Investigating Vision Transformer-Based Models for Closure Modeling of Fluid Dynamical Systems

Project Report for 6.s898 Deep Learning (Fall 2023)

Motivation and Background

Over the past decade, deep learning models have increasingly been used for modeling time series data for fluid dynamical systems. One of the most recent applications is in forecasting weather

Training deep neural models to completely replace numerical solvers requires a lot of data, which might not be available due to constraints with sensor and satellite usage associated with collecting ocean and weather data. Additionally, these surrogate models are completely data-driven and could lead to non-physical predictions (lack of volume preservation, and non-conservation of physical laws) if these needs are not explicitly attended to during training

In closure modeling, we are interested in solving the following problem: Here, we describe the case of closure modeling with loss of accuracy due to low numerical resolution which leads to loss of sub-grid scale processes, and sometimes even truncation and discretization errors. But there could also be closure due to missing or unknown physics, incorrect parameters, etc.

Consider a low-fidelity model (low resolution):

and the high fidelity (high resolution) equivalent model:

The purpose of the closure in this context is to augment the low fidelity model with a neural closure model $NN(u_{LF}(t))$, such that:

Previous works for neural closure models have used neural ODEs and neural DDEs

Another issue with using neural networks for solving fluid dynamics PDEs is unstable recursive predictions, due to the exponential growth of accumulated errors across time. Some papers have explored ways to limit this exponential error growth by using custom loss functions

Methods and Experiments

Test case setup

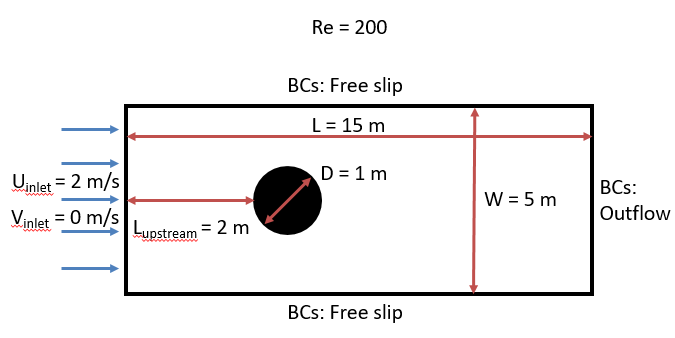

In this project, we develop and investigate methods to augment low-fidelity (low-resolution) numerical simulations of flow past a cylinder with deep neural networks and compare them with high-fidelity (high-resolution) numerical simulations. The neural closure aims to learn the missing subgrid-scale processes and truncation and discretization errors in the low-fidelity simulation and augment it to match the high-fidelity simulation

Data generation

We use data generated from numerical simulations for two-dimensional flow past a cylinder

To generate the high-fidelity (high-resolution) data we use a resolution of 200x600. For the low-fidelity (low-resolution) data, we use a resolution of 50x150. The MIT-MSEAS 2.29 numerical simulation uses second-order finite volumes and a time-step of 0.000625s. The diffusion operator was discretized using central boundary fluxes. For advection, we use a total variation diminishing (TVD) scheme with a monotonized central (MC) symmetric flux limiter. For numerical time integration, we use a rotational incremental pressure correction scheme. The reader is directed to

Data usage for deep learning

We save the u and v velocity fields, as well as the time derivatives (which act as the numerical approximation of the RHS terms (dynamics terms) of the PDEs being solved).

Thus we save a tensor of size $9600 \times 4 \times \text{num. horizontal cells} \times \text{num. vertical cells} $, for each numerical resolution, where 9600 is the total number of time steps saved, and 4 indicates 4 channels for the 2 velocities and 2 time derivatives (horizontal: u and vertical: v). To maintain the same grid size for deep learning, we down-sample the high-fidelity data using linear interpolation to have the same size as the low-fidelity data.

For deep learning, we neglect the first 4800 snapshots as spin-ups to reach a fully developed flow state. Then we use the next 3600 snapshots for training, 600 snapshots for validation, and 600 snapshots for testing.

We created a custom data class with a data loader to feed randomized sequences of required sequence lengths from the training set for training. For inference, we feed the snapshots one by one from the test data set.

