Transformer-Based Approaches for Hyperspectral Imagery in Remote Sensing

The introduction of transformer-based models in remote sensing signals a transformative shift in hyperspectral image (HSI) classification, providing advanced tools to navigate the complex data landscape. This investigation gauges the potential of vision transformers to accurately discern the detailed spectral and spatial correlations within HSI, accentuating their capacity to significantly improve detection and analysis in environmental monitoring and land management.

Introduction

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) captures a wide spectrum of light per pixel, providing detailed information across numerous contiguous spectral bands. Unlike multispectral imaging, which only captures a few specific bands, hyperspectral imaging offers finer spectral resolution, allowing for more precise identification and analysis of materials. This capability makes it valuable in remote sensing for applications like mineral exploration, agriculture (e.g., crop health monitoring), environmental studies, and land cover classification. Each spectral band captures unique light wavelengths, enabling the identification of specific spectral signatures associated with different materials or conditions on the Earth’s surface. HSI images present unique challenges in deep learning compared to typical RGB images due to their high dimensionality. Each pixel in a hyperspectral image contains information across hundreds of spectral bands, leading to a massive increase in the data’s complexity and volume. This makes model training more computationally intensive and can lead to issues like overfitting if not handled properly. Current datasets, such as the Indian Pines or Salinas Scenes datasets, often have fewer samples compared to standard image datasets, exacerbating the difficulty in training deep learning models without overfitting. There’s also the challenge of effectively extracting and utilizing the rich spectral information in these images, which requires specialized architectures and processing techniques. However, analysis of hyperspectral data is of great importance in many practical applications, such as land cover/use classification or change and object detection and there is momentum in the field of remote sensing to embrace deep learning.

Traditional hyperspectral image classification (HSIC) methods, based on pattern recognition and manually designed features, struggled with spectral variability. Deep learning, particularly CNNs, brought advancements by extracting intricate spectral-spatial features, enhancing HSIC’s accuracy. Yet, CNNs have their drawbacks, such as a propensity for overfitting due to the high dimensionality of hyperspectral data and limitations imposed by their fixed-size kernel, which could obscure the classification boundary and fail to capture varying spatial relationships in the data effectively.

Compared to CNNs, there is relatively little work on using vision transformers for HSI classification but they have great potential as they have been excelling at many different tasks and have great potential in the field of HSI classification. Vision transformers, inspired by the Transformer architecture initially designed for natural language processing, have gained attention for their capacity to capture intricate patterns and relationships in data. This architecture leverages self-attention mechanisms, allowing it to model long-range dependencies effectively, which can be particularly advantageous in hyperspectral data where spatial-spectral interactions are crucial. Spectral signatures play a pivotal role in HSI analysis, enabling the differentiation of materials or conditions based on their distinct spectral characteristics, a capability that conventional RGB images cannot provide. Leveraging the strengths of vision transformers to effectively capture and exploit these spectral signatures holds promise for advancing the accuracy and precision of HSI in remote sensing classification tasks.

As the field transitions from classical statistical methods to advanced deep learning architectures, a new dimension in HSI classification is emerging. These deep models, capable of learning representations at multiple levels of abstraction, promise to unearth complex patterns within hyperspectral data, potentially surpassing traditional techniques.

Spectral Feature-Based Methods and Spatial–Spectral Feature-Based Methods

Spectral feature-based approaches classify hyperspectral images (HSIs) by analyzing each spectral pixel vector individually. However, this method has limitations as it overlooks the spatial context of the pixels. Spatial–spectral feature-based methods on the other hand, consider both the spectral and spatial characteristics of HSIs in a more integrated manner. These methods involve using a patch that includes the target pixel and its neighboring pixels, instead of just the individual pixel, to extract spatial–spectral features. Among these methods, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are particularly prominent, having shown significant effectiveness in HSI classification. Despite the success of CNN-based models in classifying HSIs, they are not without issues. The CNN’s receptive field is limited by the small size of its convolutional kernels, such as 3×3 or 5×5, which makes it challenging to model the long-range dependencies and global information in HSIs. Additionally, the complexity of convolution operations makes it difficult to emphasize the varying importance of different spectral features.

When comparing spectral feature-based methods with spatial–spectral feature-based methods in hyperspectral image (HSI) classification, each has distinct advantages and applications. Spectral feature-based methods are valued for their simplicity and efficiency, especially effective in scenarios where unique spectral signatures are key, such as in material identification or pollution monitoring. They require less computational power, making them suitable for resource-limited applications. Alternatively, spatial–spectral feature-based methods offer a more comprehensive approach by integrating both spectral and spatial information, leading to higher accuracy in complex scenes. This makes them ideal for detailed land cover classification, urban planning, and military surveillance where spatial context is crucial. Among spatial–spectral methods, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) stand out for their advanced feature extraction capabilities and adaptability, making them useful in a variety of applications, from automatic target recognition to medical imaging. Although, they face challenges such as the need for large datasets and difficulties in capturing long-range spatial dependencies. While spectral methods are efficient and effective in specific contexts, spatial–spectral methods, particularly those using CNNs, offer greater versatility and accuracy at the cost of increased computational complexity.

Hyperspectral Image Classification

In the landscape of hyperspectral image (HSI) classification, a breadth of methodologies has been explored. Foundational techniques such as the k-nearest neighbor and Bayesian classifiers laid the groundwork for statistical approaches to HSI classification. Techniques aimed at class prediction, like multinomial logistic regression, and the support vector machine (SVM) framework, have been instrumental due to their robustness in high-dimensional spaces. Alongside these classifiers, dimensionality reduction techniques, notably principal component analysis (PCA), independent component analysis (ICA), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA), have been pivotal in distilling relevant spectral information from the vast data channels inherent in HSIs.

