Activation Patching in Vision Transformers

Motivation

Neural networks contain large amounts of parameters and connections that they use to model a given phenomenon. Often, the breadth and complexity of these systems make it difficult for humans to understand the mechanisms that the model uses to perform its tasks. The model is treated like a black-box. When attempting to alter the behavior of the model when it does not behave in the desired way, engineers often rely on trial-and-error tuning of hyperparameters or providing larger, more diverse datasets for training. However, it is often difficult to get representative training data. In addtion, hyperparameters can improve training but are limited in their ability to alter the innate limitations of a model.

Mechanistic interpretability aims to unpack the underlying logic and behaviors of neural networks.

A better understanding of the logic within neural networks will allow for more strategic improvements to these models inspired by this newfound understanding. In additon, interpretability is the first step toward changing and correcting models. With an understanding of the underlying mechanisms comes more control of these mechanisms, which can be used to apply necessary changes for goal alignment and mitigating issues such as bias. Mechanistic interpretability plays a key role in ensuring the reliability and safety of AI systems.

Related Work

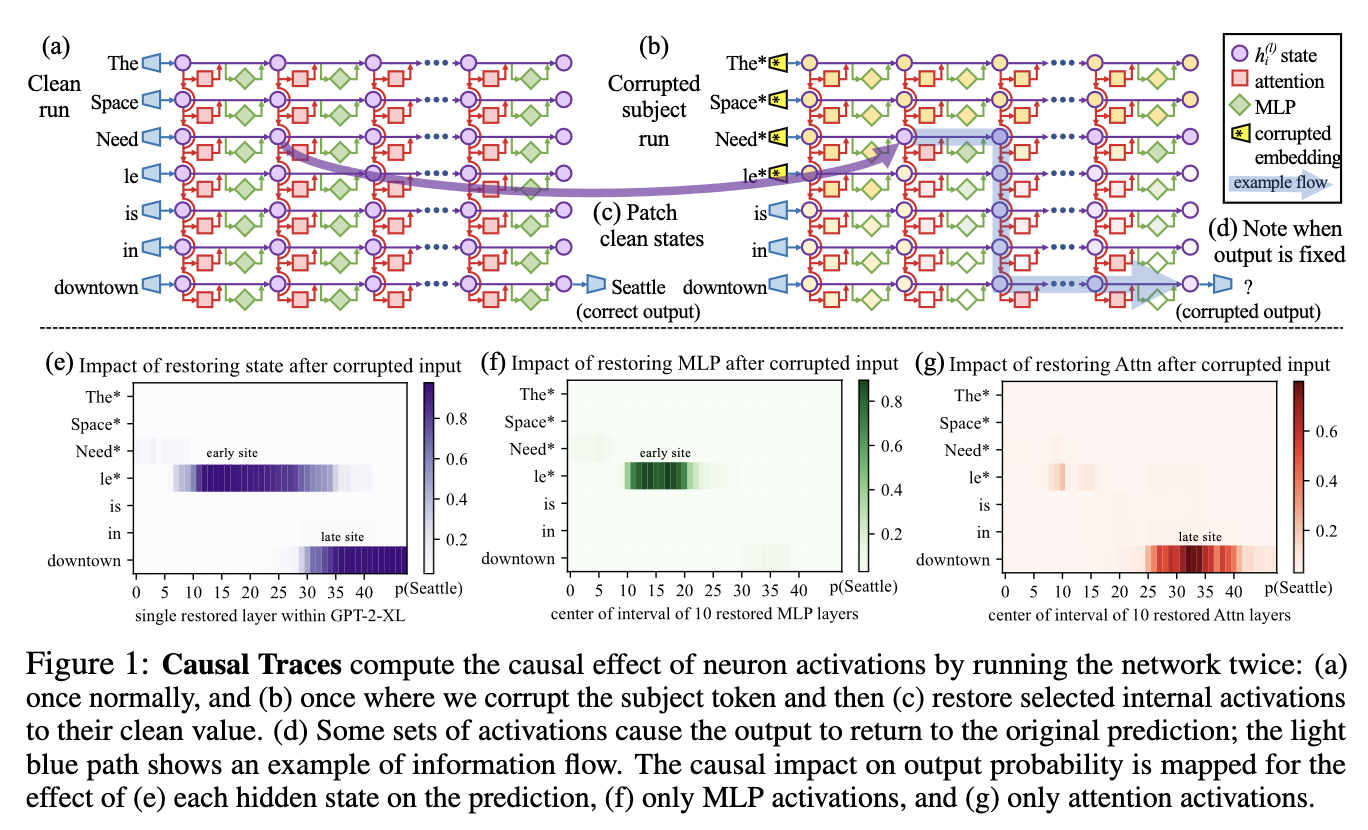

Pearl et al.

