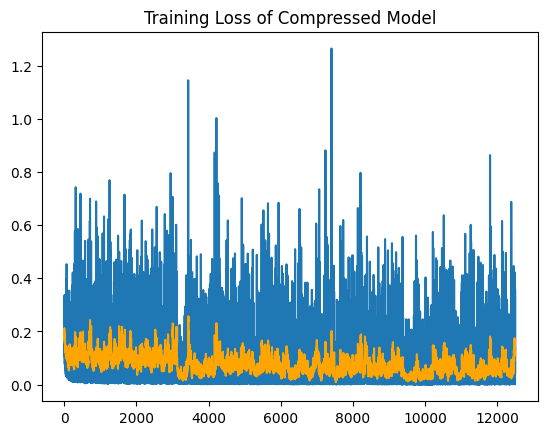

It is notable that over the course of training, the loss does not seem to go down steadily, rather rapidly oscillating between high and low loss. The exponential moving average smooths it out, but it is still quite chaotic. During pruning, it seems plausible that the oscillations could correspond to weights being pruned, but the model approaches the target ratio of nonzero weights by the end of the third epoch of training, leaving the behavior in the final epoch unexplained. Furthermore, the training loss displays similar behavior while training the masked models. Further work could be done to investigate this phenomena and potentially make pruning/training more stable.

Our results with pruning show that a standard compression algorithm, PLATON, is able to sucessfully prune the pretrained ViT model to high levels of sparsity while maintaining relatively high accuracy. Our results with masking weights also suggest the existence of lottery ticket networks in the pretrained model, since we were able to train the corresponding subnetwork to a high level of accuracy. Unfortunately, the connection between linear mode connectivity and lottery ticket transforms remains very ambiguous, since we were unable to perform pruning experiments on models that did not demonstrate linear mode connectivity.

Further work could be done to investigate linear mode connectivity from different levels of pretraining as initialization, which would shed light on when the optimization of transformers settles into a connected minimum (or when it doesn’t). Further work on when linear mode connectivity arises, as well as experiments pruning the corresponding networks, would help determine if there is a connection between connectivity and the presence of lottery transformers. This would also be important for determining whether linear mode connectivity is a good indicator that transformers can be compressed more definitively. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, the existence of lottery networks in language models has already been investigated, and it would be interesting to see if this is related to linear mode connectivity as well.

References

Adilova, L., Andriushchenko, M., Kamp, M., Fischer, A., & Jaggi, M. (2023). Layer-wise Linear Mode Connectivity.

Frankle, J., Dziugaite, G. K., Roy, D. M., & Carbin, M. (2020). Linear Mode Connectivity and the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis.

Zhang, Q., Zuo, S., Liang, C., Bukharin, A., He, P., Chen, W., & Zhao, T. (2022). PLATON: Pruning Large Transformer Models with Upper Confidence Bound of Weight Importance. In K. Chaudhuri, S. Jegelka, L. Song, C. Szepesvari, G. Niu, & S. Sabato (Eds.), Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (Vol. 162, pp. 26809–26823). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v162/zhang22ao.html

Kwon, W., Kim, S., Mahoney, M. W., Hassoun, J., Keutzer, K., & Gholami, A. (2022). A fast post-training pruning framework for transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 24101–24116.

Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S., Uszkoreit, J., & Houlsby, N. (2021). An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale.

Shen, X., Kong, Z., Qin, M., Dong, P., Yuan, G., Meng, X., Tang, H., Ma, X., & Wang, Y. (2023). Data Level Lottery Ticket Hypothesis for Vision Transformers.

Chen, T., Frankle, J., Chang, S., Liu, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., & Carbin, M. (2020). The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis for Pre-trained BERT Networks.