Despite the efficacy of these methods in spectral analysis, they have often underutilized the spatial information that is equally critical in HSIs. Spatial correlations among pixels carry significant information about the structure and distribution of the materials imaged. To tap into this spatial richness, the use of mathematical morphological operations, such as morphological profiles and their extended versions, have been developed, enriching the feature space with spatial context.

Advanced techniques have also been employed to harness the spatial-spectral synergy more effectively. For instance, approaches that create kernels based on adjacent superpixels or utilize hypergraphs for feature extraction acknowledge the inter-pixel relationships and the non-linear distribution of HSI data. These methods have aimed to achieve a more holistic analysis by integrating spatial contiguity with spectral data, leading to enhanced classification accuracy.

However, there exists a significant opportunity in the realm of deep learning, which has not yet been fully explored in these classical methods. Deep learning architectures, particularly those utilizing layers to hierarchically extract features, could offer a new dimension to HSI classification. By learning representations at multiple levels of abstraction, deep models have the potential to unearth intricate patterns in both the spectral and spatial domains. Such models could extend beyond the capabilities of traditional machine learning techniques, offering a transformative approach to HSI classification that leverages the depth and complexity of hyperspectral data to its fullest extent.

Datasets

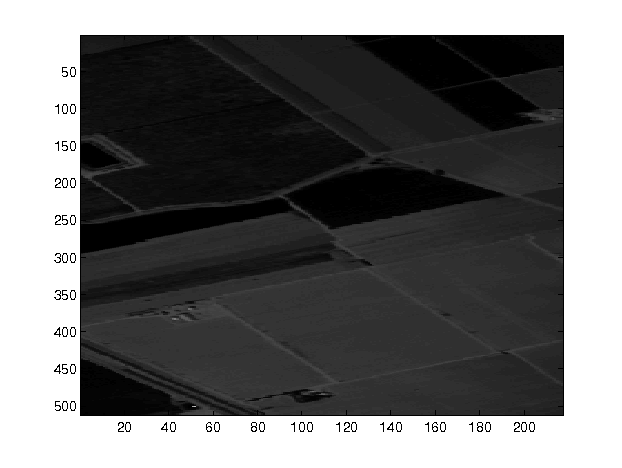

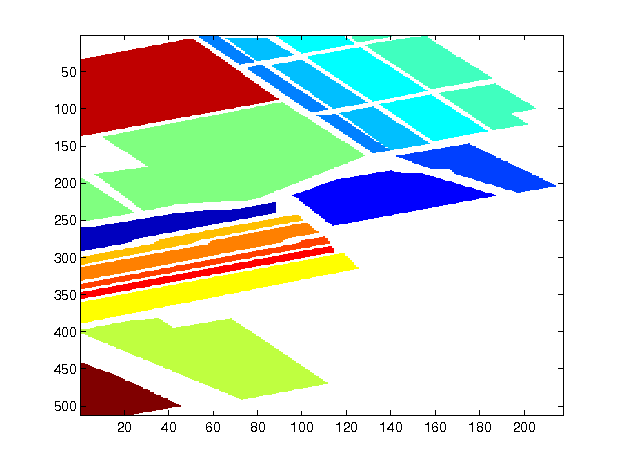

Salinas Dataset:

The Salinas dataset was captured in 1998 by the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) sensor. It includes a spectrum of 224 bands, spanning wavelengths from 400 to 2500 nanometers. For the purposes of analysis, the dataset has been refined to 204 bands, excluding bands affected by water absorption. The Salinas scene measures 512 pixels in height and 217 pixels in width, offering a detailed view of the area. In total, it consists of 54,129 labeled samples, which are categorized into 16 distinct classes, each representing a unique object or feature on the ground.

Pavia University Dataset:

Captured in 2001 using the Reflective Optics System Imaging Spectrometer (ROSIS), the Pavia University dataset originally comprised 115 spectral bands in the 380 to 860 nanometer range. After removing bands with noise interference, 103 bands remain for research analysis. The spatial dimensions of this dataset are notably expansive, with a height of 610 pixels and a width of 340 pixels. The dataset is rich in diversity, encompassing a total of 42,776 labeled samples across 9 different land cover categories. Each category represents a distinct type of terrain or man-made structure within the university area.