Deep learning model

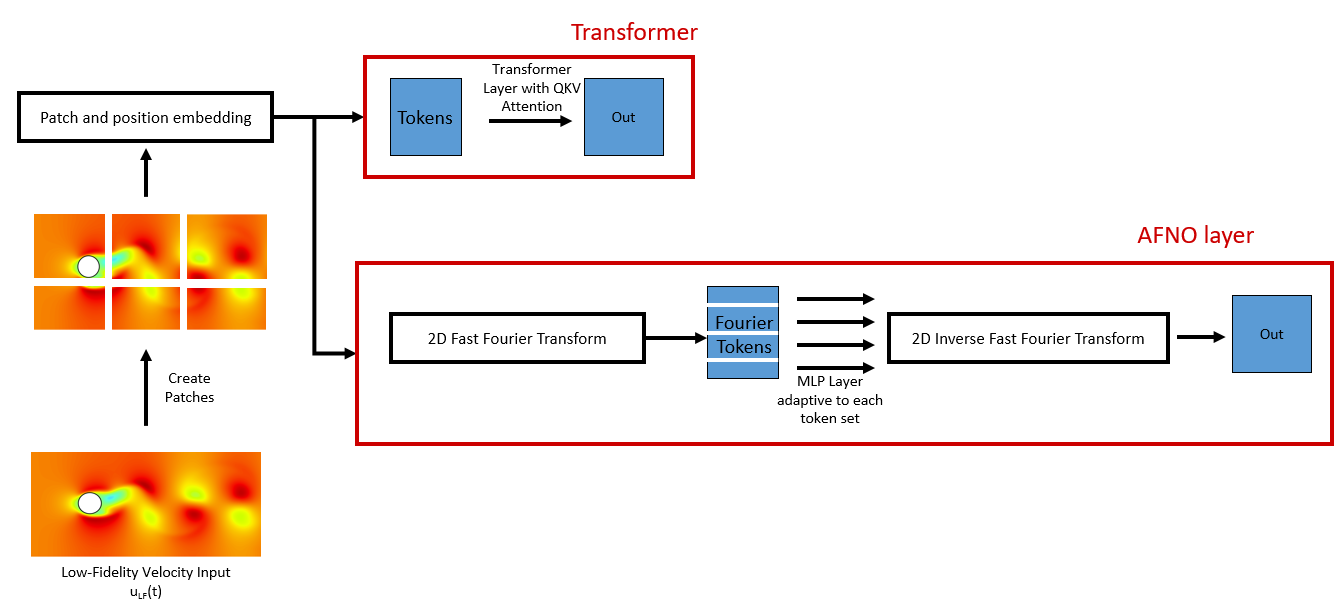

For this project, we initially tried to explore architectures inspired by Fourier neural operators

Instead, we focus on utilizing vision transformer-based architectures for our closure modeling task. Although they have a higher number of parameters than AFNO, vision transformers rely on self-attention that can learn long-range physical dependencies, and are hence well suited to our task.

Single time-step predictions

We first focus on a framework that just predicts output for the next time step, i.e., single time-step predictions. This is a simpler task than recursive or long roll-out predictions which we will discuss in the following sections.

