Understanding Limitations of Vision-Language Models

Why are vision-language models important?

The emergence of joint vision-language models such as Contrastive-Language Image Pretraining (CLIP) [1] from OpenAI, and GAIA-1 [2] from Wayve AI have had critical implications in computer vision, robotics, generative AI, self-driving, and more. The key idea of these large foundation models is that they learn meaningful data representations of labeled (text, image) pairs. Once trained, these learned representations are sufficiently versatile and can directly be deployed for a broad range of applications. Such transfer learning is referred to as zero shot learning, where the learned representations can directly be used for unseen data in a new task context without any additional training.

How is our work different from previous related work?

Many follow up works have since examined how these large vision-language models perform with respect to various scenarios. Prior works study these effects in the context of transfer learning. Jain et al. looks at how performance is examined with respect to the quality of the dataset and provides examples where the performance can be improved by removing from the source dataset [5]. This can be done by utilizing linear classifiers in a scalable and automatic manner [6]. Santurkar et al. explored the impact of language supervision in vision models, and when the pre-training dataset is sufficiently large and contains relevant captions, the model will outperform other image-only models [4]. Shen et al. investigated CLIP’s advantages in outperforming widely used visual encoders through task-specific fine-tuning and combining with vision-language model pre-training [7]. While the aforementioned literature made valuable contributions in understanding the performance of vision-language models, they do not present a clear understanding of what goes on behind the “black box” of the model’s behavior and performance.

Our study is novel in that we provide a more in-depth, detailed analysis of both the impact of descriptive text (or the lack thereof) in vision-language models, in conjunction with the subtleties of dataset biases. We want to clearly visualize these variables’ impacts on model behavior and provide an explanation for such results. We specifically propose a (toy) expansion of prior work on understanding the role of text description [4]. Prior work claims that text descriptions with low variability will ensure that transferred features from CLIP models will outperform image only models. In our work, we will then examine how more descriptive text labels can help overcome biases in dataset and address domain shift.

How are these models trained?