For example, if the hidden state for a given attention head in a language model with prompt “The Eiffel Tower is in” is patched into that of a prompt “The Colosseum is in” and successfully changes the output from “Rome” to “Paris”, this indicates that the patched head contains knowledge about the Eiffel Tower.

Meng et al. also provides an example of how interpretability can open opportunities for model editing.

Activation patching has been used for language models, which rely on a transformer architecture. Vision transformers

Methods

The model that was used for this investigation was a vision transformer that was fine-tuned for the CIFAR10 dataset, a dataset that is often used to train image classification models. The pretrained model that was used, which can be found here, often fails to classify images in the dataset if they are converted to grayscale. For example, the model classifies the image of a deer below as a cat.

In order to trace which attention heads focus on color information, a clean, corrupted, and restored run was performed with the model. A batch was created was a given image along with a grayscale version of that image. The colored image played the role of the clean run. The grayscale image is a corrupted input that hinders the model’s ability to classify the object in the image. This is reflected in the lower logits when the classifier attempts to classify the grayscale image. Even in the off chance the model is still able to classify the image correctly in the corrupted run, the logits will reflect the confidence, or lack thereof, of the model in its classification.

This corrupted grayscale run was the baseline in the investigation. Once this baseline was established, the restored run demonstrated the influence of a given attention head. In this run, the hidden state in a given corrupted layer was replaced with the hidden state at that layer from the clean run. A hidden state was defined as the values of the embedded tokens after passing through a given layer in the neural network. One set of restored runs only restored states for individual layers. However, as demonstrated in previous research

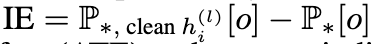

This analysis was performed for 1000 images from the CIFAR10 dataset. For each image, the output of the restored run was collected and compared to that of the corrupted run. The indirect effect of a given layer was calculated by the difference in the softmax probability of the class of the image between the corrupted and patched run.

For each image, this patching process was repeated for every attention layer in the neural network. Finally, the results of activation patching were averaged together for each layer across all of the images in order to get a general sense of which layers are most pertinent for processing image color information.

Results

When single layers were patched rather than a window of layers, results matched that of Meng et al. The patching of a single activation did not have a unique effect on the output.

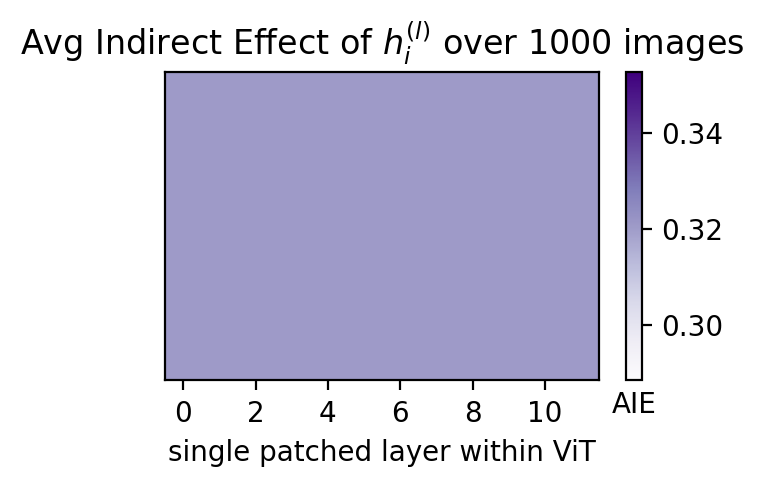

From averaging the change in outputs from activation patching 1000 CIFAR10 images, results show that attention heads of most relevance to color tended to be in the middle or last layers.