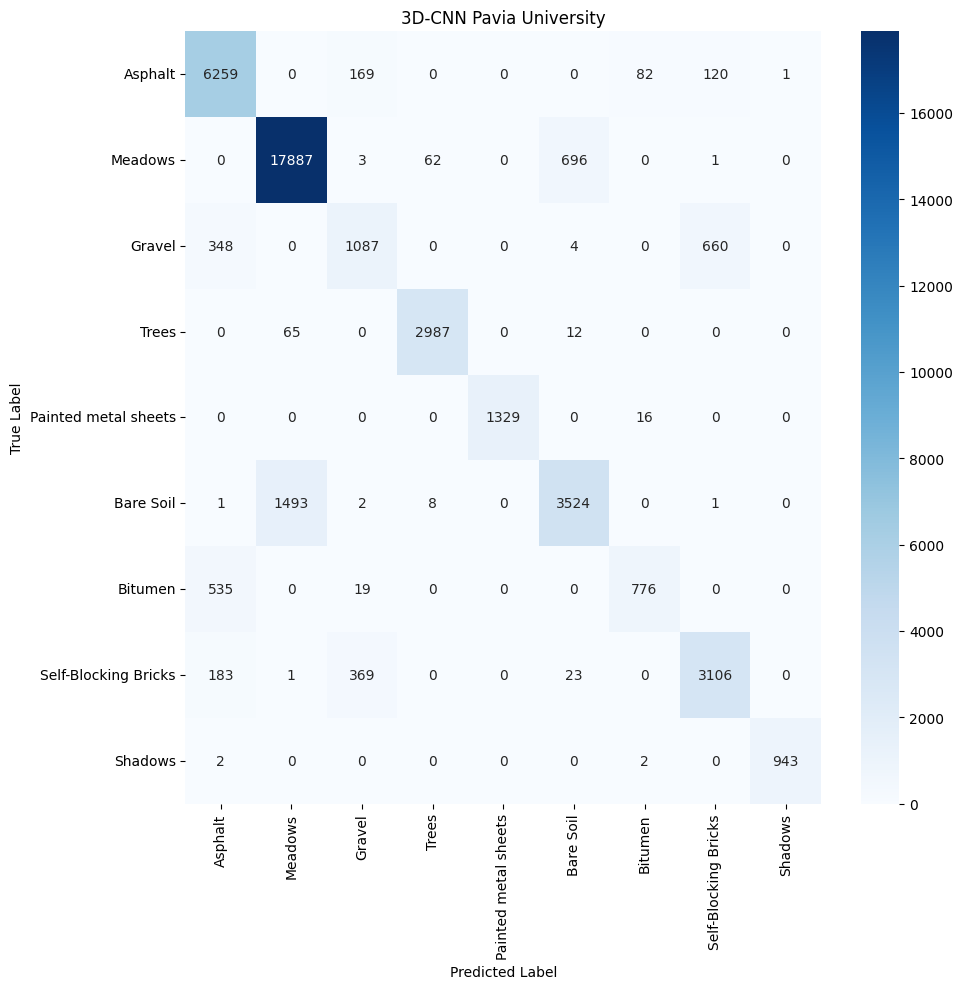

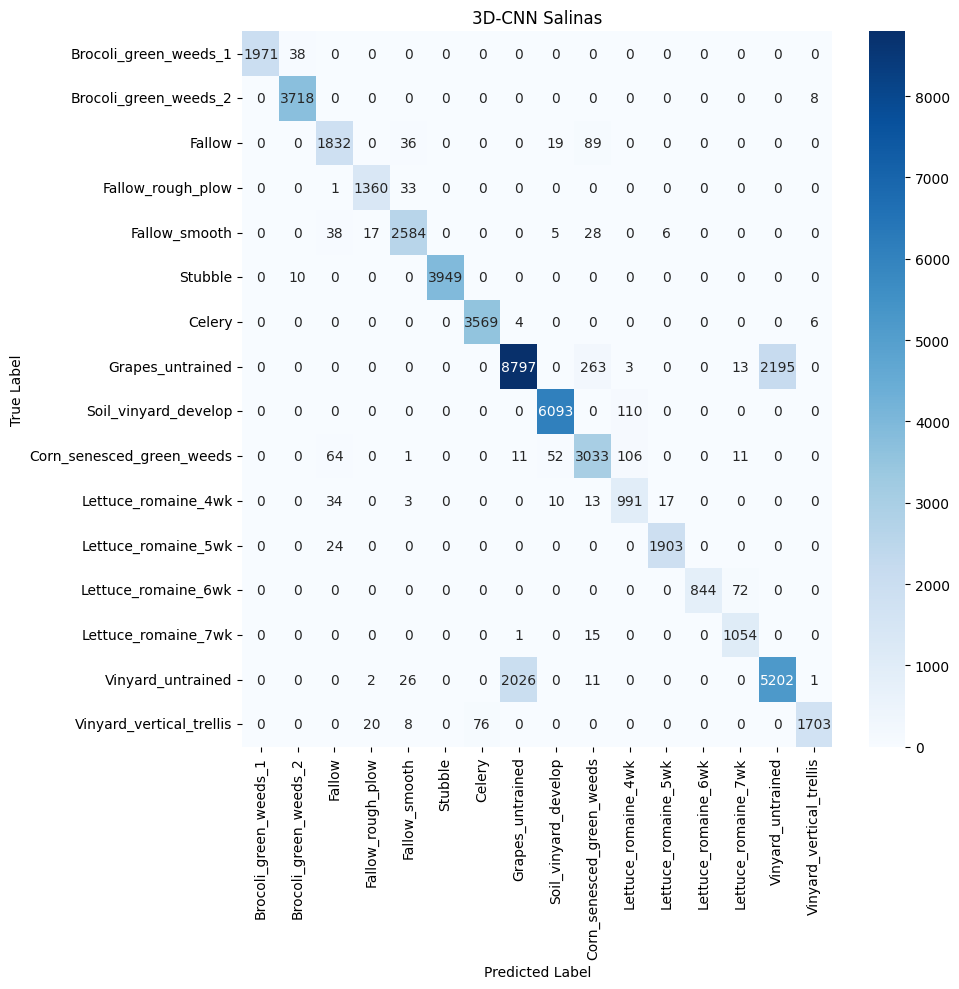

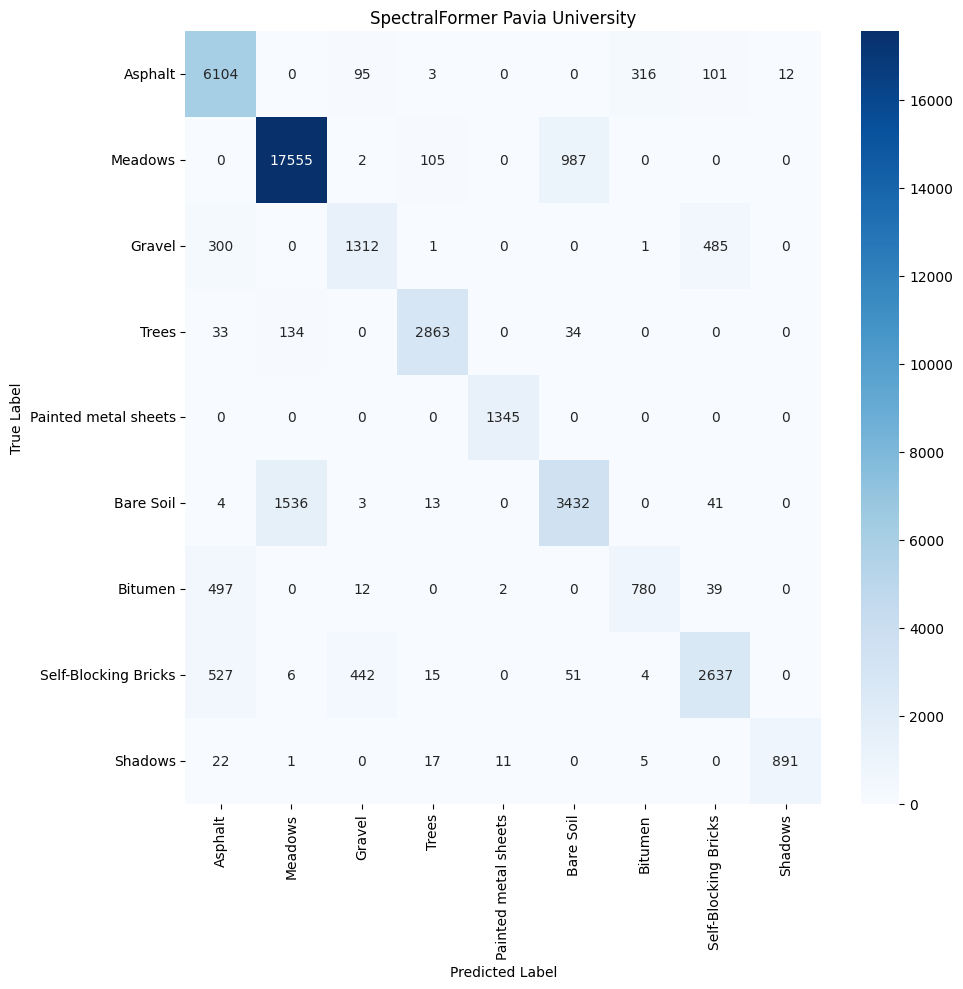

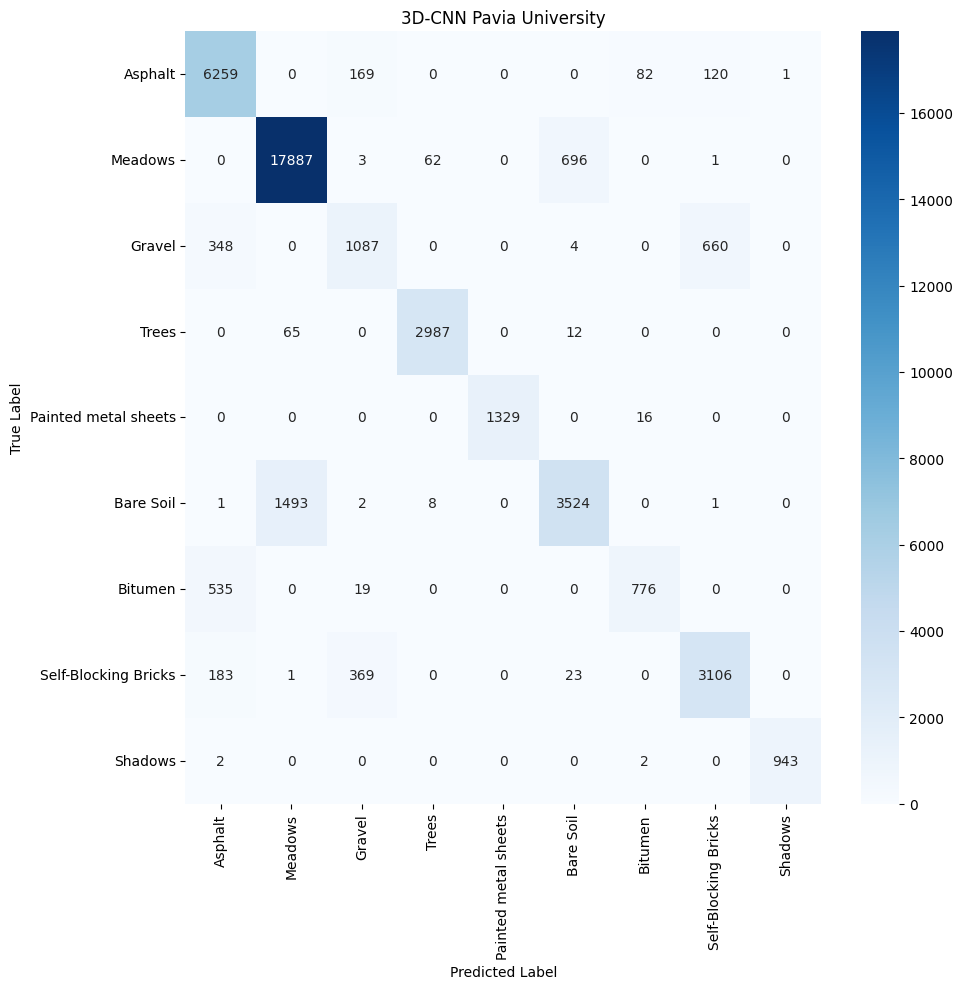

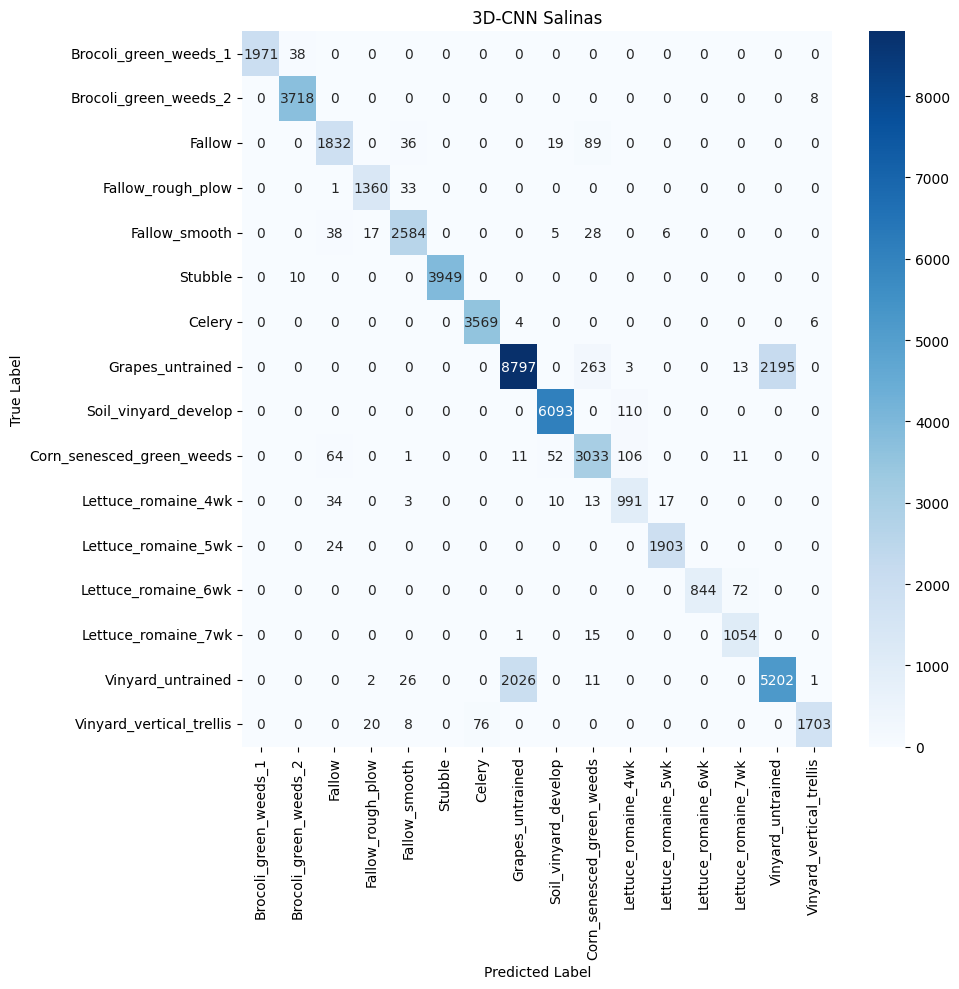

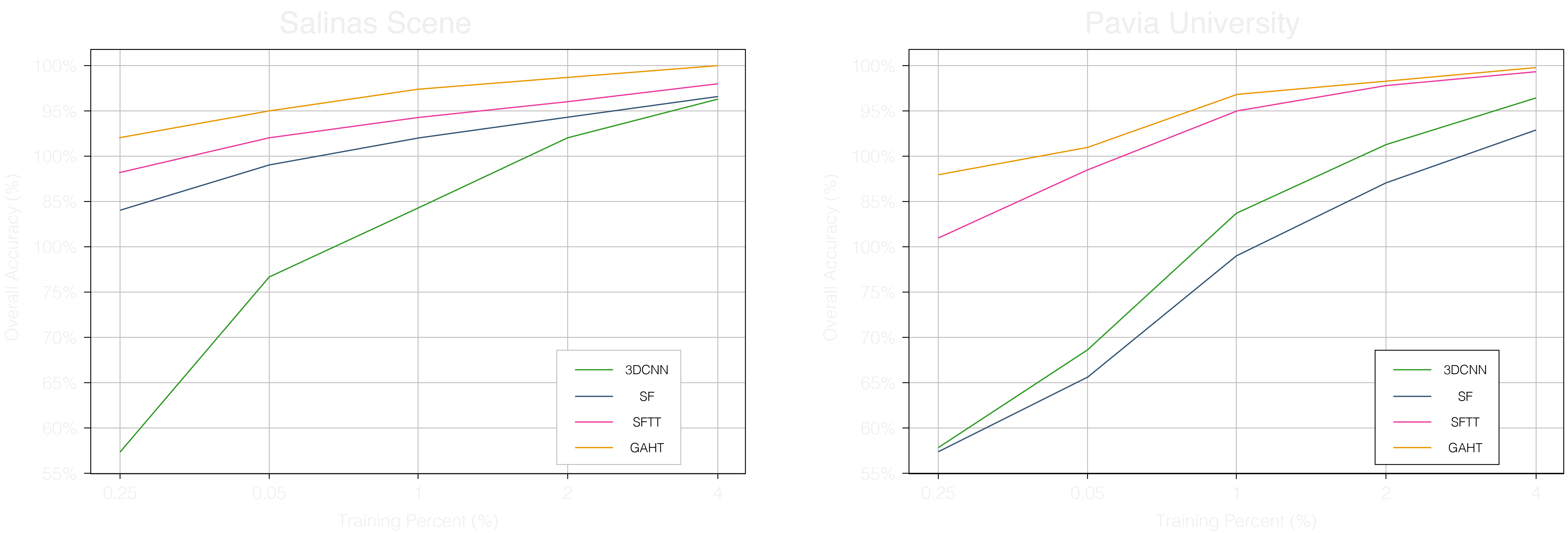

Utilizing these datasets, an analysis is performed on four different models to understand what features are being captured. The first two models, 3DCNN and SpectralFormer, are based on the convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture. The third model, Spectral–Spatial Feature Tokenization Transformer (SSFTT), is a transformer-based model that utilizes a novel tokenization technique to extract spatial-spectral features. The fourth model, Group-Aware Hierarchical Transformer (GAHT), is a transformer-based model that incorporates a multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism to capture global effective spatial-spectral features. The models are evaluated based on their ability to accurately classify the hyperspectral data, with a focus on their capacity to discern and classify diverse land cover types. The key metrics for this assessment include accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1 score extracted from confusion matrices. The models should accurately identify and categorize ecological features from high-resolution imagery.

Three-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (3DCNN)

The 3DCNN

The 3DCNN model demonstrates a capacity for learning and refining its spatial feature extraction processes as evidenced by the increase in overall accuracy with more training data. This underscores its potential in addressing complex classification tasks in remote sensing. However, the observed plateau in performance enhancement, despite additional data, points to intrinsic limitations in the architecture’s ability to represent the rich spectral and spatial diversity of remote sensing datasets comprehensively. While the 3DCNN excels in detecting volumetric patterns through its three-dimensional convolutional layers, its sensitivity to fine-grained spectral details—which are often pivotal in distinguishing similar classes—may not be as pronounced. The architectural design, including dilated convolutions and pooling, effectively condenses the spectral dimension and broadens the receptive field. Nonetheless, this same design choice might inadvertently obscure subtle yet critical spectral information, complicating the differentiation of classes that share close spatial characteristics.

The strengths lie in its ability to process spatial information, which is beneficial for datasets like Pavia University with its urban structures. Yet, its performance on the Salinas dataset, which requires more distinct spectral discrimination, highlights the challenges 3DCNN faces with complex spectral information. To improve its classification performance, especially in spectrally complex environments, integrating spectral-focused techniques or hybrid models that combine 3D spatial processing with enhanced spectral feature improves the model.

SpectralFormer

The SpectralFormer utilizes a Transformer-based architecture with Cross-layer Adaptive Fusion (CAF)