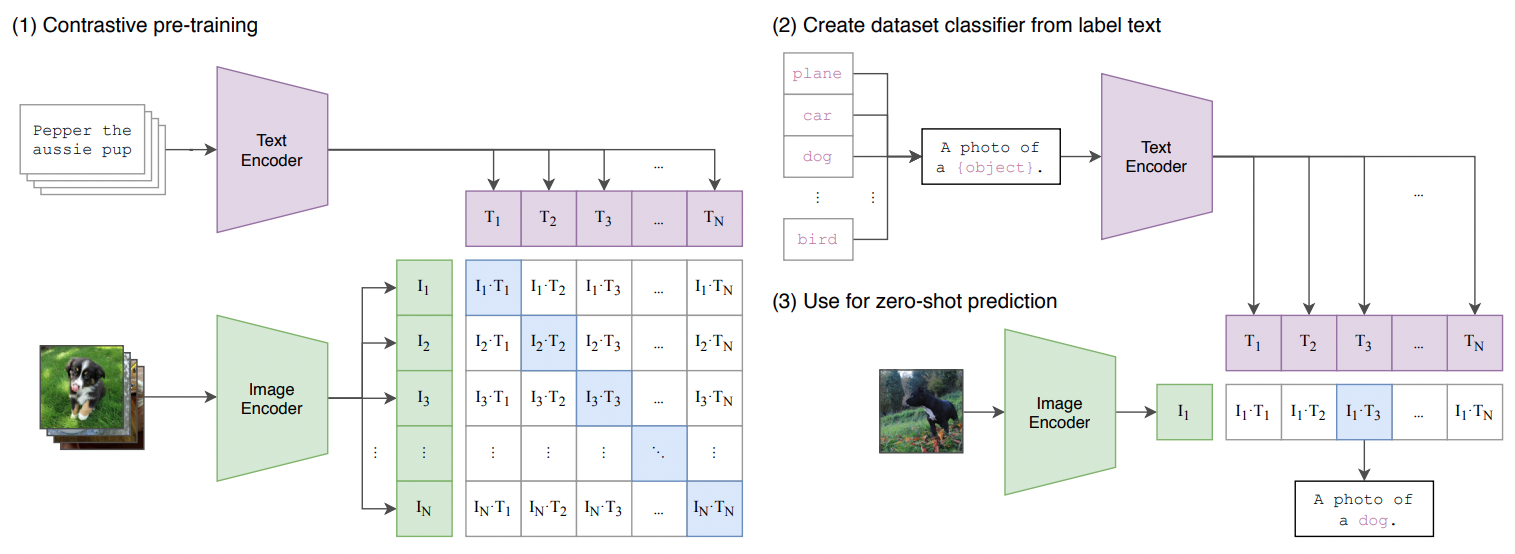

CLIP and GAIA are based on transformer architectures [3], which were originally developed for natural language processing and later adopted for computer vision as well. Two separate encoders, a text encoder and an image encoder, separately transform input data from their respective data modality into feature vectors. In aligning images and text in feature space, CLIP and GAIA are able to learn semantically meaningful and robust representations that are useful for several downstream applications. These models perform this embedding space alignment in different ways. CLIP performs training by predicting which image features correspond to which text embeddings in a batch of (image, text) pairs. GAIA is trained in an autoregressive manner, predicting the next token, given past image, text, and action states. GAIA is reported to have ~9 billion parameters and CLIP is reported to have ~63 million parameters. The differences between these two architectures are also related to the type of input data that is being analyzed. While CLIP operates on single images, GAIA is meant to be used for self-driving, meaning that it operates on videos rather than images. As a result, GAIA requires some notion of temporal consistency, which is why autoregression is a good architecture, and more parameters (since video data is more complex than image data). In this study, we will primarily focus on the CLIP architecture (shown below for convenience).

Figure 1. CLIP Architecture, a commonly used vision-language model [1]. (We apologize for blurring, couldn’t figure out how to get rid of it).

Could the dataset play a role in training?

The nature of the training process of CLIP models introduces questions about how robust the training procedure would be. The training relies on (image, text) pairs, but a single text phrase is not a unique description of an image, and a single text description can be used to describe many different scenes. This one-to-many mapping problem introduces questions about what the optimal text description of a given image should be, or if that optimal description even exists. Santurkar et al. [4] looks at how vision-language models such as CLIP and Simple framework for Contrastive Learning of visual Representations (SimCLR) exhibit different performance based on whether they are trained with or without captions and only images. We were inspired by the study’s suggestion that the descriptiveness of the dataset captions can directly influence how well the CLIP models transfer.

A more interesting question, that we answer in this blog post, is could having more descriptive text descriptions allow these large foundation models to mitigate or overcome dataset bias?

To study this question, we consider a toy example with dogs and camels in the classic domain adaptation problem. In this context, we answer the following question:

Can more descriptive text labels enable better domain adaptation in vision-language models with biased datasets?

Domain adaptation is a problem in transfer learning where we want to have a model be able to learn the model in one context, and then generalize to another context. In other words, given a source domain that the model is trained on, domain adaptation is the problem of having high model performance in the target domain. In the dog vs. camel example, the domain adaptation problem occurs when we are used to seeing dogs and camels in certain contexts. For example, we generally expect to see camels in the desert and dogs in suburban environments (e.g. on the lawn, inside the house). If a model is trained to see such examples, then is suddenly shown a camel inside a house in Cambridge, the model has a strong chance of failure. Performance failure under domain shift is indicative that the model failed to disentangle background features from the camel itself. We will study whether descriptive text labels can enhance domain adaptation ability of current transformer-based foundation models.

Understanding role of text labels in CLIP, GAIA

Due to the large model size, invisible datasets, and large number of GPU hours needed to train CLIP and GAIA, we perform an analysis in a toy setup using the domain adaptation problem we described above. Our goal is to align image and text features, and then visualize the embeddings corresponding to different image classes.

Each of the four experiments determine 1) how the models respond to dataset bias, and 2) how important the addition of descriptive text labels are in improving performance using a trade-off combination of the variables. We aim to measure and visualize the extent to which the caption aids in overcoming biases in training data.