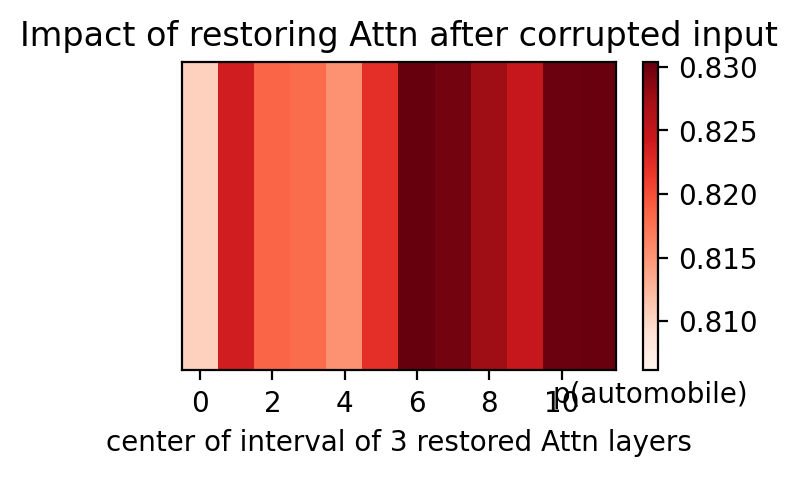

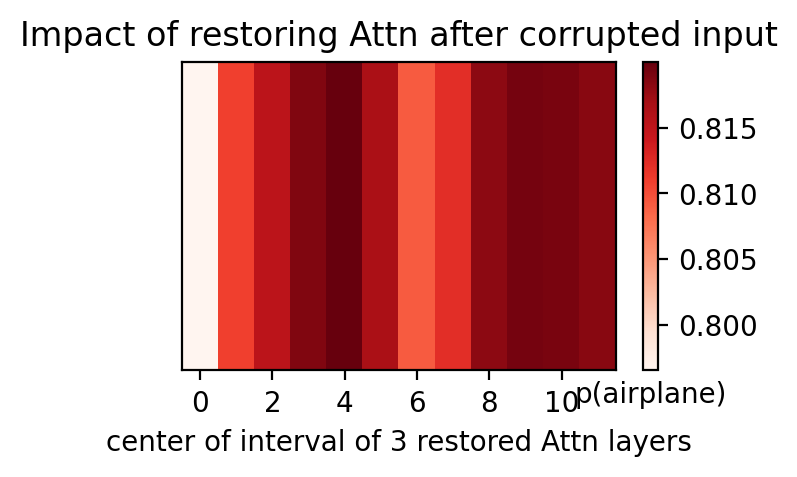

Here are some examples of activation patching for individual images from the dataset. The graphs display the probability in the output for the correct class of the given image.

This experiment found that in a 12-layer network with a window size of 3, attention in the fourth layer and final layers of the network had the biggest impact on predictions made by the model. In these layers, the probability of the correct class of the image had the largest change when clean hidden states were patched from these layers into the grayscale run of the vision transformer.

As portrayed by the tracing of individual images displayed above, not all images followed this trend exactly. The deer image, for example, had more emphasis on earlier layers and less emphasis on later layers. The automobile had a stronger influence from the attention layer 6 than that of 4. However, it was generally common for layers in the middle and end of the network to play a large role in this classification problem.

Conclusion

The influence of attention heads close to the output align with the conclusions found by Palit et al. This is likely due to direct connection of final layers to the output. There is also a significant influence of middle attention heads on the output, which is some indication of the key information that is stored in these layers relevant to color. A possible explanation is that these layers are close to the input layer, which directly stores color information, while maintaining enough distance from the input to have narrowed down (attended to) which tokens are relevant to the class the image belongs to. This study provided an initial insight into how vision transformers store information about colors of an image.

Future investigations could include other forms of corruption to provide more information about the roles of the different attention layers in a trasformer. For example, adding noise to the image embeddings would give insight to the general importance of different layers rather than just focusing on color information. By varying the amount of noise, this corruption would allow more control on how much the output would change and possibly allow room for more significant restorative effects from patching and therefore more definitive results as to where the most influential attention heads live in vision transformers. Other methods of corruption could also explore other tasks ingrained in image classification, such as blurring for edge detection or using silhouettes and image segmentation for texture or pattern identification. In addition, performing activation patching with window sizes other than 3 could provide more context as to how important is an individual attention layer. A similar experiment should be performed on other models and datasets. A focus on different objects, larger datasets, and larger networks would help verify the role of middle and final layer attention heads indicated by this study.