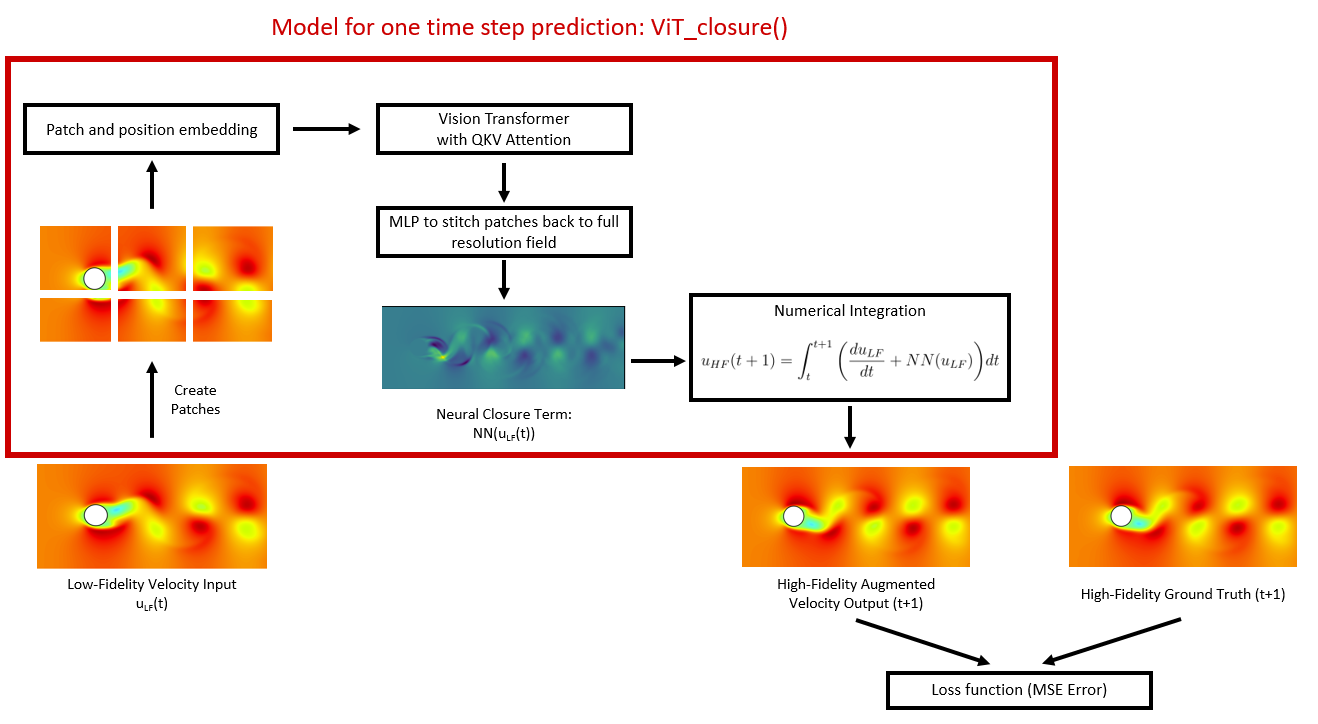

Figure 3 contains a flowchart of how our Vision Transformer-based closure model “ViTClosure()” works. In the first part of the architecture, a vision transformer-based architecture takes in a low fidelity velocity field at time t as input and returns the closure term (which is similar to a time derivative field) at time t+1.

- First, a 2D CNN transforms the input low fidelity 2D velocity field at time $t$ into patches

- Next, a layer adds positional embedding and creates tokens. In this project, we use learned absolute positional embeddings.

- Next, the tokens are passed through a vision transformer with many attention layers with multi-headed attention heads.

- Next, we have a layer that applies layer norm to the final output of the vision transformer. Here the output would be of size $\text{Batch size} \times \text{Num. of tokens} \times \text{Hidden dimension}$. Since we need an output field of the same dimension as the input field, we use an MLP for this transformation. We call this output closure term $NN(u_{LF}(t))$.

- Next comes a numerical integration step which combines the low fidelity numerical solver (which provides $\frac{d u_{LF}}{dt}$) with the neural closure term $NN(u_{LF}(t))$, to predict the high-fidelity field $u_{HF}(t+1)$, shown in Eq. (4).

Loss functions

Finally, we compare the predicted high-fidelity field $u_{HF}(t+1)$ and neural closure term $NN(u_{LF}(t))$ with the ground truth simulations. Similar loss functions have been used in neural closure models based on neural-ODEs

Then, we use backpropagation with the Adam optimizer and a cosine learning rate to optimize the model parameters.