Architecture

Our architecture is shown below. We have two separate transformer architectures: an image encoder and a text encoder. The output of each of these encoders is mapped to an image and text embedding, then L2-normalized. We then compute the cosine similarity of the two embeddings and use the similarity and compute a binary cross entropy loss. Note that, unlike CLIP, we do not compute similarity across all samples within a batch. We only compute cosine similarity for a sample (image, text) pair.

Dataset

Image Generation. We generated our own dataset using DALL-E 2. The total size of the training dataset is 196 images, with (1) 48 images of horses on grass, (2) 48 images of horses in the desert, (3) 48 images of camels in the desert, and (4) 48 images of camels on grass. Note that the DALL-E generated images are used for academic purposes, and are not intended for any commercial use, as required by DALL-E terms and conditions.

Text Labels. We had two cases: a descriptive label and an undescriptive label. In the descriptive label case, we used the following labels for each of the four cases above (1) “horse on the grass”, (2) “horse in the desert”, (3) “a camel in the desert”, (4) “camel on the grass”. In the undescriptive label case, we just used the labels (1) “horse”, (2) “horse”, (3) “camel”, (4) “camel”.

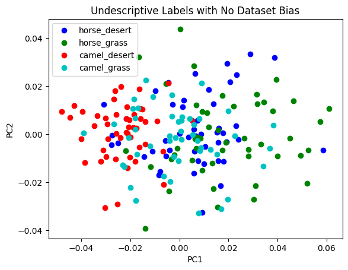

Experiment 1: No Dataset Bias, Undescriptive Text Labels

Description: In the first experiment, we first baseline our text and images encoders ability to perform classification of camels and horses in the case when there is no dataset bias. We use all 196 images with undescriptive labels, so that there is an even split between all four cases (each case comprises ¼ of the dataset). The goal is to assess how well the model can learn and generalize across different classes, and provides the basis for the models’ inherent capabilities and performance without impact from external factors.

Results: We performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the feature vectors of our output from the image encoder and the text encoder in order to visualize more similar labels being mapped closer to each other. We notice that camels in desert and camels in grass are closer together in the feature space, while horses in desert and horses in grass are closer together. There is some overlap between camels in grass and horses in deserts, indicating some confusion with the context of the scene. That said, there is a very clear distinction between camels in the desert and horses in the grass, implying that the model is clearly aware that they are very different classes. The overall separation is rather decent when there is no dataset bias.

Figure 2. Vague separation in different environments with less descriptive labels.

Experiment 2: No Dataset Bias, Descriptive Text Labels

Description: In the second experiment, we keep the dataset unbiased, but add descriptive labels.

Results: In the plot below, we can see that using descriptive labels slightly improves the separation between classes in the unbiased dataset case. Specifically note the strong separation between red (camels in desert) and green (horses in grass). These two cases are easiest to distinguish, as is reflected in the scattered plot below. Interestingly, when we use descriptive text, the labels are getting bunched together based on context. In particular, horses and camels in the desert are being placed close together, while horses and camels in the grass are being placed close together. This is likely because the model is learning to use the context as a way to separate classes as well. There is still a general progression from red (camels in desert) → blue (horses in desert) → cyan (camels in grass) → green (horses in grass), suggesting some semantic smoothness in feature space. The transition between blue and cyan is rather abrupt though.

Figure 3. Improvements in class separation with more descriptive labels.

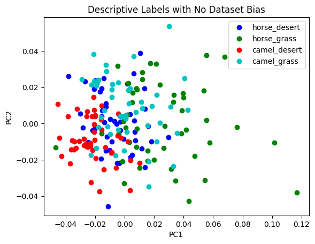

Experiment 3: Dataset Bias, Undescriptive Text Labels

Description: In the third experiment, we begin to investigate the role of dataset bias. The goal is to build on the results from the first experiment, reproducing a common aforementioned problem of over- or under-representation in datasets. We look at how the model responds to dataset bias and whether its performance can still stay the same, regardless of how the images are distributed in classes. Dataset bias is defined by the percentage of minority samples that we remove (minority samples are horses in desert and camels in grass). For example, we originally used 48 images of horses in the desert. 25% bias is defined as using only 12 images of horses in the desert.

Results: These results will be jointly explained with experiment 4.