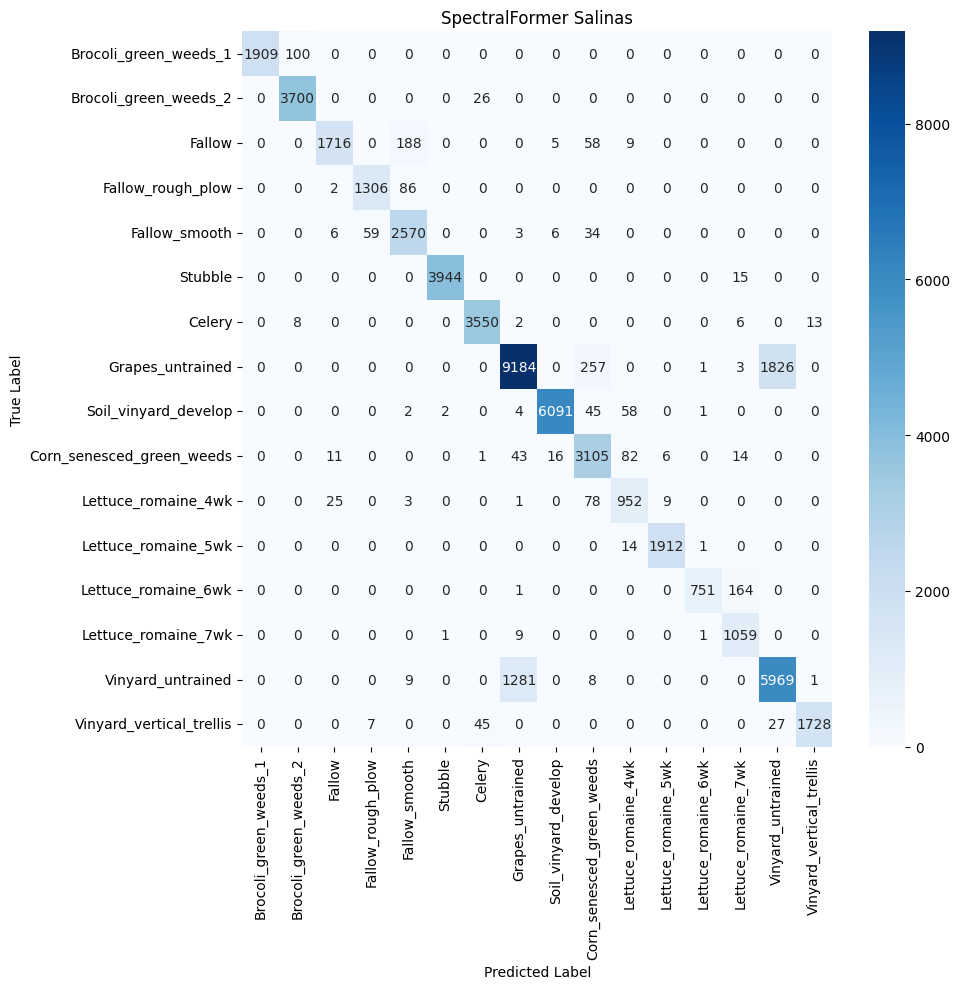

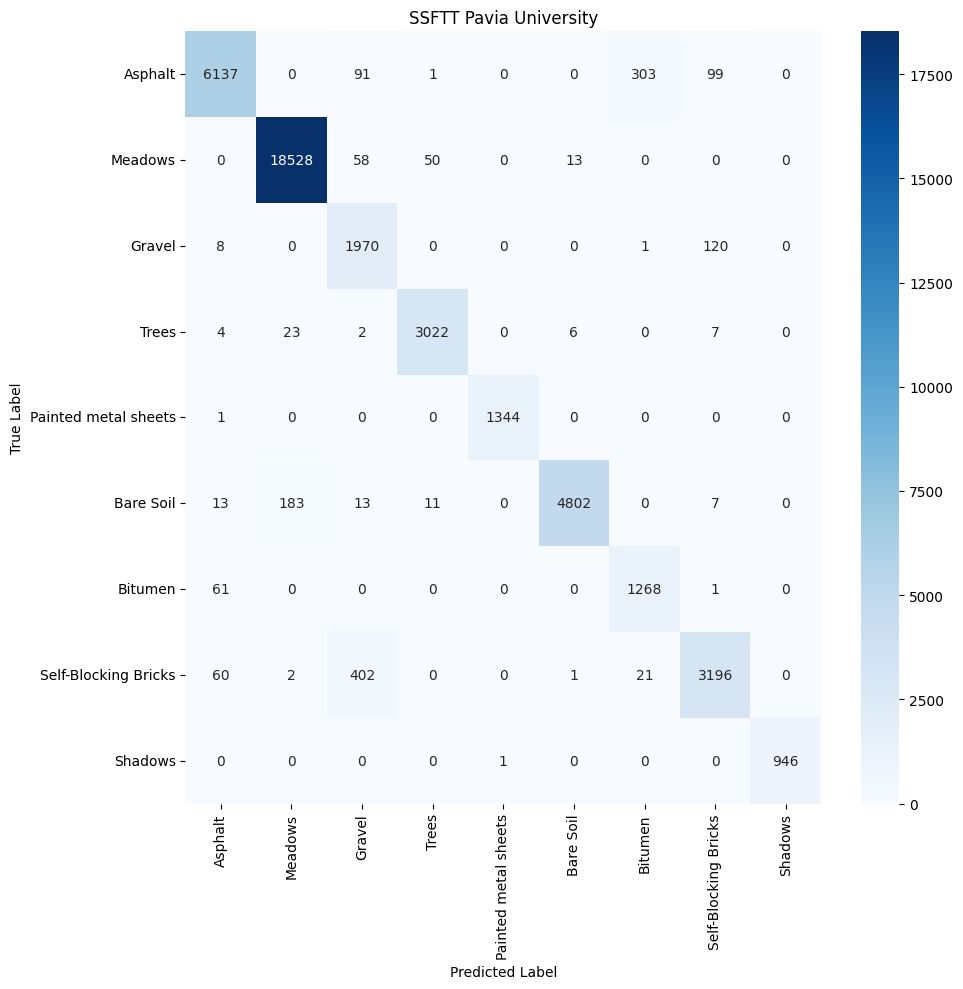

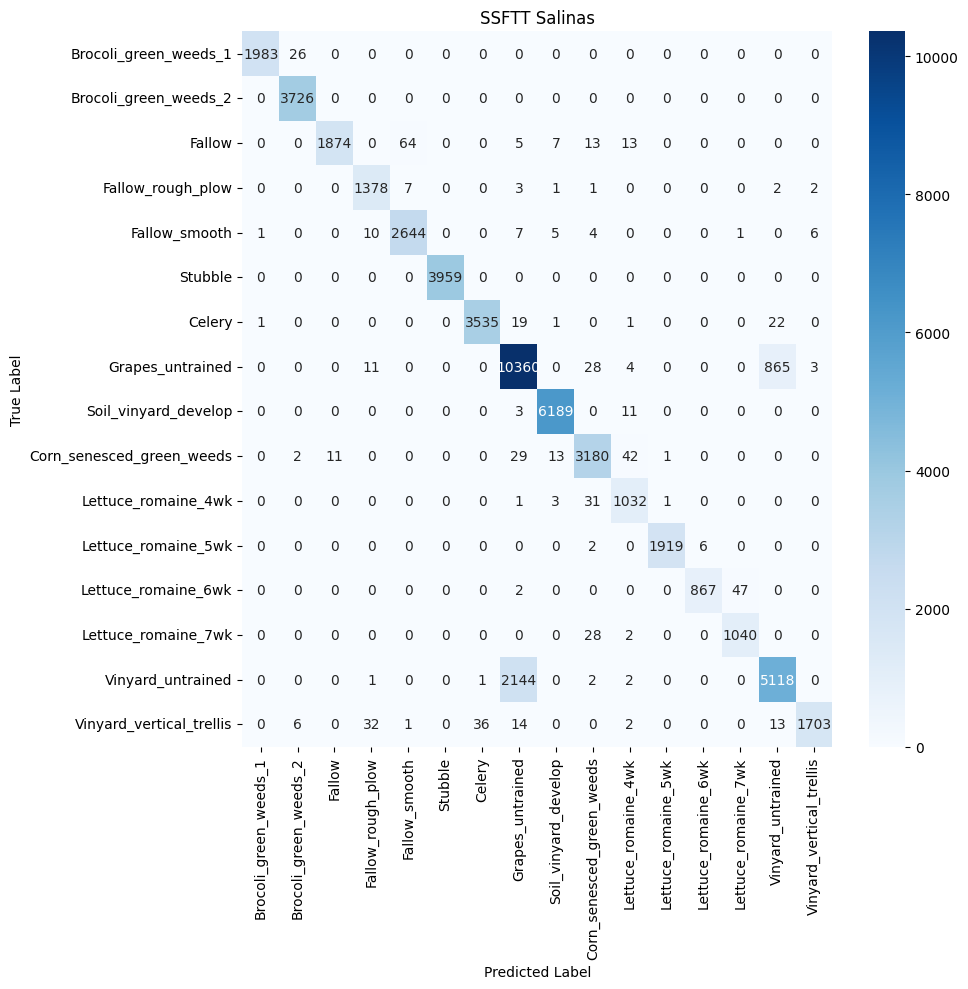

Both datasets indicate that SpectralFormer performs well with certain classes that have distinct spectral characteristics, as seen with ‘Asphalt’ and ‘Meadows’ in Pavia University and ‘Grapes_untrained’ and ‘Soil_vinyard_develop’ in Salinas. However, the model shows some limitations in distinguishing between classes with similar spectral profiles or when spectral features are subtle, such as ‘Bare Soil’ and ‘Bitumen’ in Pavia University, and ‘Brocoli_green_weeds_1’ and ‘Brocoli_green_weeds_2’ in Salinas. This due to the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism which, while adept at identifying dominant spectral patterns, doesn’t capture the finer differences between closely resembling classes.

The SpectralFormer’s moderate class separation reflects its challenge in spatial-spectral feature discrimination. Although its CAF module is designed to enhance feature representation by fusing information across layers, the results suggest there might be room for improvement in its capability to discern overlapping spectral and spatial features. This is particularly evident in the clustering of urban landscape classes in the Pavia University dataset, where the architectural and natural features present similar spectral profiles but differ in their spatial arrangement. While the SpectralFormer shows promise in processing hyperspectral data with complex spectral signatures, its performance might be enhanced by further tuning to address the subtle differences between similar classes. Advancements could include integrating more specialized attention mechanisms or layer fusion techniques to refine its spatial-spectral feature extraction. Additionally, employing domain-specific augmentations or preprocessing steps to emphasize the differences between challenging classes could further bolster its discriminative power.

Spectral–Spatial Feature Tokenization Transformer

The Spectral–Spatial Feature Tokenization Transformer (SSFTT)

Group-Aware Hierarchical Transformer (GAHT)

The GAHT

The Grouped Pixel Embedding (GPE) module, an integral part of the Group-Aware Hierarchical Transformer (GAHT), is designed to enhance local relationships within Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) spectral channels. It operates by dividing the channels of feature maps into non-overlapping subchannels, focusing on local relationships within the spatial-spectral features of HSIs. This division is crucial for capturing fine-grained details and local variations within hyperspectral data. Additionally, the GPE module emphasizes these local relationships in the spectral domain, complementing the global dependencies captured by the multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism. This dual focus ensures that the model effectively captures both local and global spatial-spectral context, resulting in a more comprehensive feature representation. Furthermore, by extracting spatial-spectral features from these non-overlapping subchannels, the GPE module aids in capturing the unique characteristics of grouped features of feature maps. This leads to a more effective exploration of the spatial-spectral information present in hyperspectral data, ultimately enhancing classification accuracy.