Fine tuning for recursive predictions

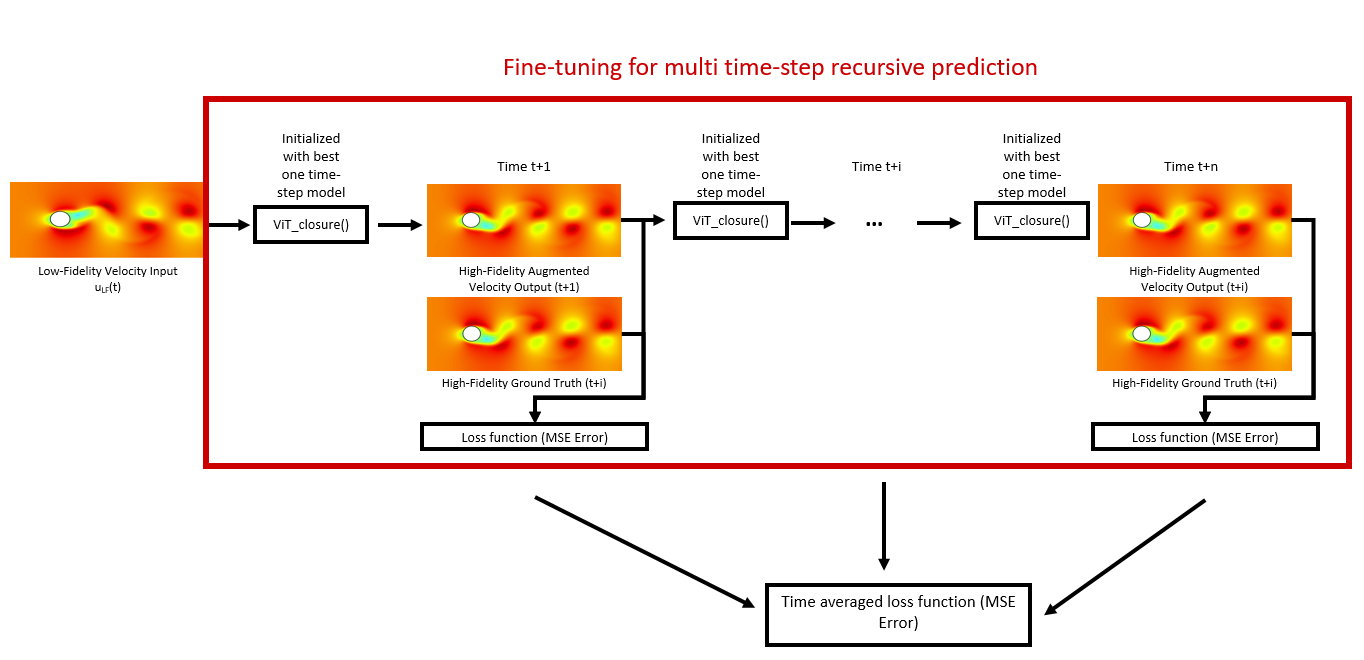

Now that we have a model trained for single time-step predictions, we move on to multiple time-step predictions or long roll-out predictions. Achieving long roll-out predictions is hard due to the exponential accumulation of errors during recursive predictions. Hence a small error at timestep t+1 could lead to huge errors after a few more timesteps.

- We first initialize the model using the best-performing model of the single-time step prediction, i.e., the best ViT-closure() model.

- Next, we recursively use the ViT-closure() model, and feed the output at time t+i as input to the model at time t+i+1.

- Finally, we average all the losses across time Eq. (6). and backpropagate through time.

where ‘n’ is a hyperparameter that determines how many times the model is propagated recursively during fine-tuning.

Results and Analysis

We ran many experiments for the flow past a cylinder set-up with high-fidelity (high-resolution) data of resolution 200x600 and low-fidelity (low-resolution) data of resolution 50x150. The high-fidelity run was downsampled as described previously to achieve the same grid size as the low-fidelity data for comparison. We used one NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU for all the training and inference runs.

Single time-step predictions

First, we train the single time-step prediction model using the procedure described previously. We tried many runs (~ 20) by varying the key hyperparameters such as the global batch size between 1 and 16, the embedding dimension between 64 and 256, the number of attention layers between 3 and 9, the number of attention heads between 5 and 10, the patch size between 5 and 10, and the weightage in the loss function $\lambda$ between 0 and 1.

Increasing the batch size led to faster training, but higher GPU memory requirements. With a batch size of 1, it took around 8 minutes of wall-clock time for one epoch of training. We observed the best training results with a loss function weightage $\lambda$ of close to 0, this may be because we ran the numerical solver offline to obtain the low-fidelity derivatives and ground truth closure, which is not as accurate as obtaining these values online during training. The other hyperparameters decreased training errors but the validation error after 50 epochs of training was around 0.03 m/s compared to the average velocity field of 2 m/s (so about 1.5\% relative error). Regularization and avoiding overfitting of the model needs to be investigated further in future work.

For the GIFs below, we use the best-trained model, which was trained using a batch size of 16, embedding dimension of 128, number of attention layers of 6, number of attention heads of 10, patch size of 5, and weightage in the loss function $\lambda$ of 0.05.

Using this model, we can visualize the attention layers, to identify which features have been most useful for closure modeling. Figure 5 shows the attention map of multiple patches on the low-fidelity u velocity input at the same time step. We can observe that the most important feature seems to be the phase (whether the eddy is facing upward or downward) of the eddy shed right at the cylinder, and the other eddies downstream. We can also see that there is very little attention near the inlet and top and bottom boundaries since those values are set as inputs to the simulation.

Figure 6 shows the attention map of a single patch on the low-fidelity u velocity input at different time steps. We can again observe that the attention map follows the eddy shedding at all times. These two plots indicate that the model can identify that the eddies are the most important features, and the inlet and boundaries are not that critical for predicting the flow field. However, this may not be true if we are attempting to do closure modeling between simulations with different inlet and boundary conditions, which can be further investigated in future work.