Experiment 4: Dataset Bias, Descriptive Text Labels

Description: In the fourth experiment, we dive deeper into the impact of dataset bias that we began exploring in the second experiment, and question whether performance will be improved when the provided text labels are more descriptive. This directly answers the question of how impactful descriptive text is in vision-language models, in addition to whether they can help overcome dataset bias.

Results: Surprisingly, when the dataset is more biased, we find that the separation between classes is better. We believe this to be true because the model is able to identify clear separation between horses and camels based on the context alone. As a result, it is easily able to separate red and green classes as the bias increases. We notice that the minority classes (horses in desert and camels in grass) also spread out in latent space as the dataset is biased. When using descriptive labels, we notice that the blue points (horses in the desert) are able to separate themselves more from other clusters than in the undescriptive case, indicating some success with descriptive labels in the event of dataset bias. Overall, across all cases, the model generally has an easy time separating camels in the desert, which is likely due to the distinctness of the background and the object.

Figure 4. More biased dataset can show more separation between classes.

Limitations and Potential Confounding Parameters

There are several possible confounding parameters that may have impacted our results beyond the variables that we were looking at. They include the following:

Dataset

Generating the dataset: Because we used DALL-E to generate our dataset, the limitations of DALL-E itself can carry over to our performance. The inherent diversity of the data that DALL-E uses to train would directly impact our results, as well as the hyperparameters that were modified in training DALL-E. DALL-E could also have a specific image aesthetic that are different from real photography.

Size: Model performance can also be impacted by a limited dataset. We trained and validated our model on 196 images, which is not a large dataset. The confounding variable here would be the complexity of the images, where there may be less images with less clear distinctions of “horses in the grass” or “camels in the desert”. Furthermore, there are different breeds, sizes, colors, and shapes of horses and camels that may not have been fully explored due to less room for them.

Composition sensitivity: Literature review has shown that the model’s performance can be impacted by quality in addition to the quantity of the data [5]. Recent evidence has proved that removing data from a dataset can aid in transfer learning and improve downstream effectiveness. While we did not run experiments in identifying what specific composition and characteristics of the data should be removed, the analysis would have impacted our results.

Model

Computational resources: Because we were restricted by GPU resources, we chose to use a smaller dataset and small self-trained Transformer architectures. We were also unable to train for more epochs, restricting having a more complex model architecture that could’ve lowered model performance. We found that increasing the batch size or increasing the number of layers lead our model to run out of computational power and continually crash.

Tuning hyperparameters: Batch size, learning rate, number of layers, optimization models, and other factors could also limit the exploration of optimal configurations and affect overall performance. For example, a higher learning rate in a model could converge faster and show higher performance, when in reality, it is not an accurate reflection of the model. Overfitting and different regularization parameters can also lead to over- or under-fitting.

Conclusions

Our toy problem gives some intuition into the idea that the descriptiveness of the label can affect the clustering profile of different datasets. Note that because our experiments were done in smaller settings, we cannot make any claims with respect to scaling up to large amounts of data, compute, and model size. That said, when adding description of the context of the images (i.e. desert vs. grass), we noticed that the points in feature space began to cluster first based on context, then based on the animal type (camel vs. horse). We also noticed that under dataset bias, the majority groups (horses in grass and camels in desert) begin to have better clustering separation. However, the minority group performance decreased, which suggests the importance of accounting for dataset bias in machine learning algorithms. In our experiments, we partially found more descriptive labels to help mitigate these negative effects, but mitigating these effects more reliably is an ongoing research direction.

References

-

Radford et al., “Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision”, ICML 2021

-

Hu et al., “GAIA-1: A Generative World Model for Autonomous Driving”, arXiv 2023

-

Vaswani et al. “Attention Is All You Need”, NeurIPS 2017

-

Santurkar et al., “Is a Caption Worth a Thousand Images? A Controlled Study for Representation Learning”, CVPR 2022

-

Jain et al., “A Data-Based Perspective on Transfer Learning”, CVPR 2023

-

Jain et al, “Distilling Model Failures as Directions in Latent Space”, ICLR 2023

-

Shen et al. “How Much Can CLIP Benefit Vision-and-Language Tasks?”, arXiv 2021