Analyzing GAHT features from the Pavia University and Salinas Scene datasets reveal the discriminative power of the feature representations learned by the model. In the Pavia University dataset, the emergence of distinct clusters for classes such as Trees, Meadows, Asphalt, and Self-Blocking Bricks suggests that the model is highly effective at distinguishing these features within the hyperspectral data. However, the observed overlap among classes like Shadows, Gravel, and Painted Metal Sheets might indicate either inherent similarities in their spectral signatures or an insufficient spatial resolution that leads to mixed pixels. Such overlap, while minor, points to the complex nature of hyperspectral imaging where even high-performing models like the one used may encounter challenges in completely separating all material types.

Conclusions

The spatial and spectral complexity of a dataset significantly influences the model’s feature extraction capabilities. For datasets with a strong spatial component, like Pavia University, models with robust spatial feature extraction capabilities, such as 3DCNNs, can perform well. However, for datasets with subtle spectral differences and a wide spectral range, like Salinas, models that can capture fine-grained spectral information, such as GAHT and SpectralFormer, are more advantageous and show the potential of Transformers in hyperspectral remote sensing.

Models that can adeptly handle the dataset’s complexity show tighter and more distinct clusters. It also becomes apparent that no single model outperforms the others across all scenarios; their effectiveness is context-dependent, based on the inherent characteristics of the dataset being analyzed. This suggests that a hybrid approach or ensemble models that combine spatial and spectral feature extraction strengths may be beneficial for complex datasets that present both spatial and spectral challenges. Interpreting hyperspectral imagery through deep learning unveils a landscape where every detail matters. Exploring different models – from the volumetric views of 3DCNN to the intricate layers of SpectralFormer, and from the novel perspectives of SSFTT to the group-focused insights of GAHT – showcases a diverse toolkit for dissecting the complex tapestry of land and life captured from above. The spectral and spatial richness of hyperspectral data beckons for a nuanced approach; models like GAHT and SpectralFormer excel, particularly when fine-grained spectral distinctions are key.

However, no single model claims universal supremacy. The choice of model is guided by the unique spectral and spatial narratives of datasets becoming more and more available. Findings hint at a future where hybrid models will be able to uncover and analyze unique patterns in landscapes. Combining the spatial strength of models like 3DCNN with the spectral sensitivity of transformers could forge analytical power, capable of capturing the subtlest changes in the environment. As we stand at the crossroads of innovation and discovery, the potential of transformers in remote sensing invites us to reimagine the boundaries of what we can see and understand.