Now that we know that our model focuses on the most important features for closure modeling, we can compare the field plots of the high-fidelity predictions using the model.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the comparison of the neural closure model predictions, and predictions with just low-resolution simulations. We can observe that the neural closure model prediction (3rd row) performs way better than the low-fidelity simulations (2nd row). The low-fidelity simulation is out of phase compared to the high-resolution ground truth, but our neural closure model is able to augment the low-fidelity simulation and learn the true phase and missing sub-grid scale processes!

Fine tuning for recursive predictions

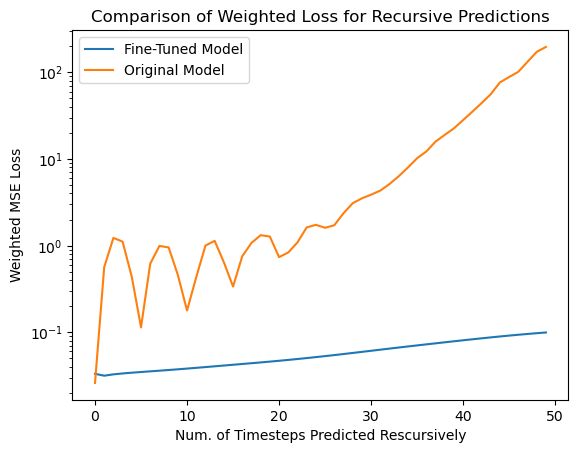

Next, we evaluate the capabilities of the best model from the single time-step predictions for recursive predictions. We set the initial conditions to be the first snapshot in the testing data set and perform recursive predictions as described before for 50 time steps. The resulting predictions and error fields are shown in the GIF in Figure 9. We can see that the errors grow exponentially even before a few recursive predictions, and the model is incapable of any accurate long-term predictions. The predictions quickly become out of phase compared to the ground truth.

Next, we initialize a new model using the weights from the best single time-step predictions and perform fine-tuning as described previously.

We explore multiple values of $n$, which is a hyperparameter that controls how long the recursive sequence lengths used for fine-tuning are. We found the ideal value of ‘n’ to be $5$ timesteps. Using $n<5$ led to inaccurate recursive predictions, using $n>5$ did not lead to much improvement in accuracy but increased training costs due to requirements to backpropagate through long-time sequences.

The resulting predictions and error fields after fine-tuning are shown in the GIF in Figure 10. We can observe that the model predictions remain in phase with the ground truth, and the error fields are low up to 50 timesteps. We can see that even though we only fine-tuned with sequence lengths of 5, the resulting model is stable for long roll-outs of up to 50-time steps. However, this could be because eddy shedding in flow past a cylinder is somewhat periodic, which aids in some generalization.

Finally, to show the effectiveness of fine-tuning, we compare the weighted loss of the original best single-time step model and the resulting best-fine-tuned model for long roll-out predictions of 50-time steps in Figure 11. We can see that the original model sees exponential growth of errors up to 2 orders of magnitude higher in just 10 recursions while the fine-tuned model is stable up to 50 recursions. Thus, we can see that our fine tuning mechanism allows for stable roll outs well beyond the training sequence length.

Conclusions and Future Work

In this project, our key contributions have been

- Extending vision transformer-based models for neural closure modeling for an idealized 2D flow field (eddy shedding from flow past a cylinder). We observed a reduction in error fields by up to 95\% using neural closure augmentations, compared to just using the low-fidelity output.

- Developing a fine-tuning procedure to achieve long recursive predictions, i.e., we have achieved stable long roll-outs for ~50 timesteps by training on just ~5-time step sequences.

Some of the limitations of our model and future work are:

-

Scalability and usage of large amounts of VRAM for training: Training with a batch size of 1 takes up 7 GB of VRAM for the 50x150 field. Training with parallel GPUs or other more efficient transformer token mixing models like Adaptive Fourier Neural Operators (AFNOs) needs to be explored to increase the batch size or number of grid points.

-

Numerical integrator inside closure model: We use a forward Euler numerical solver for the numerical integrator during closure modeling, however more stable and accurate solvers like DOPRI5 or RK4 need to be investigated.

-

Offline training: Right now, our model uses offline data generated by a numerical solver. For complete accuracy, we would need to integrate the numerical solver (written in MATLAB or FORTRAN) into the training code and allow it to compute the low-fidelity derivatives online during training.

-

Effect of periodicity: The eddy shedding in the flow past a cylinder is somewhat periodic which may aid the deep learning model during training. The model needs to be tested on more realistic flows like gyre flow, or real ocean velocity fields, to test its true capabilities.